By Jay Landers

A recently completed public playground in Melbourne, Australia, has garnered widespread media attention for its unusual design and emphasis. At first glance, the playground has the feel of a chaotic, hazard-prone site that children should be kept from at all costs: Much of the playground equipment appears to be on or around more than two dozen massive boulders resting on small, wheeled dollies. In places, what look to be leftover construction materials lay strewn about the site, while the surface of the play area appears to be made of stone.

In reality, the playground’s whimsical and downright unconventional elements have been carefully designed and constructed to ensure safety under Standards Australia while enhancing the perception of risk-taking among young parkgoers. Intended to promote a heightened sense of adventure, Melbourne’s new “risk play park” is the brainchild of New Zealand engineer and artist Mike Hewson, who combined art and infrastructure to create an installation that challenges perceptions and offers the reward of greater independence and personal resilience.

Rocks on Wheels

Located within Melbourne’s densely urban neighborhood of Southbank, the AU$2.4 million ($1.6 million) project is the final element of a linear park occupying a section of what used to be one half of a four-lane, split-median roadway that has been converted to two lanes. Situated amid a mix of residential and commercial buildings, the playground is “really crammed” between the roadway, underground high-voltage power lines, and a sewer line, Hewson says.

Titled Rocks on Wheels, the play space was inspired by the 1962 photograph of the same name by American artist Diane Arbus. Although the photo shows fake rocks being conveyed on dollies at Disneyland, Hewson decided to install 24 actual boulders on realistic-looking, domestic-scale furniture dollies in order to make the boulders “look like they're floating,” he says. “The engineering challenge was basically to make” what appeared to be a store-bought dolly that “could support a 16-to-25-ton boulder,” Hewson says.

To achieve this task, Hewson relied heavily on his engineering training and construction experience. After graduating in 2007 with a bachelor’s degree in engineering from the University of Canterbury, in Christchurch, New Zealand, Hewson worked as a project engineer and project manager on a series of heavy construction projects. Hewson later left construction to pursue his artistic ambitions, eventually earning a Master of Fine Arts in visual arts from Columbia University in 2016.

Preparing the boulders

For the boulders, Hewson used basalt bluestone because the locally available stone has long been employed as a building material and as pavers in Melbourne, particularly in its older, historic areas. After the irregularly shaped boulders had been quarried, they were sawn flat on what was to become their undersides when they were positioned in place at the project site.

To ensure the safe transportation and long-term performance of the boulders, Hewson had them post-tensioned. “We made sure the stones were safe to lift,” he says. At the same time, the post-tensioning would help keep the boulders “stable in the public realm for a long time,” he says, “because they're natural forms and they have natural fault lines and we're asking them to sit in quite strange positions.”

Geotechnical concerns also had to be addressed at the project site, which is underlain by a local silt material that is renowned for its high levels of settlement. “The ground conditions were very soft underneath,” Hewson says. As a result, a 500 mm thick concrete waffle slab was constructed to support the dollies on which the boulders rest. “We didn't want individual stones to sink,” he notes. “We wanted the whole site to settle evenly. We can't really afford to have any differential settlement.”

The main playground features, including a circular jungle gym, swings, slides, and numerous steel climbing features, were added to the boulders off-site before the installation of the project. Before transporting the boulders to the site, where they would be positioned by crane, the head contractor — Multipro Civil — drilled lifting points into each one to which chains could be attached. Some of these lifting points then were left in place to be used as handholds by parkgoers.

Precise positioning

The design team used a digital model for the project, in large part to ensure the proper placement of the massive boulders. Not only did the boulders have to be positioned precisely on the small dollies, they had to be located certain distances from one another to comply with fall-zone requirements and other safety standards as required by Australian Standard 4685, Playground equipment and surfacing, Part 1: General safety requirements and test methods. “We were positioning (the boulders) within millimeter accuracy,” Hewson says.

Each boulder had to be brought to the site in its own truck, hoisted by a crane, and carefully placed in position. Meanwhile, the monolithic boulders also “needed to come down exactly flat so they didn't overstress” the dollies, Hewson says.

