Tony Gollopeni grew up in Prizren, Kosovo, a "city of bridges" that stand among the community.

Bridges in Prizren serve as points of connection and meeting places for people across the town, split by a river. And, through cycles of conflict, bridges have become a symbol of the city’s remarkable resilience.

One of Prizren’s most iconic bridges, the Stone Bridge, was built in the 16th century. Its longstanding presence is rooted in the strength of the community.

"As a kid, we learned that it was destroyed many times but always rebuilt in the same place in the same shape. That really made me understand the importance of that bridge and all the bridges around it," Gollopeni said.

Gollopeni’s childhood was shaped by heavy Balkan conflict following the collapse of Yugoslavia. Forced to leave Kosovo, he and his family spent several months as refugees in Albania until the fighting ceased.

"When we returned, we found a very different country from what we had left. It was a country that had just undergone war and many parts of it were damaged or destroyed," he said. "But people came back, and the community came together, built the bridges in the places where they were, and even added more bridges."

Gollopeni’s appreciation for bridges and what they represent led him to pursue a career in civil engineering. He moved to the United States for graduate school, and since then, he has worked on over 100 bridges across the country, including almost every bridge in Washington, D.C.

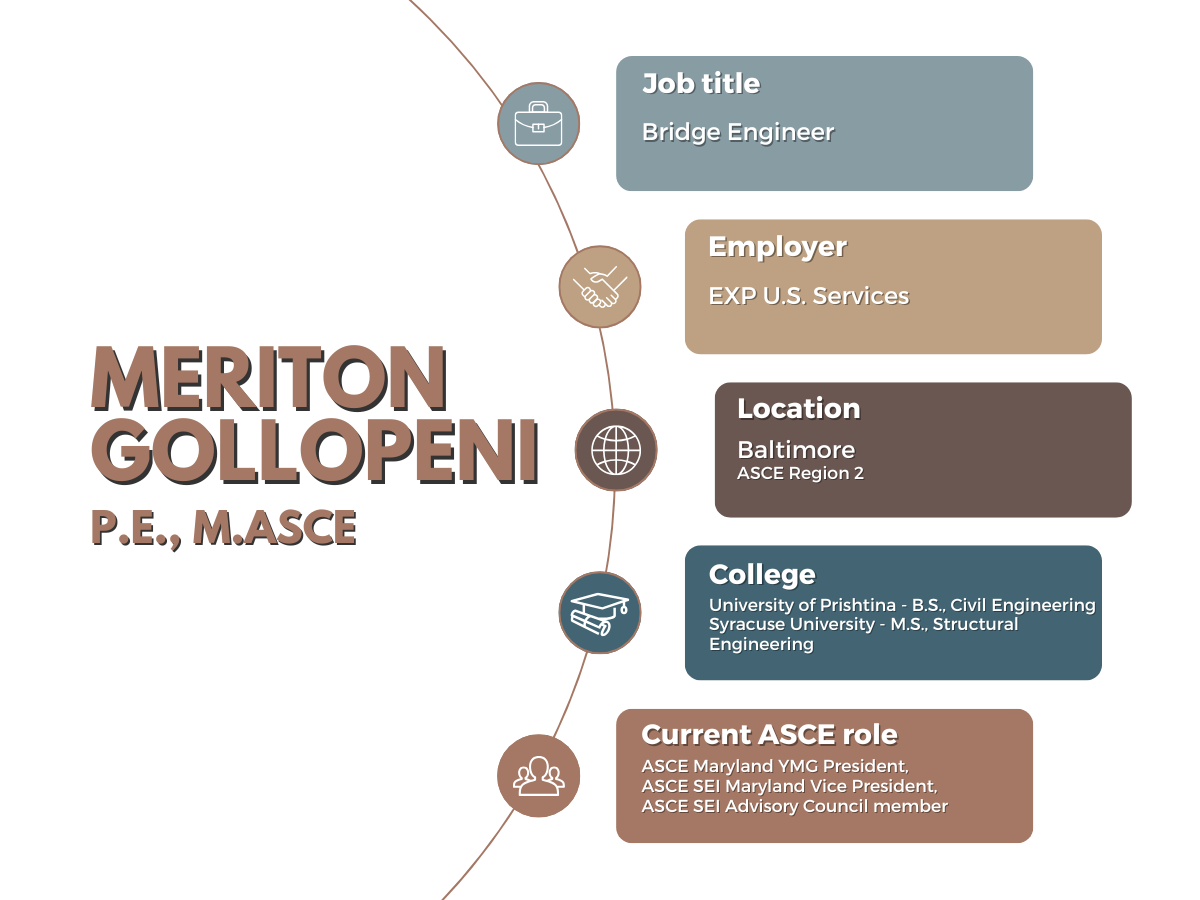

ASCE has honored Gollopeni as a 2025 New Face of Civil Engineering.

He recently discussed his story with Civil Engineering Source.

