By Leslie Nemo

The Bronx River Parkway provided recreational space and a model for future traffic development.

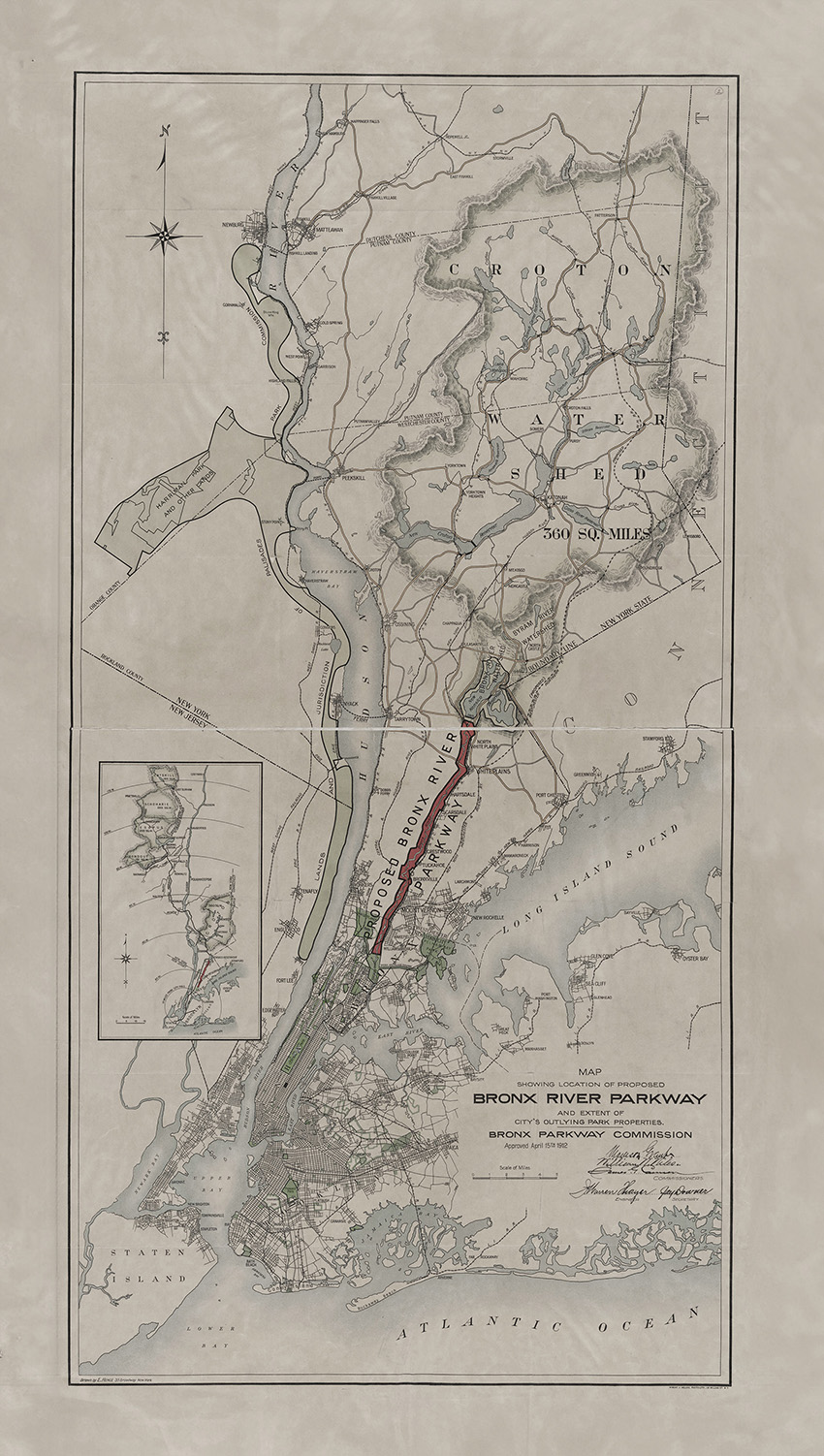

In the early 1900s, concern about how industrialization was damaging natural resources spread through the nation, even reaching New York City, the largest city at the time, and its expanding suburbs. The original Bronx River Parkway — a 16 mi stretch of scenic roadway running from the New York Botanical Gardens in the Bronx (southern terminus) to the Kensico Dam Plaza in Valhalla, New York (northern terminus) — was a product of the era’s appetite for beautiful, nature-like leisure spaces.

