Brian Brenner, P.E., F.ASCE, is a professor of the practice at Tufts University and a principal engineer with Tighe & Bond in Westwood, Massachusetts. His collections of essays, Don’t Throw This Away!, Bridginess, and Too Much Information, published by ASCE Press, are available in the ASCE Library.

In his Civil Engineering Source series More Water Under the Bridge, Brenner shares some thoughts each month about life as a civil engineer, considering bridge engineering from a unique, often comical point of view.

The podcast and radio program This American Life features quirky slice-of-life stories focusing on a theme. In a recent episode, the theme concerned unexpected moments in people’s lives which changed everything. In each story, participants remembered incidents where the trajectory of their lives completely changed.

In one story from 1974, three women were driving down a road in northern California and encountered a hitchhiker. In 1974, and probably since then, young women picking up a hitchhiker were fraught with possibilities, many of them negative. But the women stopped to pick up the young man anyway. It was maybe a little risky, but also fortuitous. The young man, Brian, turned out to be a charmer and not a serial killer (although, it is possible for both things to be true, but it wasn’t in this case). Brian soon ingratiated himself with the women. He invited one of the them, named Cecilia, on a date. Shortly after that, they married. Shortly after that, they had a daughter, Lily. She became a staff writer on This American Life, and fast-forwarding to the year, 2024; Lily narrated her family’s story for the above episode.

It turned out that, apparently, there were some discrepancies about some of the story’s details. The family’s official version was that the hitchhiker, Brian, was in fact hitchhiking. But Cecilia did not remember it that way. Her version was revealed decades later when her daughter Lily interviewed her for the program. According to Cecilia, the three women were not driving and weren’t even in a car. They were walking down a road to a bus stop and met Brian there. He never was a hitchhiker.

Lily was flabbergasted. For decades, the family’s origin story was that Brian was a hitchhiker they picked up while driving. That tale was foundational and the basis of everything that happened since, and suddenly for Lily, the rug was pulled. She needed to learn the truth. Unfortunately, Brian had passed, and the only word available was her mother’s. But then, Lily found an old recording of her father she had never heard. In the recording, he described what really happened.

It turned out both stories were true – sort of. The women remembered they were driving and encountered a charismatic hitchhiker. Cecilia remembered they were walking to a bus stop and met her future husband Brian at the stop.

And through it all, there was a bridge. The family’s origin story was heartfelt to begin with, but it was revealed that a bridge was overseeing it all. Now that there was a bridge, I became really interested.

The bridge was near a bus stop, which was the key location mentioned in both story versions. The various threads of the story versions converged, and a friendly bridge quietly crossed things in the background. It served as a visual chaperone that helped to facilitate the family’s connections and change their lives.

