By Robert L. Reid

The Simone Veil Bridge in Bordeaux, France, was designed to be a public space as well as a river crossing. Its seemingly simple design belies a wide range of potential applications.

The new Simone Veil Bridge, which crosses the Garonne River in Bordeaux, France, is something of a contradiction in concrete and steel. Its architect, Netherlands-based OMA, intended the vehicular, public transit, and pedestrian crossing to challenge current trends in bridge design, which the firm argues too often feature an “obsession with bridges as triumphant feats of engineering or aesthetic statements.”

Instead, the Simone Veil Bridge “abandons any interest in style, form, and structural expression in favor of a commitment to performance and an interest in future use by the people of Bordeaux,” explains the OMA website.

Yet the bridge, dubbed “anti-iconic” by one of its architects, has attracted considerable attention for the simplicity of its design, which has been described as stripped down and clean, but also mundane and even boring. As a result, the crossing has become ironically iconic despite what its designers intended.

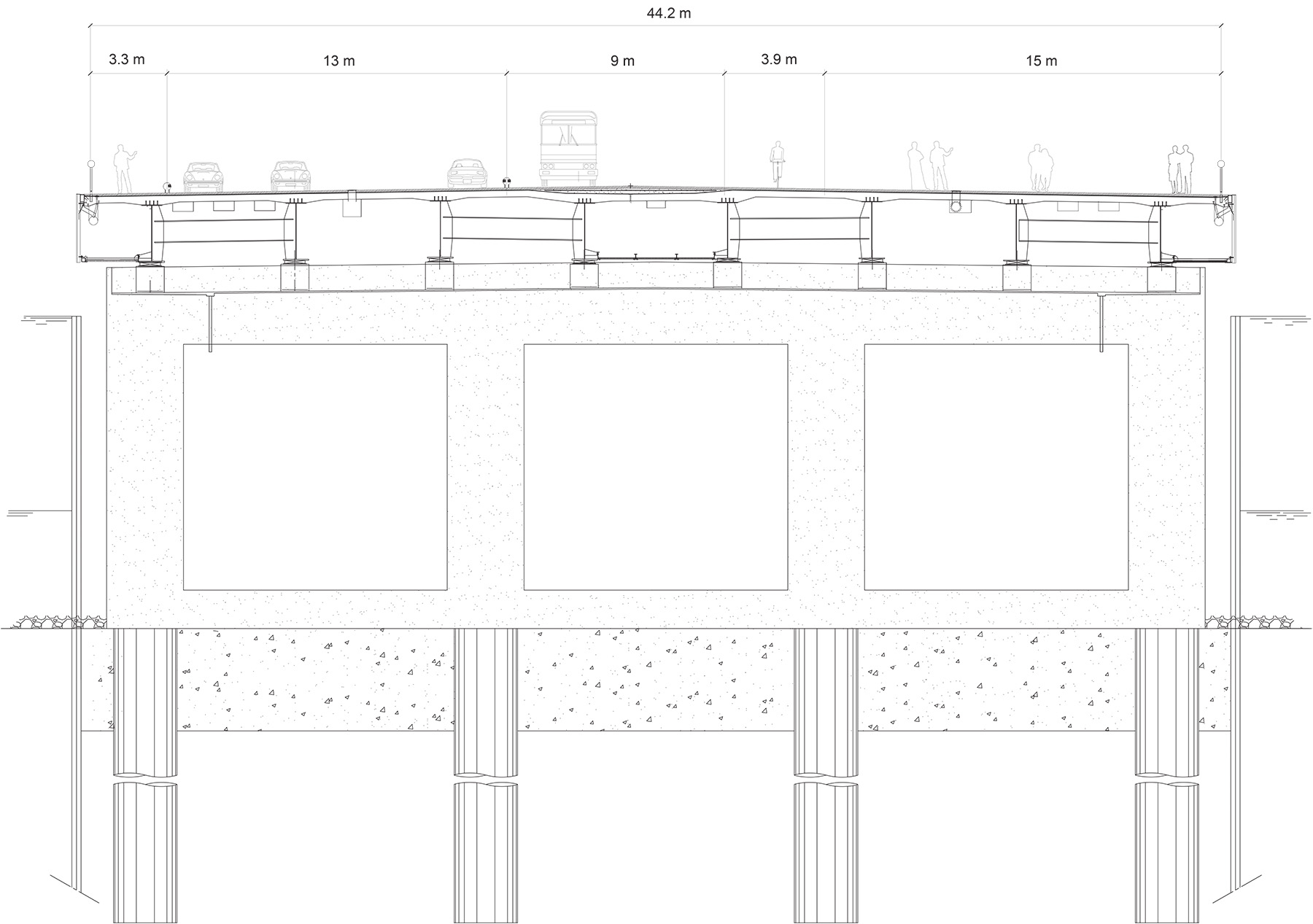

One thing that is definite about the Simone Veil Bridge is its size — especially in the transverse direction. At 44.2 m across, it features the widest concrete deck in Europe, a detail that is integral to the bridge’s purpose. More than just another way to cross from one side of the Garonne to the other, the bridge is also meant to be a public space that unites the neighborhoods on either bank of the river.