The socialites, legislators, and other wealthy New Yorkers who pushed for the engineered landscape claimed that the Bronx River needed rescuing from the factory pollution and development along its banks. Records show that not all these claims were true.

But however honest these claims were, the campaign succeeded in creating a new park and, incidentally, set standards that future highway and bridge designers would follow.

Part of the idea for cleaning and preserving some of the Bronx River stemmed from concern about another public nature area. The city bought 640 acres to create Bronx Park in late 1888, and a decade later, over a third of the acquired space became the Bronx Zoo.

As visitors trekked to this latest city attraction, the New York Zoological Society worried about the contamination in the river coursing through the center of its land.

The Bronx River had been the site of industrial development since the mid-1880s. The New York Central Railroad built tracks in the region about 40 years earlier, and stables, factories, homes, and dumps followed. Construction of a regional sewer system began in 1905, but once completed, many refused to connect to it.

Much of the resulting river pollution concentrated in the Bronx Park’s lakes. The stench, the Zoological Society thought, was harmful to visitors and animals.

The same year the sewer went into place, the Zoological Society partnered with New York City and Westchester County governments to propose that the state create a Bronx Parkway Commission to study possible solutions to the pollution problem.

A year of analyses and surveys later, the BPC issued a report suggesting that roughly 15 mi of land alongside the river be turned into a reserve. Not only would municipal control of the banks and floodplains keep the water from being polluted, but the long, slim park could carry a roadway for cars headed to the countryside. The BPC envisioned casual motorists using the drive for a leisure activity because, at the time, “the car was still regarded as an expensive toy for wealthy hobbyists,” wrote National Park Service historian Timothy Davis, Ph.D., in the Engineering History and Heritage article, “Documenting New York’s Bronx River Parkway, USA.” Many automobiles on the streets were still electric, and it would be a few years before the Ford Model T hit the market and made driving a more common activity.

In 1907, the New York state legislature turned the BPC proposal into law, establishing the commission — a trio made up of representatives from Westchester County, the Bronx, and Manhattan — to carry out the parkway development. Two of the seats went to Madison Grant (Manhattan) and William Niles (Bronx), men with strong ties to the founding and operation of the Bronx Zoo who had petitioned for the preserve.

Soon after the law went into effect, the project came to a standstill. The 1907 law stipulated that funds could only be spent once the New York City Board of Estimate and Apportionment gave approval. The BPC had stated that New Yorkers, as opposed to Westchester County residents, would use the park the most and should foot a larger proportion of the bill. With the city responsible for three-quarters of the total cost, the board worried that expenses would balloon over time, according to the Historic American Engineering Record report “Bronx River Parkway Reservation (HAER No. NY-327).” That fear would eventually be validated.

While waiting for board approval and stymied without board funding, the members of the BPC spent roughly five years — as well as their own money — to make the parkway palatable to New York businesses and communities. Visits to property owners along the Bronx River coaxed some landowners into donating land or moving their polluting structures farther away from the water.

