By Jay Landers

Amid the tech industry boom of the past several years, residential rents have soared in the San Francisco Bay Area, increasing the number of an already-high homeless population. Looking to address this critical problem as quickly as possible, California’s San Mateo County turned to modular construction to speed up the delivery of what is called a “navigation center.” This is a relatively new alternative to traditional shelters that provides temporary, independent housing and assistance to residents with the goal of ultimately transitioning them to permanent housing.

Comprising 240 sleeping units in prefabricated modules and three larger buildings situated on 2.5 acres in Redwood City, the new San Mateo County Navigation Center is slated to begin operations in March.

Ongoing construction of the project is scheduled to conclude in early March, approximately a year after starting. The modular nature of the project, together with the county’s determination to open the center as soon as possible, helped ensure that the effort would be completed much faster than a comparable facility built using traditional construction methods.

‘Functional zero homelessness’

San Mateo County has set a goal to achieve “functional zero homelessness,” says Sam Lin, the director of the Project Development Unit, which manages new construction for the county. Functional zero homelessness entails having the capacity to provide safe accommodations to every homeless person in the form of emergency shelter, temporary housing, or permanent housing.

The San Mateo County Navigation Center will provide private, independent, temporary housing for up to 260 individuals seeking to transition away from homelessness. Originally developed by the city of San Francisco, the navigation center concept aims “to help homeless folks navigate from living on the streets to permanent housing,” says Charles Bloszies, FAIA, S.E., LEED AP, a principal at the Office of Charles F. Bloszies FAIA. The firm, which specializes in urban infill design primarily in the San Francisco area, is serving as the architect and structural engineer for the San Mateo County Navigation Center, where residents typically will stay 90-120 days before moving into permanent housing.

