By Catherine A. Cardno, Ph.D.

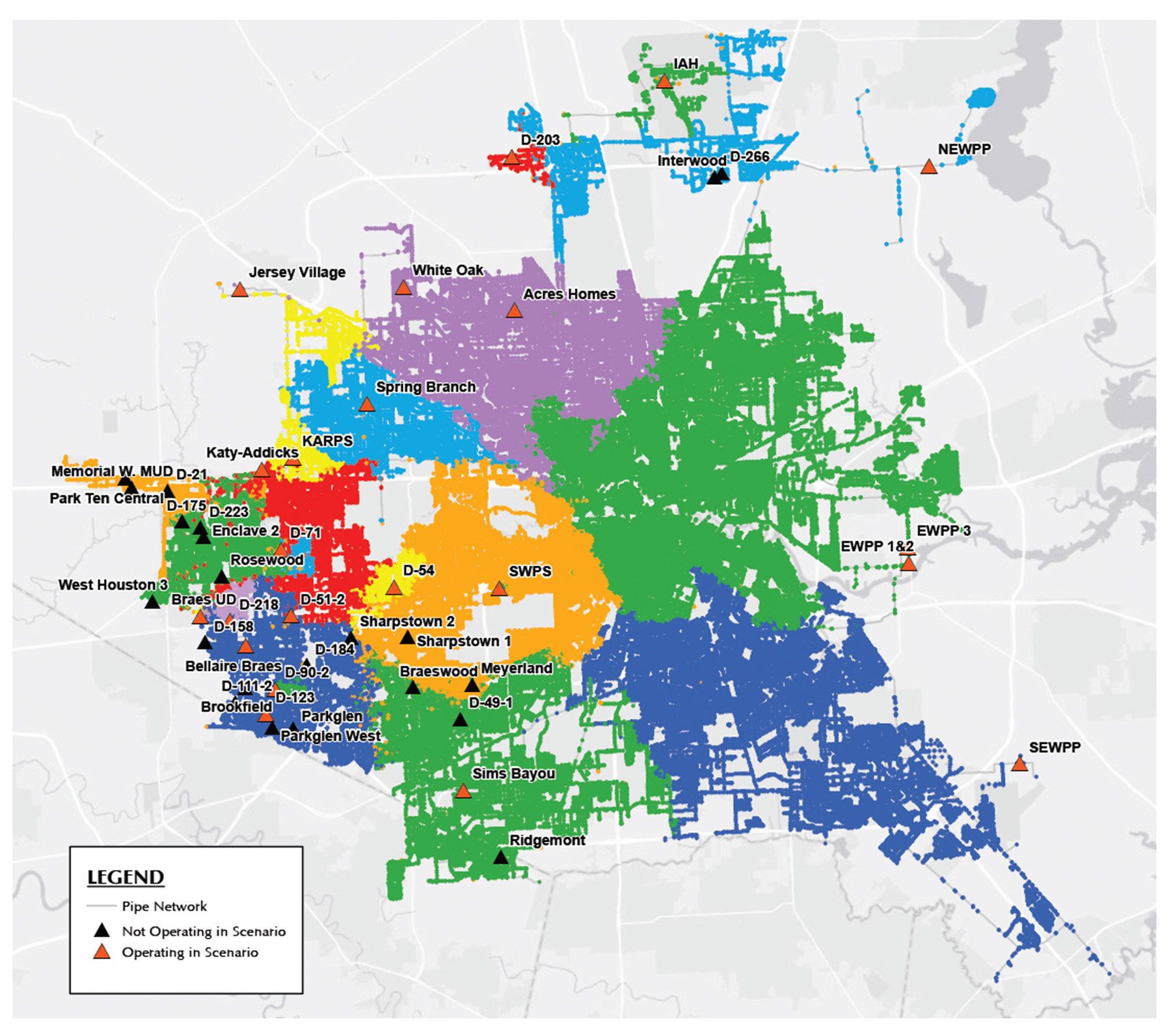

A comprehensive digital twin computer model is being developed for Houston Public Works, the agency responsible for delivering drinking water to more than 5 million people in the city’s metropolitan area. The agency oversees a complex system that encompasses 671 sq mi, providing more than 600 mgd of drinking water via three surface water treatment plants, seven repump stations, 39 groundwater plants, and about 7,500 mi of piping.