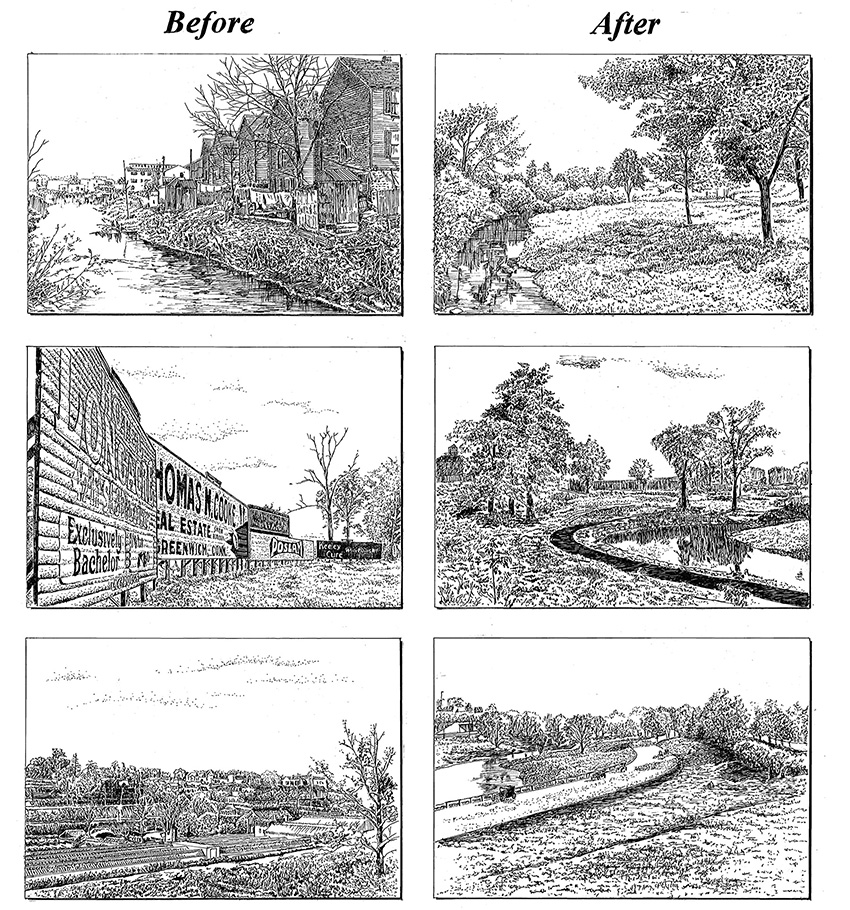

During this time, the BPC also kicked off a media campaign persuading private citizens to support the project. In 1911 and 1912, newspapers across Westchester and New York City ran nearly identical stories describing the threatening consequences of a polluted river and suggesting how locals might benefit, economically and otherwise, from the miles of park. Reports were filled with photos that contrasted dirty development near the water to sections that still looked pristine, aiming to show the public what the parkway could achieve.

However, all was not as it seemed. Dozens of photographs taken by the BPC of already-owned or soon-to-be-acquired land showed respectable-looking hotels, small businesses, and even newer, middle-class homes, according to Davis in the 2007 article, “The Bronx River Parkway and photography as an instrument of landscape reform,” which appeared in Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes: An International Quarterly. Images of those structures conveniently did not make it into the public reports. “In addition to presenting a highly selective impression of the types of buildings to be removed, the published photographs were carefully calculated to portray the existing landscape in the worst possible light as unsightly, undesirable, and ripe for removal in the interests of landscape reform,” according to Davis.

Housing photos that “proved” the value of the project often showed tenements that contrasted with the suburban gentrification goals of Westchester County.

Eventually, the New York City Board of Estimate and Apportionment gave in to the campaign, passing legislation that allowed the BPC to officially start acquiring land. Purchased property made up two-thirds of the total parkway, at a cost of about $4.6 million, while donations and condemnations made up the rest.

As soon as segments of property belonged to the BPC, staff began rehabilitation work. For example, the BPC dropped dye into the plumbing systems of homes to see which ones were hooked up to the sewer system or were dumping into the river. Violators were advised on how to connect to the waste infrastructure, or if that did not work, they were threatened with lawsuits.

Later, many homes would be removed and rebuilt elsewhere.

Also in 1913, the BPC hired Hermann Merkel, a landscape architect and forester at the Bronx Zoo and nearby botanical gardens, to begin property modifications. Along with forester Albert N. Robson, Merkel had staff prune, plant, and remove thousands of trees.

In addition, the pair convinced the BPC to start its own nursery, which eventually had 75,000 vines, shrubs, and other plants. The BPC also forced business owners to remove billboards along 7 mi of land and strategically planted trees in their place.