A different approach

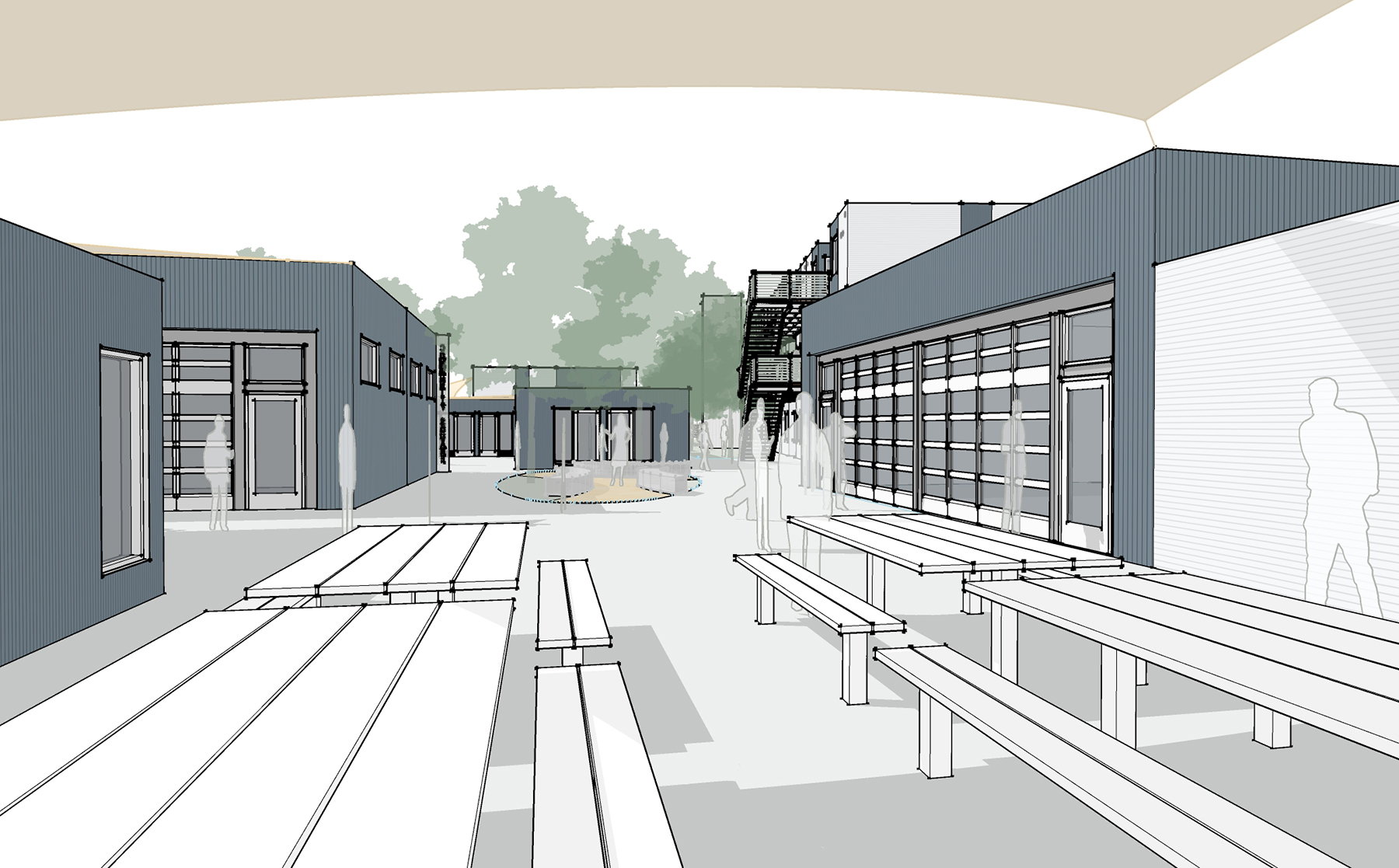

Designed as a campus, the facility consists mainly of 10 ft by 40 ft modules that have two or four sleeping units in each and are arranged in the form of either three-tier, two-tier, or single-story wings radiating out from a central gathering space. Exterior accessways will link the tiered units.

Most of the units have private bathrooms, and all are climate controlled and comply with the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Most units will house a single occupant, but a small number of larger units are available for couples. The three nonmodular buildings, one of which includes a commercial kitchen, are used for gathering, job training, and communal dining.

By offering secure units for individuals, the navigation center resolves three key concerns — privacy, possessions, and pets — that keep some homeless residents from taking advantage of traditional, dormitory-style shelters, Bloszies says. “Navigation centers are a different approach,” he says.

Besides housing and food service, the San Mateo County Navigation Center will provide laundry and storage facilities for residents as well as counseling and dental services. “All of those features really help give these folks the support they need,” Bloszies says.

Compared to a traditional shelter, the navigation center is “more like a home,” Lin says. At the same time, the layout of the campus is intended to promote a sense of community among the residents.

“It's always very healing when you're situated in an environment where people are encouraged to interface with each other,” Lin says. He likens the facility to a “really good village” that enables those staying there “to refresh and restart.”

Making the most of modular construction

Faced with a burgeoning crisis of homelessness, San Mateo County sought to deliver the navigation center in Redwood City as quickly as possible. “Time is of the essence,” Lin says. “This is something that our county leadership definitely wants to tackle and resolve.”

Given the pressing need for rapid solutions, modular construction made the most sense for the project, Lin says. “In a typical time frame, this would take two years,” he says. “But we will finish construction in one year because of the modular concept.”

During the fabrication of the modular components, construction began at the project site, including grading, utility installation, and foundation construction. “The benefit of modular construction is that you can build (the modules) in the factory, in parallel with building on the site,” Bloszies says.

In fact, construction could have been completed even sooner, if not for challenging geotechnical conditions at the site, which is underlain by highly compressible soil known as bay mud. Because of its location in a floodplain, the site also needed to be raised by 3 ft to protect against flooding, Bloszies says.

To account for the anticipated compression of the bay mud, a total of 6 ft of fill had to be added, half of which was surcharge. After three months, the top 3 ft of the added fill was taken away. Had the site not required surcharge, the design and agency approval process likely would have required nine instead of 10 months, Bloszies says, while construction likely would have lasted 10 months instead of a year.

The modules were fabricated by Silver Creek Industries LLC, while project construction is being conducted by the general contractor XL Construction Corp. as part of a design-build contract. BKF Engineers provided civil engineering services; Meyers+ Engineers provided mechanical, electrical, and plumbing performance designs; and CMG Landscape Architecture served as the landscape architect. The navigation center will be operated by LifeMoves, a nonprofit organization that provides housing and related services to homeless people.

Focus on sustainability

Each modular housing unit rests on a concrete slab foundation underlain by a vapor barrier. Besides the housing units themselves, other modular components include the exterior stairs, walkways, and decks. The units are designed to support the decks and walkways, obviating the need to construct separate structures or foundations.

The project is intended to be certified as a Silver facility in keeping with the requirements of the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process overseen by the U.S. Green Building Council. To this end, solar panels on all structures at the site will generate approximately 60% of the project’s estimated total yearly energy requirements, Bloszies says.

To reduce energy use, the project includes “highly efficient” heat pump mechanical systems and water heating systems, Bloszies says. “By combining photovoltaic and efficient mechanical, electrical, plumbing systems, our project will only use one quarter of the yearly energy that a typical baseline project designed to meet national building codes would use,” he says. No gas heating or other gas service is included as part of the project. Landscaping at the site will be irrigated completely by means of recycled wastewater provided by a municipal source.

Funding sources

The overall project has a budget of approximately $57 million, with individual units costing approximately $225,000, Lin says. Units are expected to have a design life of 20-50 years.

Approximately $46 million in funding for the project was provided by the state of California as part of its Homekey program. Overseen by the California Department of Housing and Community Development, Homekey funds efforts to provide housing for homeless individuals throughout the state. Another $5 million was donated by California real estate developer John Sobrato, with the remainder of the project cost covered by federal grants and county funds, Lin says.

This article first appeared in Civil Engineering Online.