By Kayt Sukel

When asked to conjure a picture of Hawaii’s beaches, you likely think of pristine, clear waters and white sand, not a hundred thousand unexploded bombs littering the ocean floor just a few miles offshore. Yet not far from the coastline of volcanic tide pools and holiday high-rises, you will find a dangerous legacy left over from World War II. Margo Edwards, Ph.D., director of the Applied Research Laboratory at the University of Hawai’i, says that at the end of the war, the U.S. military disposed of tons of munitions in the nearby Pacific Ocean.

“I don’t want to make excuses for the people back in the 1940s, but their options were not our options,” Edwards explains. “They didn’t have the chemical neutralization processes that we do now. Their options were literally to burn, which is a very bad idea; bury, which could potentially go into the water table; or throw these munitions out to sea. ... Out of those three options, I think a lot of us would have gone in the same direction.”

The problem, however, is that 70 years later those munitions present a clear and present danger — and not just in Hawaii, but across the globe. Travel to the North and Baltic seas, the Marshall Islands, Puerto Rico, and even the coast off Los Angeles, and you’ll find miles of underwater munition dumping sites. And now, government agencies are looking for safe and inexpensive ways to clean them up.

The reasons for the cleanups are many. Some weapons may still be armed, which could result in an explosion if a fisherman, for example, catches an errant bomb in a net. But there are also grave environmental concerns since these munitions are breaking down in the water, says Penny Vlahos, Ph.D., professor of marine sciences at the University of Connecticut. The chemical byproducts from the degrading ordnance, which include chemicals like mustard gas, may be affecting marine ecosystems in ways researchers do not fully understand yet.

Most of the chemicals contained within unexploded bombs or other munitions break down pretty quickly, says Vlahos. That can cause environmental issues. “Any organisms that feed in that area, if they get eaten and caught by us or go up the food chain, with compounds like mustard gas and things like that, it’s really toxic. In Europe, the problem is even bigger than it is here because many of the chemical compounds manufactured here were exported to Europe.”

The German Environment Agency estimates that there are some 1.6 million tons of munitions waste in northern European bodies of water. Because these water bodies lack the strong currents of the Pacific, there is now a “stew with nasty chemicals sort of sinking down to the bottom,” says Edwards, which may be further exacerbating munitions breakdown. It’s a complex problem, she adds, that needs multiple approaches to successfully manage.

Different environments, different needs

Many countries have created programs and set aside funding to help clean up underwater munitions. However, each site is unique and may require different tools to detect and assess the various munitions in question. Leif Christensen, Ph.D., a researcher at the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence, is working to develop autonomous underwater robots that not only identify but also recover munitions in the Baltic and North seas, which have limited visibility due to sediment in the water.

“Our project here is more concerned with how we get the ordnance out,” he explains. “We are training AI so that it has the kind of expertise a very experienced diver has. That kind of diver knows, okay, this is a 500-pound bomb. He will see it is partly submerged in the sediment, extending 30 cm into the ground. And then there may be something where he could attach a belt to remove it. We are training AI to do exactly this kind of reasoning.”

In Hawaii, where visibility is not an issue, Edwards and her colleagues are concentrating on inexpensive solutions to understand the risks in shallower environments where the chances are greater for people to encounter munitions.

The dilemma is figuring out how an uncrewed underwater system can make a map using sidescan sonar or a camera to find buried munitions, says Edwards. “You can go out and ‘mow the lawn’ back and forth (and) systematically start mapping around areas and see where (the munitions are).”

Once a map is created, researchers can then add automatic cataloging software that will detect if a munition is there, enabling researchers to do a more complete survey of the area.

Edwards says the challenge then becomes how to do that safely. It may not be safe to expose divers to the chemical byproducts leaching from the ordnance. And autonomous submersibles may not be advanced enough to “dig down into the sediment to sample it without touching the (munition), without hurting any critters,” she adds.

The assessment problem

As AI and robotics become more adept at identifying munitions along the seafloor, even at great depths, the next issue is assessing what can and should be removed. As Vlahos noted earlier, many chemical compounds in munitions may have leached out years earlier. Edwards says that many old munition shells have thriving coral ecosystems living on them. “If that munition is completely empty, and it’s now got coral on it, when do you do more harm than good by removing it?”