Clearing and “cleaning” the land to make it suitable for vegetation was a major task, and it often included repair work. In an area near Scarsdale, work crews were tasked with repairing damage done by contractors who had built the Bronx Valley sewer.

The crews had backfilled the sewer excavations with “broken rock and boulders to a depth of twenty feet,” according to the HAER report, “but deposited no fine material between the stones. The result was a ‘rocky waste’ that did not support vegetation.”

The report continues: “The BPC discovered that even if a layer of soil was laid over the rocks, it would quickly wash away leaving raw stones that could not retain enough moisture to promote plant growth.” To fix this problem, the BPC used a pump mounted on a scow that flushed soil onto the rock fill. “The water carried the soil to the full depth of the original excavation and after nearly two months of pumping almost continually, the area was seeded and planted,” per the HAER report.

The river itself also needed rerouting to fit the BPC’s naturalistic ambitions. When the rail system was built, workers had channeled the river into a ditch in an attempt to make the tracks as straight as possible, so Merkel had portions regraded and widened to simulate the contours of a natural stream. Chief engineer Jay Downer, M.ASCE, took advantage of these alterations to construct a flood protection system for the roadway. The water and land were at a similar grade — the latter was too soggy to support a roadway foundation — and the least expensive solution was to dredge the river 3 ft below the low water level.

In 1917, Downer bought a custom-built dredger from the Bucyrus Co. of Milwaukee, which was also building bespoke equipment for the New York subway, as well as a Monighan dragline excavator to help with this work.

More innovation lay down the line for the project due to World War I and its aftermath. By October 1918, near the end of the war, the BPC had lost more than 80% of its workforce to the military. While the war raged, the project largely maintained landscapes or finished a handful of bridge projects. When work resumed in full force in 1919, the nation was in the midst of skyrocketing inflation, and the BPC needed to cut costs.

Acquiring surplus construction equipment from the U.S. War Department was one method of managing the budget. Downer used the federal giveaway program to obtain an Austin caterpillar crane, a road roller, five steam shovels, several kinds of pipe, and other items, ultimately assembling $400,000 worth of materials and equipment that only cost the project freight and handling charges, according to the HAER report.