The great width of the bridge provides room for cultural or commercial events, including “farmers’ markets, art fairs, bicycle rallies, car club meetings, and festivals for music or wine,” explains OMA. In designing this 21st-century structure, OMA looked back to bridges of the past that served as “urban spaces in themselves,” including Venice’s Rialto Bridge, which dates to the 16th century, and 18th- and 19th-century iterations of Istanbul’s Galata Bridge, the firm notes.

Competing to cross

The project was designed for Bordeaux Métropole, which encompasses 28 municipalities in and around the city of Bordeaux, in southwestern France. The northward-flowing Garonne is a powerful, turbulent river, more than 500 m wide in places. Five other road bridges, as well as dedicated railroad bridges, cross the river within the area, but growth in the region led to congestion on those existing structures, according to the Bordeaux Métropole website.

A sixth road bridge had long been under discussion and was approved by the regional authorities in 2007. An extended planning and consultation phase followed, leading to an international competition in 2013. OMA, led by Pritzker Architecture Prize-winning Rem Koolhaas, won the competition, together with WSP Finland as structural engineers for the bridge superstructure.

After the competition, Egis joined the design team as structural engineers for the foundations and works supervision.

The project broke ground in March 2017, but roughly a year later, work came to a halt because of disagreements with the original main contractor. Following a public mediation process and the replacement of the original contractor, work resumed in spring 2020. In July 2024, the completed bridge opened to the public, with crowds gathering on the deck’s open spaces as well as on the new, tree-lined public areas and other amenities that were created on each bank of the river.

Public focus

The 549 m long Simone Veil Bridge was named for an influential female French politician and former president of the European Parliament who promoted women’s involvement in politics. It sits between the François Mitterrand Bridge to the south and the Saint-Jean Bridge to the north, connecting urban developments in Bordeaux and suburban Bègles on the left bank with the city of Floirac on the right bank.

The bridge is a continuous composite girder structure with nine spans. Its concrete deck is supported on eight adjacent steel girders paired with cross beams, notes Pekka Pulkkinen, WSP Finland’s project team leader.

Although the new crossing is expected to carry 30,000 motorized vehicles per day, the focus of the bridge is on public transit and so-called soft modes of travel, including bicycles and walking, explains Bordeaux Métropole. Toward that goal, the new crossing’s deck was designed with the two central lanes dedicated to public transportation. This space, 9 m wide, currently accommodates buses, but the structure can easily be adapted for tracks and a tram system, says Gilles Guyot, an OMA project manager. On the upstream side of the structure, there is also a 13 m wide space with four lanes of motor traffic and a 3.3 m wide pedestrian path along the outer edge.

The downstream side of the crossing features a 3.9 m wide lane for cyclists and a 15 m wide esplanade for pedestrians, especially for the aforementioned cultural events, gatherings, and other activities. Many of the railings or other barriers that separate the lanes, and even the lighting fixtures, are removable to increase the size of the potential event spaces.

Deep design

In addition to the powerful current, other site challenges included the relatively poor soil conditions in the riverbed, which featured a thick layer of alluvial deposits that required deep foundations to reach stable ground, explains Claude Le Quéré, the director of bridges and structures at Egis.

The foundation system features eight piers, each with a headframe resting on four columns that are 3 m by 3 m in cross section and supported on piles that extend 27 m deep beneath the riverbed. Originally, the design of the foundations had considered using five piles per row, each 1.60 m in diameter. In the end, the foundations were constructed with four 2.5 m diameter piles, one beneath each column, says Guillaume Danan, an engineer and project director at Egis. They are the largest diameter piles ever built in France, adds Le Quéré.

Because the river conditions also made traditional cofferdams a challenge, the design team opted to use temporary, watertight caissons integrated with each pile for the bridge’s foundations, allowing the work to be completed in the dry.

Another unusual aspect involved the square shape in cross section of the concrete piers. The hard angles of the piers were an aesthetic choice, Le Quéré says, and are protected against scour damage by prefabricated concrete casings. Gabion mats were also installed in the riverbed to protect the foundations against erosion, Guyot notes.