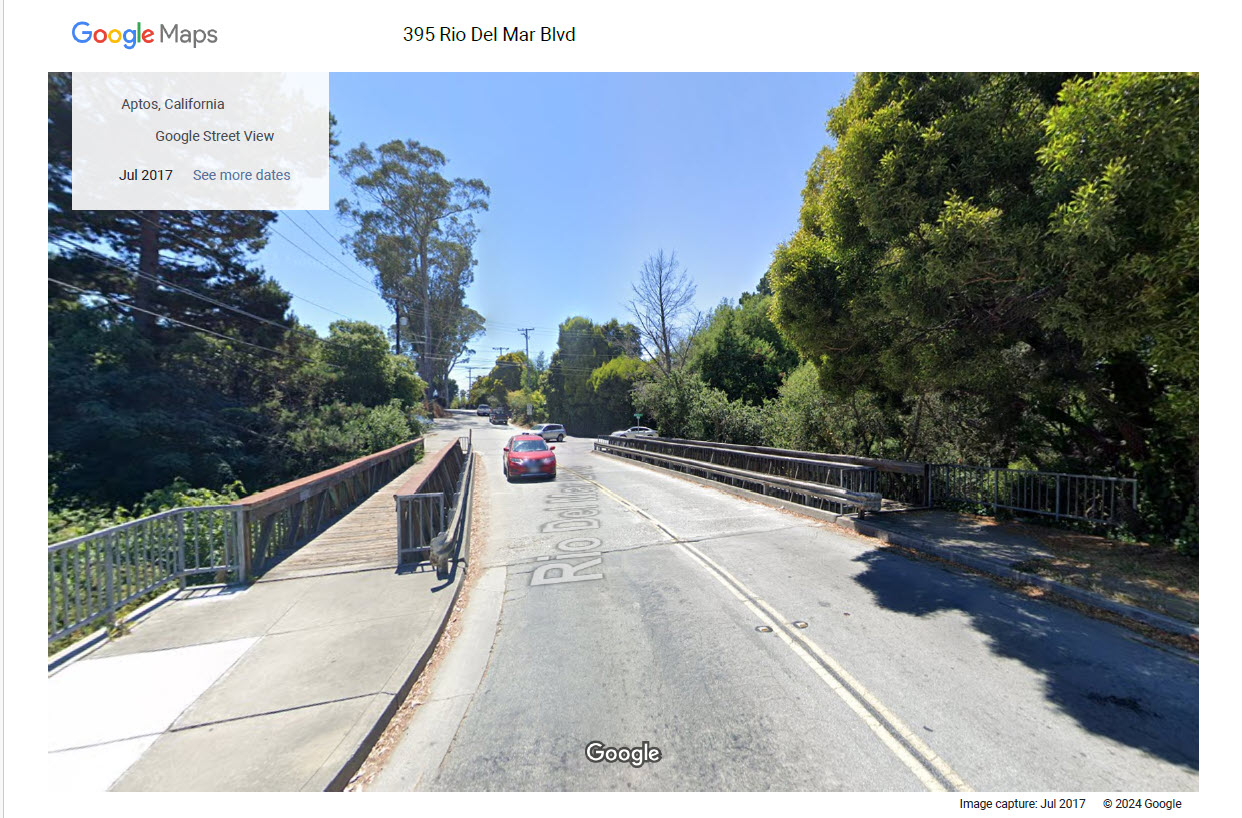

From snippets of information provided in the podcast, I found the bus stop and the bridge:

It looked like a nondescript bridge watching over a nondescript bus stop. But there was a bridge. It begged the question, at least for me: Are life-changing events always overseen by bridges?

On July 4, 1983, I suited up for a run around the Boston Esplanade. It was a perfect, hot summer day, low 90s and partly cloudy with hazy white clouds. My route required a decision about how many bridges crossing the Charles River to string together. This was referred to as a “bridge circuit." Running routes along the river could be from 3 to 12 miles or more. For this run, I decided to connect the Harvard and Longfellow Bridges for a run of about 4 miles.

Outside my graduate school apartment, I started on Memorial Drive. Most of Boston was outdoors that day since the weather didn’t often get very summery, and the river had some cool breezes. The jogging river routes were packed with runners and cyclists. I began at a moderate pace in the warm, post-semester sun, with a gentle wind tailing me and that dirty Charles River water lapping the seawall.