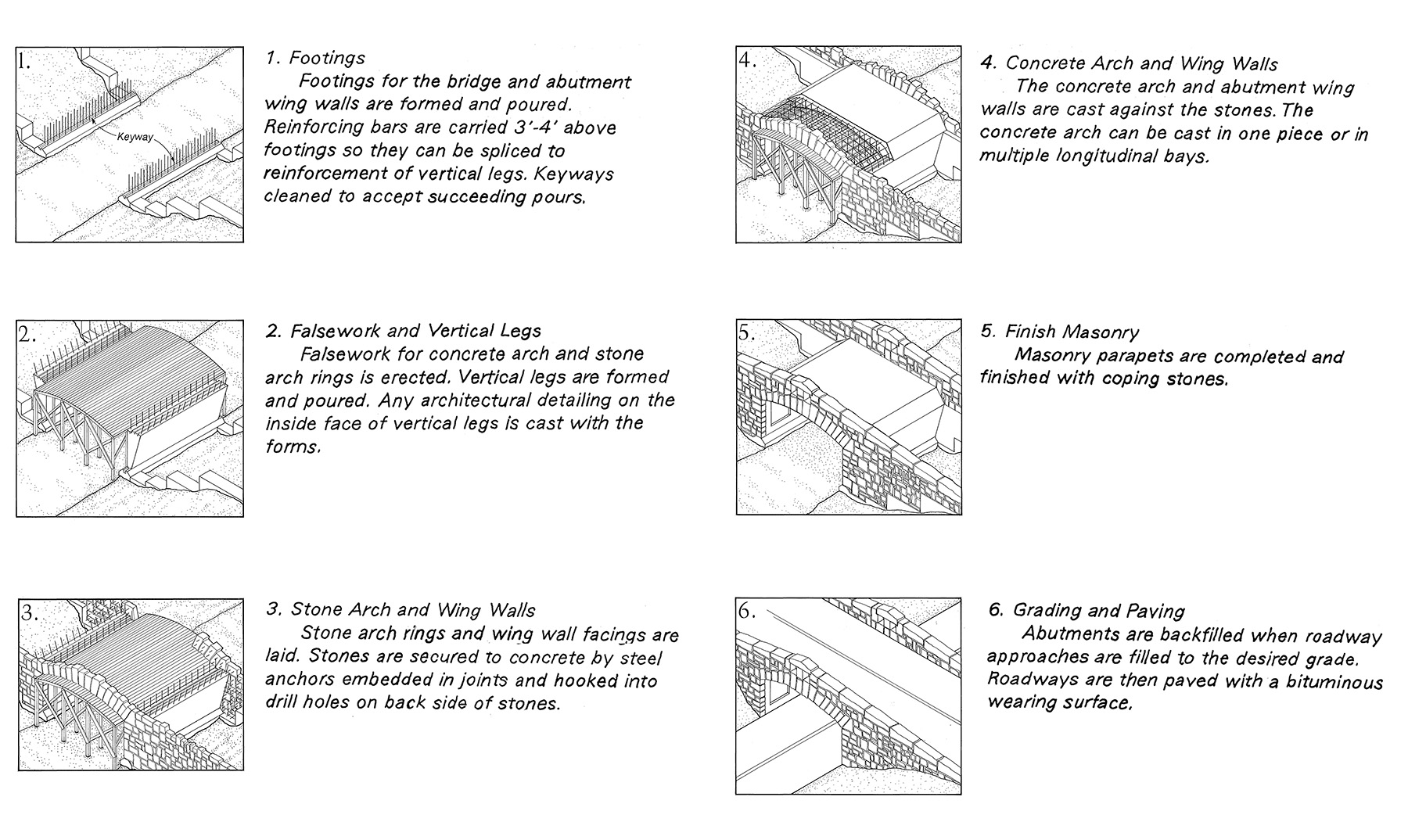

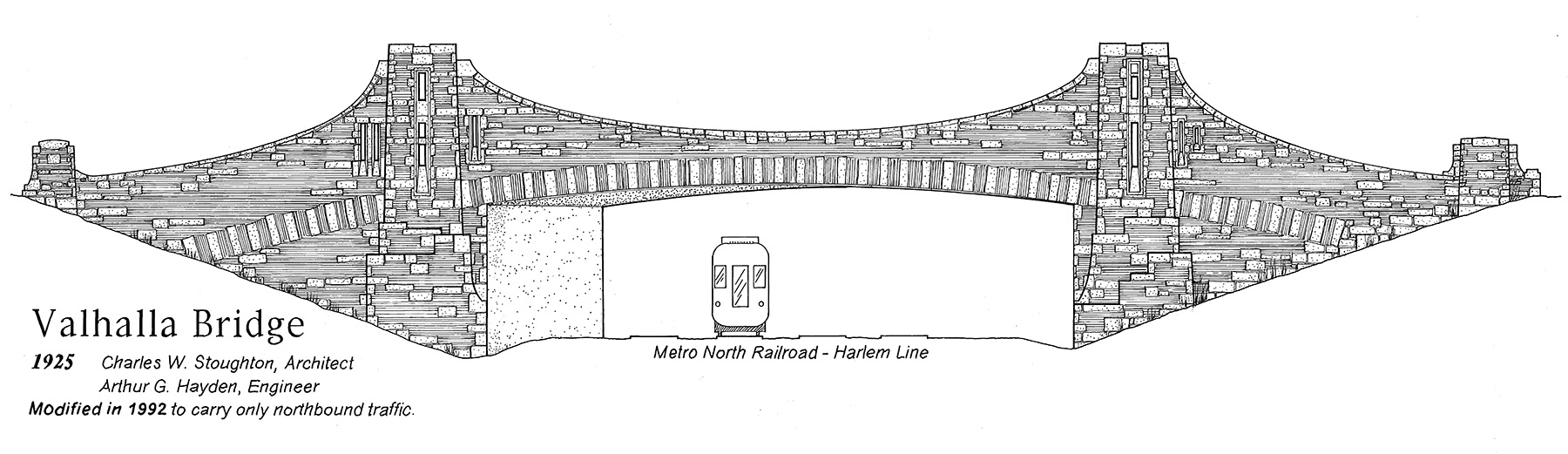

Other expenses, like construction itself, had to be reduced too. Before the war, the BPC built some standard reinforced-concrete arch bridges “embellished with granite arch rings and rubble facing for the spandrels,” per the HAER report. But the overall project had 37 structures to be built — bridges, viaducts, and grade separations. The project needed a design that required less excavation and smaller abutments. So in December 1921, engineer Arthur Hayden, M.ASCE, suggested a design he referred to as a “rigid-frame” bridge, which was cheaper to build and structurally stronger.

HAER attributes the invention of the design to Hayden, as did some of the BPC’s own reports, though historian Carl W. Condit suggested that the engineer simply introduced an existing design to his American colleagues.

Either way, the BPC adopted Hayden’s design after first having a team at Columbia University and bridge engineer John A.L. Waddell, Hon.M.ASCE, confirm the strength of the design. The rigid-frame style required less of everything: less concrete for the abutments and bridge frame members, less fill for the approaches, less excavation for the abutments, and a lower clearance since the flatter shape provided more headroom for roadway lanes it passed over compared to arch bridges, according to the HAER report.

Placed at four grade crossing locations, the rigid-frame bridge saved the BPC between $700 and $1,000 per bridge, according to Hayden’s estimates. The BPC also contracted for a handful of other bridge designs, like reinforced-concrete beam and slab styles, to be built into the parkway.

One rigid-frame bridge, the Valhalla Bridge, was even disguised with brick and stone to look more like a suspension bridge.