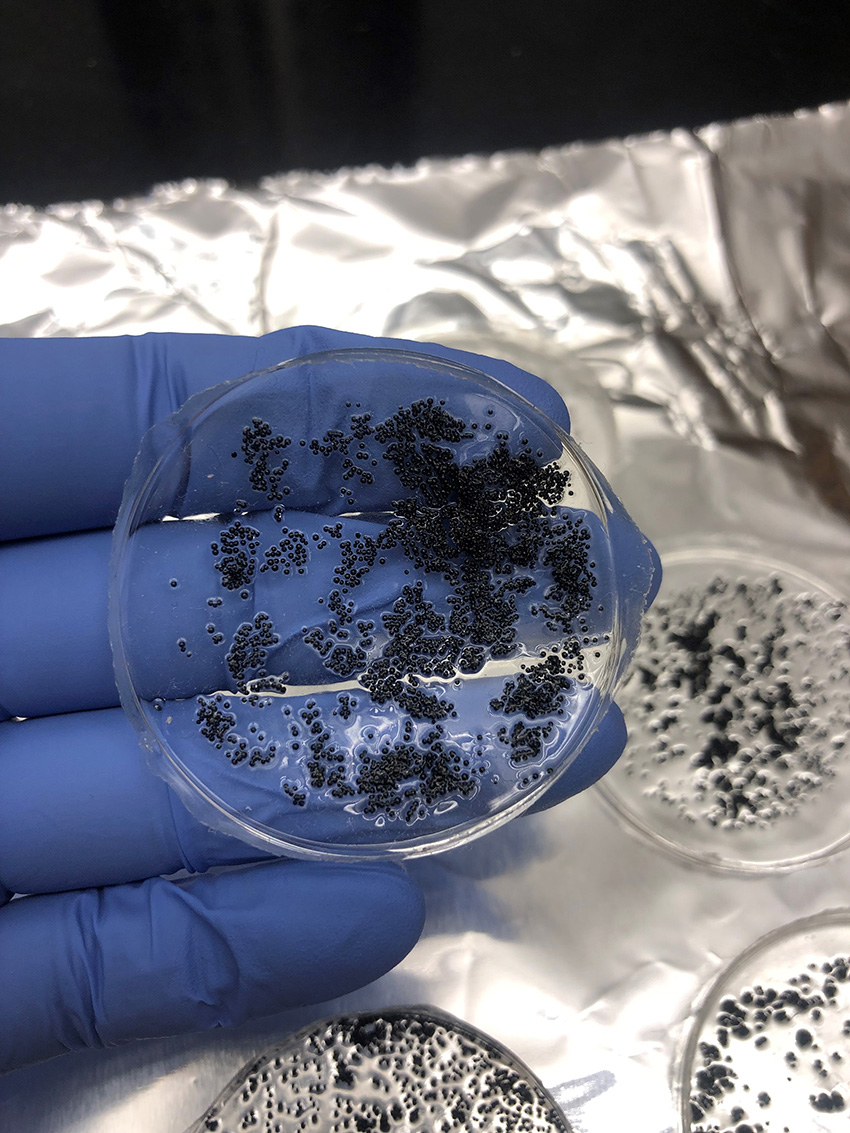

One promising assessment tool is passive sampling. Both Vlahos and Loretta Fernandez, Ph.D., a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northeastern University, are using this technique to “sniff” the water to determine not only the location of potential munitions, but also whether their chemical byproducts may be dangerous. According to Fernandez, researchers can place polymers in the water that have a specific affinity for the chemical they want to detect and then measure the signal over time.

“It’s a hands-off approach,” Fernandez says. But the benefit, especially in the ocean where currents and plumes can change, is that you are slowly collecting material over time, so if the chemical is there one day, but gone the next, it can be captured during the time it is there. “It allows us to find much lower concentrations of chemicals” when needed.

With passive sampling, Fernandez states, researchers can estimate how far certain munitions-related chemicals can travel before they transform into other, potentially more dangerous byproducts. This knowledge helps scientists see which of these byproducts may have longer lives than the original molecules, thus allowing them to determine which materials would be best for environmental cleanup measures. By better understanding how these different compounds degrade, scientists devise better mitigation strategies.

“We can use the passive samplers to tell us where the concentrations of chemicals are exceeding levels that might be dangerous to human or environmental health,” explains Fernandez.

While robotics and AI may get more attention for their cutting-edge technology, passive sampling, Vlahos says, is a “useful, inexpensive tool to help maintain safe water quality for communities.” But she believes even passive sampling technology will improve with time and assist with the global underwater unexploded ordnance problem.

“We’ll have better sensing methods so that we could have some kind of global array of these chemical sensors that will ‘go off’ like those we have for metals and radiation,” Vlahos says. “We will eventually make our way there. And passive samplers are a stepping stone.”

Kayt Sukel is a science and technology writer based outside Houston.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “Sniffing Out Underwater Ordnance.”