The columns are spaced approximately 10.3 m apart in each row, says Danan, while the rows are spaced roughly 64 m apart along the length of the bridge — except at each end, where the final spans are about 51 m long before landing on the concrete abutments. Although the Bordeaux region is not a high-seismicity zone, the bridge foundations were designed to withstand earthquakes and feature anti-seismic stops, which consist of reinforced-concrete blocks fixed to the supports for the deck to prevent movement during an earthquake, says Danan.

Using temporary platforms that extended into the waterway, the contractor worked from both banks simultaneously to erect the piers, leaving open the roughly 30 m wide navigation channel in the middle of the river, Danan says. The bridges on either side of the Simone Veil restrict the size of vessels that can pass under the new crossing to just small watercraft. Because the Garonne is a tidal river, the level of water beneath the bridge differs throughout the day, with a maximum clearance of roughly 11 m NGF. The term “NGF” refers to a network of altimetric benchmarks across France, with 0.00 NGF representing the level of the sea in Marseille, explains Guyot.

Composite structure

The superstructure of the bridge is composed of eight steel I-beam girders with a concrete deck slab that work together as a composite structure, says Pulkkinen. Key challenges during the project included optimizing the number of steel beams laterally and finding a construction method to launch the beams longitudinally over the piers, Pulkkinen notes.

The height of the main girders varies along the bridge longitudinally, starting at 1.15 m at the abutments and reaching a maximum of 2.25 m along the main spans. The girders had to be lower at the end spans to help provide adequate space beneath the bridge deck for pedestrian routes along the riverbank, Pulkkinen says. The main girders are braced by 850 mm tall cross beams that vary in spacing from 3.7 m to 5.6 m.

The thickness of the concrete deck also varies, from 250 mm to 355 mm, to provide the optimal structural economy, Pulkkinen says. An Egis video about the Simone Veil Bridge notes that it took two mobile crews more than nine months to complete the deck’s concrete. Guyot adds that the deck features a longitudinal slope of less than 4% to ensure universal accessibility to this new public space on the water.

The installation of the superstructure’s steel girders was also challenging, Pulkkinen notes. Varying in length from 16.8 m to 23.3 m, the main girder segments were welded in pairs into continuous sections, each roughly 100 m long. These sections were then pushed from the abutment on the right bank, out across the intermediate supports, and into their final positions.

The deck is supported on intermediate piers with elastomeric bearings. The end abutments also feature longitudinally sliding bearings and expansion joints.

Green surroundings

In addition to the nearly 25,000 sq m of usable space, the project also developed new public areas on each side of the river. On the left bank, for instance, some 570 trees, more than 4,800 shrubs, and 132,000 climbing plants, perennials, and other vegetation were planted, along with 2,200 sq m of lawn space, according to Bordeaux Métropole.

The right bank received 590 new trees, 470 shrubs, and 65,200 climbing plants, perennials, and other vegetation, along with 9,500 sq m of new lawn space. Both banks received an additional 30,000 sq m of new roadways and hundreds of new streetlamps. Several works of public art are also planned for the right bank.

To accommodate these changes, an existing roadway tunnel was demolished on the left bank, Guyot says, and various underground utilities were rerouted. New ramps and underground paths were created to provide access under the end portions of the bridge for pedestrians and traffic.

Intended to be a “living place,” the Simone Veil Bridge represents “the future of bridges in Europe,” which are trending toward modular, adaptable designs that accommodate multiple modes of transportation and uses, says Le Quéré. Moreover, it is an environmentally sensitive structure that promotes fewer emissions — via its support of pedestrians, cyclists, and public transit — while also requiring an estimated 59% less concrete and 54% less steel during its construction than comparable projects, the Egis video notes.

In addition to all the public attention the Simone Veil Bridge has received, the project also recently won the prestigious Équerre d’Argent “Silver Square” award, bestowed by French media groups, in the infrastructure and civil engineering works category, marking it as one of the best projects in France for 2024.

Apparently, this seemingly simple structure cannot help but stand out.

Robert L. Reid is senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

Project credits

Client

Bordeaux Métropole

Architect

OMA, Rotterdam

Structural engineer, superstructure

WSP Finland, Helsinki

Structural engineer, foundations

Egis, Guyancourt, France

Landscape design

Michel Desvigne Paysagiste, Paris

Civil works contractors

Bouygues Travaux Publics Régions France, Guyancourt, France, and Pro-Fond, Les Essarts-le-Roi, France

Steel structure contractor

Baudin Châteauneuf, Châteauneuf Sur Loire, France

Roads

Colas Group and its Aximum subsidiary,Boulogne-Billancourt, France

This article first appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “An Anti-Iconic Landmark.”