Given the difficulty of working with a large number of irregularly shaped boulders, the project demanded a “good installation methodology,” Hewson says. Otherwise, the costs associated with traffic management and use of the crane would have threatened to cancel the project, he notes.

Durable illusions

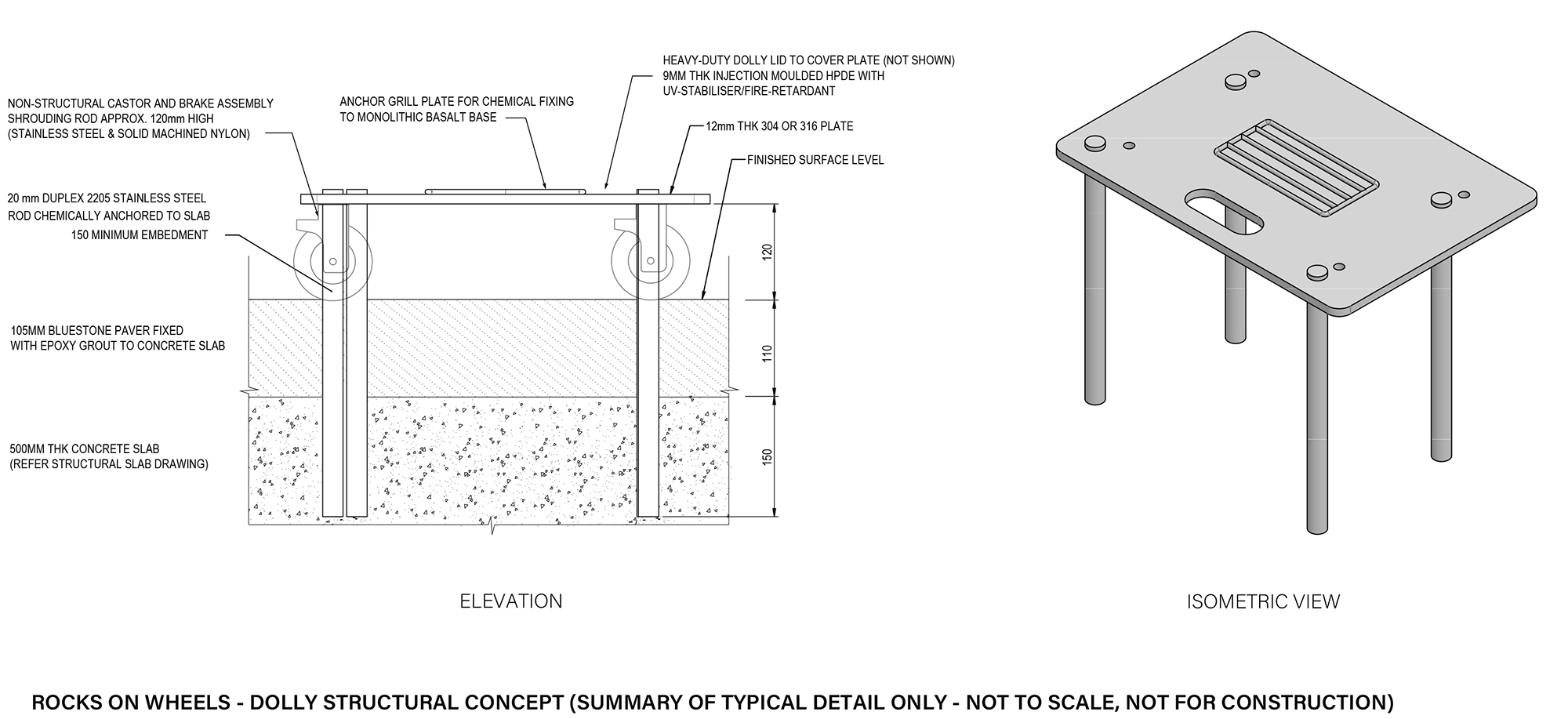

To give the illusion that the boulders are resting on ordinary furniture dollies, Hewson created 76 individual dollies that appear as if they had simply been rolled into place, each with their wheels in the proper position. In reality, each dolly was meticulously designed and built so as to hide the 380 mm long, 20 mm diameter high-strength duplex stainless steel pins that extend through the wheels down into the underlying waffle slab. “These are very stable platforms,” Hewson says.