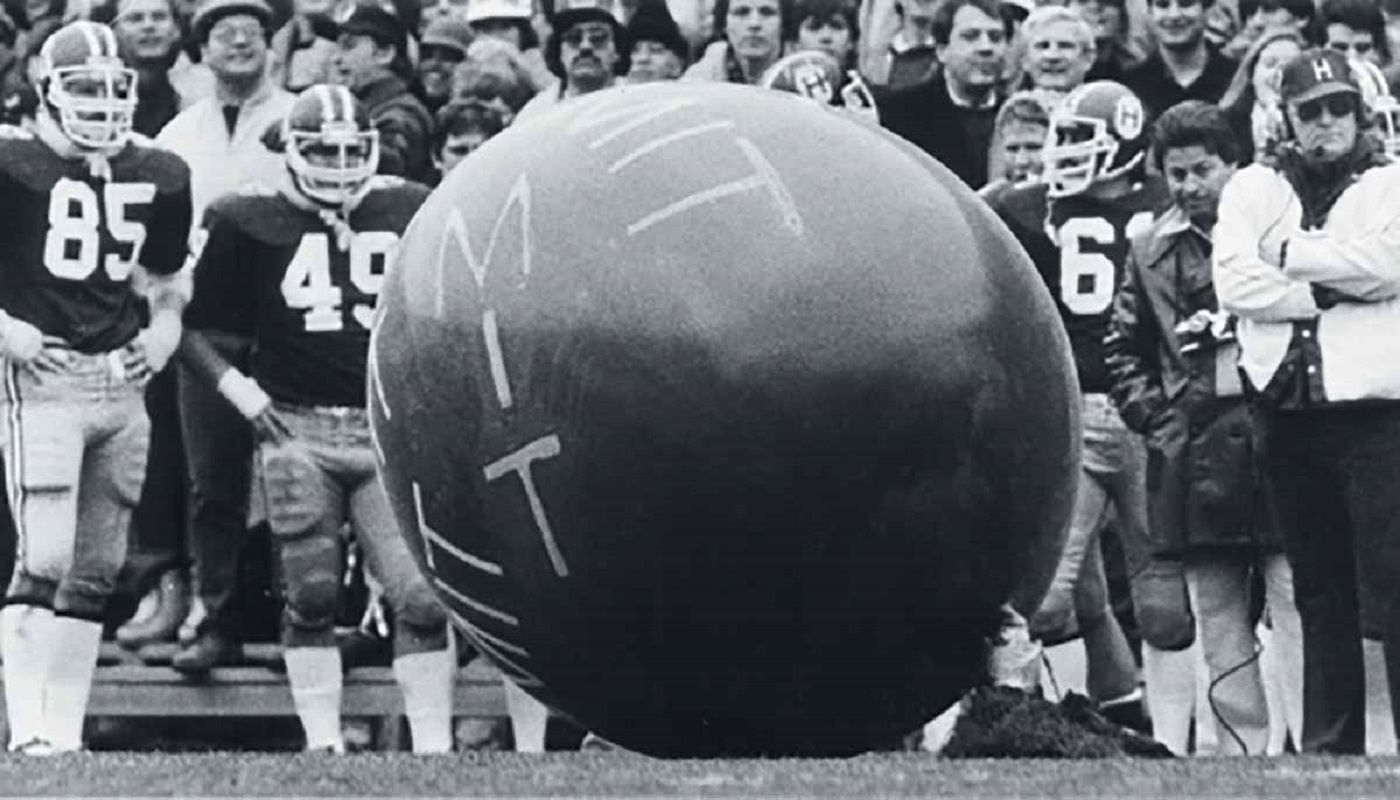

After a half-mile or so, I turned onto the Harvard Bridge. This was the long bridge carrying Massachusetts Avenue over the wide Charles River basin. It is named the “Harvard Bridge” for no good reason since it lands on the Cambridge side of the river in the middle of the MIT campus. The misappropriated name has helped to fuel the generations of rivalry between the two schools. For example, the time when MIT students hid a large weather balloon in the field of the Harvard-Yale football game and remotely inflated it during the second quarter.

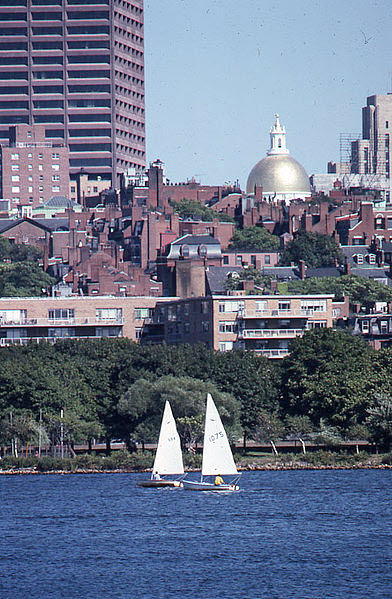

Running on the bridge sidewalk, I looked over the shimmering river to one of the world’s great urban views. The gold dome of the State House glowed on the far bank, surrounded by 19th-century Beacon Hill townhouses. On the river, sailboats glided in the summer breeze.

