The 100-seat theater that architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed and used as part of his 800-acre estate known as Taliesin, near Spring Green, Wisconsin, has been restored and its facilities improved following years of water infiltration, structural damage, and a lack of certain amenities for audiences and performers.

The five-year, roughly $1.1 million dollar project began in 2019 and concluded when Hillside Theater reopened for performances in June with a strengthened structure, a rebuilt stage, new green rooms and other backstage facilities, improved mechanical systems, new accessible bathrooms, a new path to make the entrance more accessible, and other features, explains Ryan Hewson, director of preservation at Taliesin for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

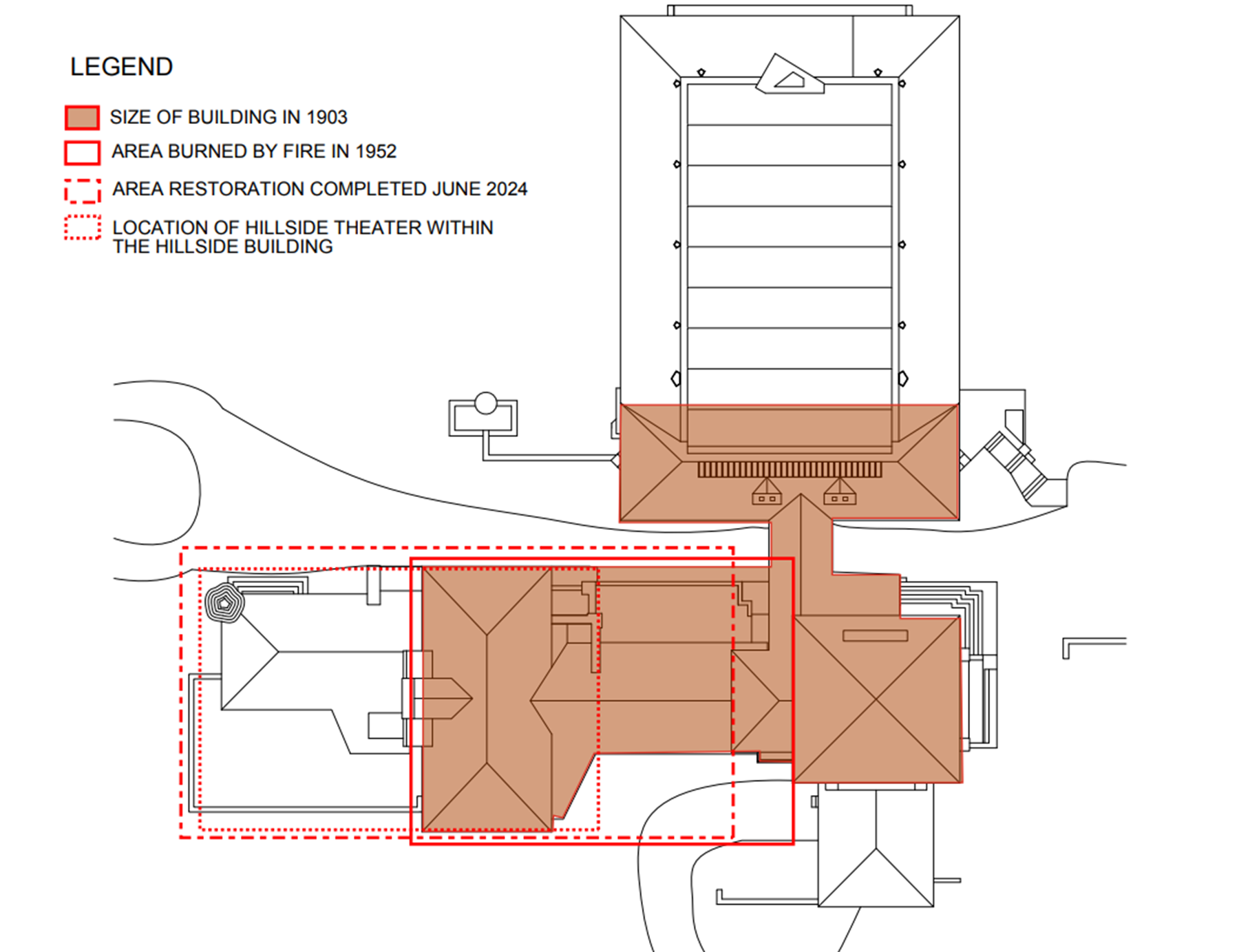

Hewson, who earned his master’s degree in architecture from Taliesin’s School of Architecture, explains that the theater is part of a larger building designed by Wright that originally housed a boarding school run by Wright’s aunts. The space that is now the theater had first served as a gymnasium with a stage and a suspended running track. Over the decades, the school became a drafting studio and the gym became a dedicated performance space with a new entrance foyer. Within the theater, the running track was converted into theater boxes, wooden benches were added as audience seating, and the stage was separated from that audience by an enormous, Wright-designed curtain.