The dollies, which were chemically anchored to the bottom of the boulders during installation, also had to have a long design life because they “will never be able to be accessed for replacement or refurbishment,” Hewson says. To this end, the dollies consist of a high-density polyethylene cover on top of a stainless steel plate to which the pins are attached.

Off-the-shelf stainless steel casters and solid nylon wheels were machined and cut by means of a water jet to create the hole for the pins. Capable of supporting approximately 6 metric tons, each dolly is “very durable, but deceptively so,” Hewson says.

To comply with child safety regulations, the dollies could not have more than 130 mm of open vertical space beneath them. “This whole park was worked backwards from that dimension,” Hewson says.

“I had to come up with a dolly wheel combination and set that meant that the rock was right on 130 mm off the ground. It couldn't be higher,” Hewson explains. He also had to find a caster set that “had enough room for a large enough wheel that could hide the small flat spot in the bottom of the wheel to deceive the eye perfectly that there was no pin going up through the wheel.”

To give the illusion that the playground’s surface consists of bluestone pavers, Hewson created a rubber ground surface that mimics the natural stone in appearance. The rubber is used as the surface throughout the park, except directly beneath the boulders.

Because the boulders cannot be moved to facilitate maintenance beneath them, the boulders and their accompanying dollies are underlain by actual bluestone pavers. This practicality reflects Hewson’s goal to create an installation that will last well into the future. “I try to design things for a very long and very ambitious design life,” he says.

A ‘sense of adventure’

The Melbourne installation is Hewson’s fifth major permanent commission since 2018, all in Australia. For the project, the artist teamed with the city of Melbourne’s design team, which provided planning, landscape architecture, and industrial design services. Event Engineering served as structural designer, while Tonkin + Taylor provided specialist geology services. Felicetti Consulting Engineers designed the project’s foundations, while quarry supplier Bamstone provided the bluestone that was used in the project.

Although designed with permanence in mind, Hewson’s installations all have “an element of precarity that sits in them, and it requires a lot of innovation and planning and understanding of materials to pull these things off,” he says.

For example, on some of the boulders in the Melbourne installation, Hewson affixed such materials as steel bars, pipes, rocks, and even hardened core samples left over from the project. Intended to “look like waste offcuts the builder forgot to remove,” the materials have been carefully placed and anchored to prevent entrapment of clothing as well as hands, fingers, and other body parts, he says. “All of these things are actually helping (the playground) pass the code.”

The haphazard appearance of much of the playground is intentional, Hewson says. “The goal is to try and create a sense of adventure for children.”

As with some of his previous installations, the initial public reaction to Rocks on Wheels was, well, a bit rocky. Upon its opening in November, the park generated more than a few expressions of concern in the press and on Twitter.

The most common concerns had to do with children’s safety, a fear that is completely unfounded in Hewson’s opinion. “A lot of the armchair critics throw their hands up in the air when they see my parks because from photographs they don't look like they've been well considered,” he says. “But I think through all of these things.”

The playground also had to pass a safety inspection before it could open, says Sally Capp, the lord mayor of Melbourne. “Rigorous testing has been undertaken in consultation with child safety experts to ensure the playground is safe for everyone,” Capp says. “This is a different approach to a playground, and we should embrace different. So far, the community response has been overwhelmingly positive.”

That response stems from the fact that the playground “embodies certain values that we (as a population) are realizing we need,” Hewson says. “When you're thinking about the future of society, we need to be adaptable in order to be resilient. (And) in order to be adaptable, we need to be able to respond to unfamiliar and irregular environments — surprising environments.”

This article first appeared in Civil Engineering Online.