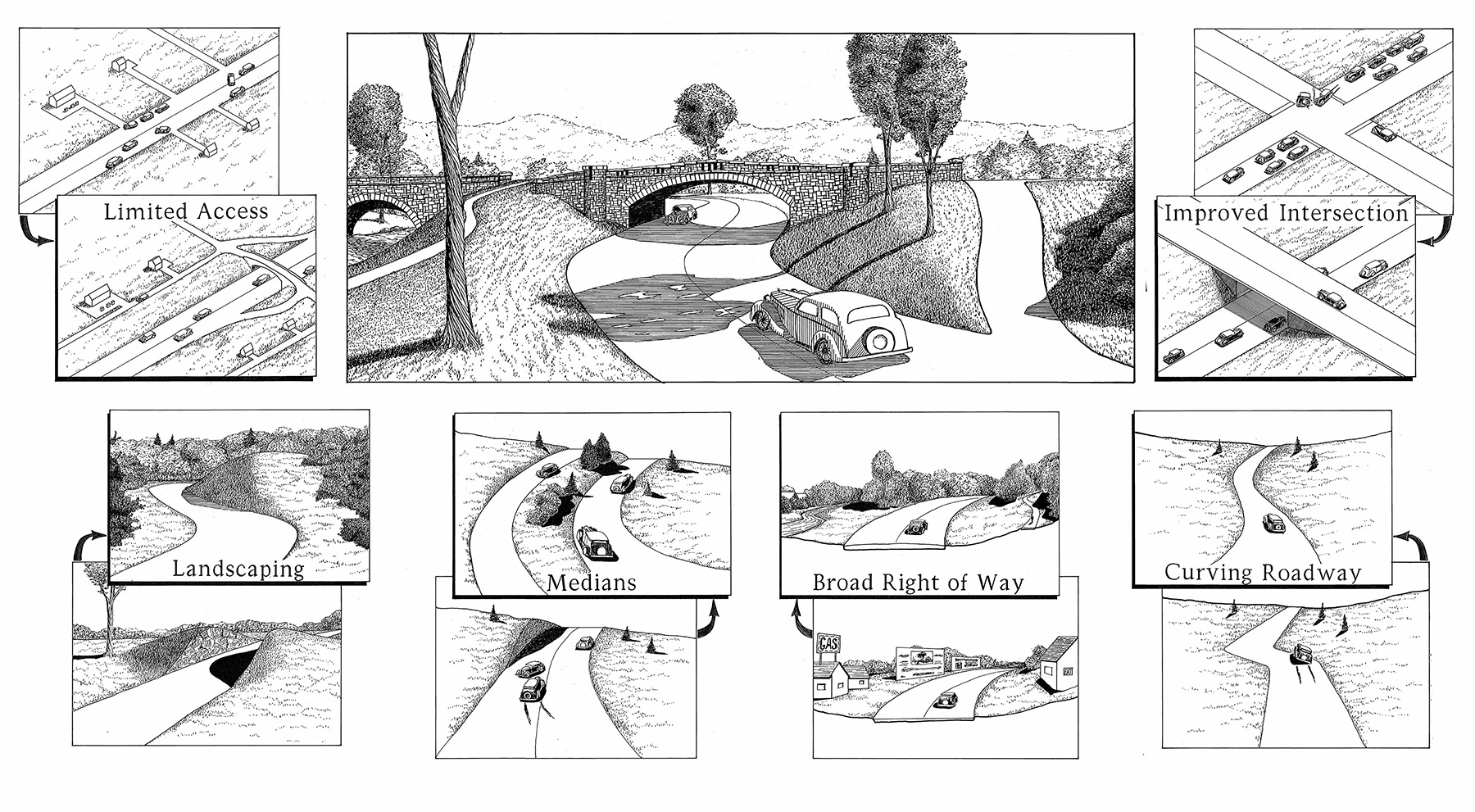

Besides the bridges, a major project design feature was the main roadway itself. Merkel made most of the roadway plans and opted for a 40 ft wide, four-lane street. According to the HAER report, the earliest designs called for features such as landscaped medians to separate lanes carrying traffic in opposite directions, as well as grade-separated crossings.

Size and budget restrictions kept most of Merkel’s plans from being realized, but when the parkway opened, a few short stretches had median-divided lanes, and there were nine grade-separated interchanges.

The parkway is considered to be the first to employ several design principles in a systematic, large-scale manner: “curvilinear roadways that followed the natural contours of the landscape, grade separations, medians, separated roadways on varying grades, a broad right-of-way, limited access, and a naturalistic landscape,” according to HAER.

The BPC opened segments of the road and park as they were completed. Community groups received one-year permits for playgrounds and baseball fields as early as 1914, and sections of the road were available in 1922. The last bridge was completed on Aug. 15, 1925, and on November 5, officials held a dedication ceremony.

Just as the board feared, the project costs had ballooned. By 1922, the two governments funding the work had paid almost $11.8 million, which temporarily caused the city finance board to withhold payments. The total bill came to approximately $16.5 million, according to the final report from the commission.

The BPC had managed impressive feats to realize this project. The commission knit together 1,338 parcels of land, introduced the U.S. to a bridge design that would spread throughout the nation, and even designed and installed its own rustic light posts equipped with underground transmission lines. But there was one glaring problem with the final design: “The parkway is too small and the parkway drive too narrow,” the BPC wrote in its final report. “Your Commissioners are quite aware of that fact and have been aware of it from the outset.”

By 1924, there were more than 15 million cars on U.S. roads, considerably more than there were when the parkway was first proposed. Vehicles were getting faster, too, a problem for streets with curves and embankments meant to facilitate a leisurely 25 to 30 mph drive. “Although intended for pleasure vehicles, the roadway quickly turned into a busy commuter thoroughfare,” according to HAER. By 1931, roughly 30,000 vehicles a day were driving on the parkway.

Slowly, parkway design throughout the U.S. moved away from what the Bronx River Parkway offered. Roads lengthened to connect more distant locations, and longer and wider curves developed to accommodate different driving needs. The Bronx version morphed to stay useful, too. But when its earliest passengers cut through beautiful scenery with the constant accompaniment of the Bronx River itself, they were enjoying cutting-edge design.

Leslie Nemo is a journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, who writes about science, culture, and the environment.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “A Park with a Side of Highway.”