The digital twin will accurately represent the city’s entire water distribution and transmission system, including all piping, valves, facilities, storage tanks, and wells, according to Melissa Mack, P.E., PMP, M.ASCE, a vice president and principal at Lockwood, Andrews & Newnam’s Houston office. Mack is LAN’s project manager for the endeavor.

The process to develop the digital twin began in 2016, with the preliminary phases completed by 2019, according to Mack. To create the initial model, information on the existing waterlines, valve locations, elevations, and water usage patterns was gathered from multiple sources, including geographic information system data, lidar, and supervisory control and data acquisition feeds.

In addition to data feeds, the additional pipe detail built into the hydraulic model will allow for higher-resolution visualization of the entire system. Prior to this, the system included only larger waterlines that limited the level of detail available in model results. The new hydraulic model, which is being used to create the digital twin “includes all pipes within the city’s transmission/distribution system, while the previous model was what we call a ‘skeletonized model’ that included only pipes 12 in. and larger, which usually excludes neighborhoods,” explains Amy Byland, P.E., a water conveyance engineer in LAN’s Houston office. Byland was the lead hydraulic modeler for the company on the digital twin project.

The model is now in the refinement stage. “Significant effort has been put into developing a quality, all-pipes hydraulic model over the past five years,” Byland says. “However, the hydraulic model is only part of a digital twin. Houston (Public Works) is currently working toward developing real-time operation, condition, and consumption data to be coupled with the hydraulic model in their push to become a true digital twin utility.”

“So far, we have learned that (a) digital twin solution needs continuous improvement,” says Satish Tripathi, P.E., M.ASCE, managing engineer for water and infrastructure planning for the city of Houston. The continuous improvement will enable the model to provide increasing utility to its users — engineers, planners, operators, and others — and offer insight into possible operational changes that can bring benefits such as improved levels of service and increased energy efficiency.

Currently, the city is integrating advanced metering infrastructure into the system so that real-time data can be used within the model, Mack says. “A digital twin is only as good as the data you have,” she notes.

As part of this effort, in the near term the team plans to develop “full integration of (the) hydraulic model, operational data, and real-time sensor data, (including) pressure, water consumption, and water quality,” Tripathi says. This will be done by “developing simple in-house tools to consume/use integrated data in (the) decision-making process,” he says. Integrating these additional data sources into the digital twin will allow for better model calibration and improved accuracy.

In the long term, Houston Public Works hopes to develop a real-time decision-making system that will operate using artificial intelligence and machine learning, Tripathi says. “The ultimate goal is to be able to do predictive modeling,” Mack explains. That would be “a huge benefit to the engineering community and community at large” because it would enable the team to better resolve problems and more reliably plan for the future.

Operationally, this would mean that any need to take pipes offline for repairs or maintenance could be assessed and the plans refined so that the shutdown’s impact on the system as a whole could be minimized, Mack says.

Once it is fully developed, the digital twin will be able to accurately replicate the physical system’s behavior and performance. It will integrate data from the city’s existing SCADA feeds, explains Mack. It will also be able to simulate operational scenarios, helping the city define the needs of its capital improvement projects and support its water quality management, Mack says.

Water usage within the region is rising, and within the next 20 years it is anticipated that the agency will need to increase its capacity to more than 1,000 mgd. The digital twin will help the agency determine where in the system it will be necessary to add that capacity to meet future demand, Mack says. The model will also help the agency reduce its groundwater use in favor of surface water for the majority of its drinking water. This transition has been a long time coming in the region and is part of a plan to limit the ground subsidence that the area is experiencing from removing too much water from underground aquifers, Mack says.

Funding is currently the biggest issue the team faces in its efforts to manage data collection and complete the digital twin, according to Tripathi. “We are doing pilot projects in small areas,” he says. “Once we see the results in such areas, and if (the) results are financially/economically attractive, we can justify the investment for (the) whole city.”

Creating a digital twin is “a journey, not just a tool,” Tripathi concludes. “It is an ongoing process.”

Catherine A. Cardno, Ph.D., is the managing editor of Civil Engineering Online.

This article first appeared in the March/April 2022 issue of Civil Engineering as “Digital Twin in Development for Houston Water System.”