Further reading:

- Visualization unveiled for unbuilt Frank Lloyd Wright tower

- Hands-on experience is key to historic preservation engineering

- New York project lifts landmark theater

Much of the theater was heavily damaged by a fire in 1952, which “led Wright to redesign the theater into what we have now and what we just restored,” Hewson said.

The Wright stuff

The space features numerous traditional Wright touches, including the use of natural materials, such as locally quarried sandstone and locally harvested oak, large windows, and plaster on the walls and ceilings. The entranceway features a relatively low ceiling, just slightly more than 6 feet in height, that leads into a taller foyer to create a sense of “compression and release that sort of pushes you through the door to get you into the larger space where people gather,” Hewson explained.

But while the theater was a beautiful example of Wright’s architectural vision, which the restoration project worked to preserve, the space was also lacking in certain aspects that have now been added or enhanced. For example, the exterior entrance to the theater part of the building and the only bathroom within the building for audience members were difficult to access for people with mobility challenges. The entrance originally featured a set of somewhat uneven limestone stairs that wrap around a large oak tree, while the bathroom had a narrow door and could be reached only by making a 90-degree turn around a stone wall, which was difficult for someone in a wheelchair, notes Paul Kardatzke, LEED AP, AIA, the CEO and lead architect at Jewell Associates Engineers, based in Spring Green. Jewell served as the structural and civil engineer for the restoration work.

Kardatzke, who earned a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the University of Illinois Chicago and a master’s in architecture from Taliesin, explains that access to the building entrance was improved by the construction of an Americans with Disabilities Act-compliant compacted gravel path and ramp that skirt the other side of the oak tree to reach the covered entrance patio. A wider, more accessible opening for the bathroom was created by cutting through the stone wall and installing a steel lintel and steel posts around the new door, “hidden in the stonework or the framing,” Hewson said.

An accessible bathroom for performers was also added in the building’s basement backstage area, which is on the same level as the stage floor, roughly 10 feet below grade, Hewson says. A new, 6-inch-thick concrete slab was also installed backstage, where previously there had been dirt or gravel floors in some areas, notes Kardatzke, who occasionally performed in the theater while an apprentice there. Two new green rooms, where performers relax or get ready, as well as a makeup area with a sink, storage spaces, and a room for new mechanical system equipment were also constructed backstage.

The backstage spaces are directly beneath a dining hall, the floor of which was supported on wooden columns, some of them rotting, or stone pillars, some without footings. To structurally strengthen these spaces, new wood-framed bearing walls were constructed on the new concrete slab and new concrete footings were installed in key locations, Kardatzke says. Wherever possible, the original wooden columns and stone pillars were incorporated into the new construction to preserve Wright’s original designs. In addition, laminated veneer lumber beams were installed alongside some of the original floor joists to support the dining room floor while also preserving the original structural system.

Water falling

To address water infiltration, the ground around the theater – which, as its name implies, was constructed in the side of a hill – was regraded and new high-density polyethylene pipes, up to roughly 18 inches in diameter, were installed to direct water around or safely under the site. A large stone planter on the northern exterior of the building had also been a source of water infiltration into the basement spaces. Measuring roughly 10 feet by 40 feet in plan and approximately 10 feet deep, the planter had been constructed atop a clay subsoil with no waterproofing originally. To correct that problem, the planter was excavated, and two layers of waterproofing barriers were added, along with a French drain that directs water to a new sump where it can be pumped out, Hewson says. Clear stones then filled much of the planter for improved drainage, with about a foot and a half of topsoil at the surface for the vegetation.

Athough the project team had not originally planned to rebuild the theater’s stage, preliminary investigations of the stage “discovered a lot more water damage than expected,” Hewson says. As a result, a new concrete topping slab was poured, and timber studs and joists were installed, along with a plywood subfloor. About 80% of the historical red oak floorboards were then reinstalled, with new floorboards used in just the backstage area that the audience does not see, Hewson says.

The roll roofing over the foyer was also replaced, and a thin concrete roof above the theater – installed following the 1952 fire – had a rubberized membrane added to extend the useful life of the structure, Hewson says. Although the theater does not have a complete climate-control system, new mechanical equipment – including a variable refrigerant flow system – was installed to help extend the annual season for performances. Located in a tourist area that sees few visitors in the winter, the theater was previously limited for use mostly between May and September because of temperature and humidity issues, Hewson says. Now, the season will likely be extended through November.

A livestreaming camera system was also installed, which extends the reach of the theater’s potential audiences from a “100-seat theater to an infinite seat theater!” Hewson said.

Much of the restoration project was funded through the National Park Service’s Save America’s Treasures program. Although additional work is planned in other parts of the Hillside building, Hewson adds, the recently completed efforts have already enhanced the theater for years to come. Perhaps the most powerful feedback the project has received came from a former Wright apprentice, Kelly Oliver, now in his 90s, who was able to attend the reopening of the theater, thanks in part to the new accessibility features. Studying a site he knew quite well, Oliver, who also worked on the theater’s 1952 reconstruction, noted that “it looks like you didn’t do anything” – which in the spirit of restoration and preservation is the highest compliment possible, Hewson feels.