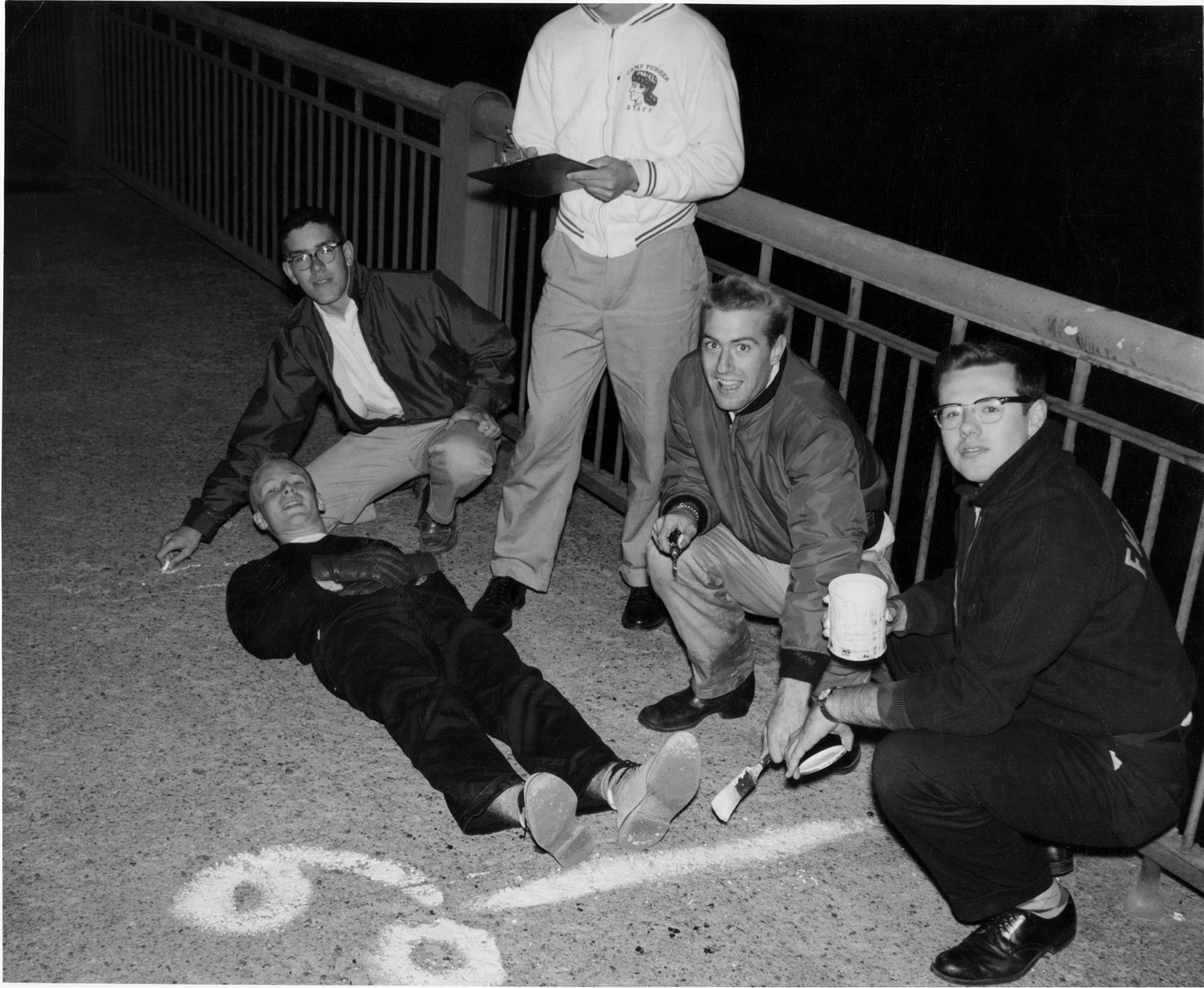

It was a long bridge, but fortunately, helpful markers were painted on the sidewalk. Every few feet or so, lines denoted forward progress in units of “Smoots.” A “Smoot” was a form of measurement based on the length of MIT student Oliver Smoot. In 1957, Mr. Smoot’s fraternity buddies decided to roll him across the bridge to measure its length. Since then, the sidewalk has been repainted every year. When the bridge was repaired in 1986, careful records were maintained to record the Smoots and recreate the measurement markers correctly.

I made it to the Boston side and turned onto the river embankment. It was still early, but partygoers were already camping out getting ready for the upcoming festivities. A major July 4th Boston tradition featured the Boston Pops presenting a concert in the Hatch Shell capped by a rendition of the 1812 Overture and a spectacular fireworks display. There had to have been thousands of people lining the river on their picnic blankets. As I ran by, I didn’t recognize any friends, though it also was unlikely for me to recognize anyone in such a large crowd.

My next destination, the Longfellow Bridge, was around the river curve beyond the concert site. That span presented a much different visual profile than the Harvard Bridge. It was a series of steel deck arches with some monumental details, such as masonry towers known locally as “the salt and pepper shakers.” While the low-slung Harvard Bridge sleekly crossed the river basin, the Longfellow Bridge with its height and mass looked more like a wall, boxing off the river. In a few minutes, I would be past the crowds and up on the bridge deck, returning to the Cambridge bank.

Nathan Holth

Nathan Holth As luck would have it, my trip was delayed. In the thick of the crowds, closer to the concert shell, I spotted a fellow student a bit further back. I debated at first whether to stop. There was research work to do. Lots and lots of research. I could visit with him later, maybe in a few months, once the thesis was written and defended. But the summer haze seemed to clear a bit at that moment. The sun broke through, and streams of light illuminated the dowdy old bridge. Bridges are not sentient, but if they were, the Longfellow Bridge seemed to be advising me to stop and take a little break.

I jogged over to my friend. He had set up a nice picnic spread with a blanket, goodies, and a group of other friends I hadn’t met. The streaming sunlight lit up the site, and everyone glowed. He introduced me to his friend, Lauren.