Civil Engineering Source: What’s the accomplishment or aspect of your career so far that you’re most proud of?

Tony Gollopeni: All of them have had their own merits, but I’ve come to the realization that [what] I'm most proud of is my journey, where I started, and where I am today.

When I was five years old, my family had to flee Kosovo due to the ongoing war in the region. I was a refugee for a few months. Luckily, Kosovo was liberated, and we were able to return to the country. What we were left with was very different, and we had to start making a life with what was still there. That wasn't easy.

Being raised in a postwar country was tough because there weren't a lot of opportunities for education. There weren't a lot of resources for us, but kudos to my parents. They were always very, very strict when it came to education, and they really, really pushed my brother and me to get an education regardless of the conditions we had.

Their pushing really paid off, because I was able to get a good education and a scholarship for an undergraduate degree in Kosovo.

Growing up there, we saw success as going to Europe or America to study or work because there were a lot more opportunities. There were a lot more resources, great education opportunities, and a better life.

That was hard because I was coming from a country that was very different, with less financial resources and universities than America. But I was able to get financial aid, attend Syracuse University, and get a master's degree.

Going from a developing country, starting a new life in America, and going to school there was amazing. Seeing all the resources that people have, the campus, and all the classrooms was very different from Kosovo. That was exciting and a big motivation to study and do great.

I was able to finish my degree in three semesters while I was working about 20 hours a week, the maximum number of hours an international student was allowed to work in the U.S.

During the summer, I was lucky enough to get a very good internship and a couple more scholarships that helped me pay for that degree. Once I graduated, I started working as a bridge engineer in Baltimore and had the chance to work with some great teams. At EXP I have been working on some really interesting bridges all across the U.S.

When I look back at the odds, I feel like I had no business being where I am today. But things worked out for me, and my family and everybody around me worked hard and supported me. I am very proud of my journey!

Source: What kind of impact do you hope to make on the profession?

Gollopeni: Coming from my journey and the way I was brought up into the profession, I really want to help students in a financial way.

I volunteer a lot with ASCE Maryland, SEI Maryland, and some of SEI National. I'm part of the ASCE Maryland Scholarship Committee. Every year, we do fundraising events for scholarships for students in Maryland.

Like me, there are a lot of students who are working hard to become engineers, but sometimes they just don't have the financial means to focus as much as they would like. I want to use my energy to raise awareness and funds for scholarships to help students get affordable education.

Becoming a civil engineer – especially a structural engineer – is hard enough. There's a lot of math and a lot of commitment. The classes get harder and harder every year, and when you add worries about the cost, it gets a lot more difficult. Infrastructure in the U.S. needs a lot of engineers, and at a phase where we don't have enough, we should be bringing in more people.

For some, that might look like outreach and getting some people into civil engineering. But based on my journey, that looks like financially supporting these students so then they can focus on getting an engineering degree.

Source: Your engineering career has heavily focused on bridges. Can you talk about what sparked your interest in the discipline and how that has influenced your career path?

Gollopeni: Bridges were everywhere for me growing up. Just going out, seeing them all the time, and talking about them, I saw how important they were to the community before and after the war.

Whenever we wanted to meet with our friends, a meeting point would always be one of the bridges. I didn't think it was that special at the time, but looking back, anywhere else that I've lived, I’ve never said, "let’s meet at this bridge."

Getting the people across the river was very, very important to the community I was raised in, so I believe, maybe even unconsciously, that this created the connection I have today with bridges in this city.

Something else sparked my interest in bridges at a more comprehensive level when I was a teenager.

Kosovo is a landlocked country. The Adriatic Sea, right on the Mediterranean, seems very close when you look at a map. It's a very, very small distance aerially, but driving through the mountains took about 12 hours because there wasn't much infrastructure there at the time. To get from my hometown to the beach, we had to drive up a mountain, then drive down a mountain, drive up the next mountain, and drive down the next one.

Around 10 years ago, they decided to build a very robust highway that connects the two countries. They built that highway mainly with bridges and tunnels. Now, the drive is only about two to three hours compared to the 12 hours that it was before.

I was a teenager when I first drove on this road. That’s when I really understood the true meaning of infrastructure and the real point of these bridges. More people were connected. They were going on vacations and going to see their family on the other side of the mountains more often.

The economy became much better because we were connected to a port, and goods were being transported in a more efficient way. My final realization was that bridges are very important to not just the infrastructure of a country, but to its communities and prosperity.

When I decided that I wanted to be a civil engineer, I knew I was going to be a bridge engineer.

When I did my master's degree in structural engineering, we had an option to pick bridge engineering classes or building classes. I obviously went for a lot of bridge engineering classes.

I did an internship as a bridge engineer. I was out inspecting bridges, seeing the bridges, touching them, and understanding them at a different level. When I graduated, I started working as a bridge engineer since day one. Since then, I've worked on bridges for five years.