By Leslie Nemo

The concrete arch design, despite being built quickly, has helped Pennsylvanians travel longer than any other structure on-site.

Beginning in 1809, two towns in Pennsylvania — Columbia and Wrightsville — wanted a bridge across the Susquehanna River that kept them apart, impeding westward expansion. It took 121 years and five versions, but the communities eventually got a crossing that has endured. The present Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge, also known as the Veterans Memorial Bridge, turns 95 in September.

The 7,374 ft long structure avoided the pitfalls and adopted the successes of the river bridges that came before it. The final result was completed ahead of schedule and was paid off in less than 13 years. And although the bridge is set to close for extensive repairs and modernization in a couple years, it reached the rare and semi-mythical status so many drivers wish their own roadways could achieve: The bridge is toll-free.

In a way, the free stretch of highway over the Susquehanna River does not exist because of the towns at either end. The truth is the other way around. In 1733, John Wright, a Pennsylvania colonist and businessman, obtained a charter to operate a ferry at the site of the future bridge, a site — according to an August 1997 Historic American Engineering Record report about the bridge — that was a popular crossing spot with Native American communities moving east and west across the region. Wright’s Ferry, named after him, would eventually become the town of Columbia on the east bank.

Wright made the crossing even more popular “by constructing a road on the east bank of the river that connected to a post road between Lancaster and Philadelphia,” per HAER. His son John took the expansion even further when five years later he built a road on the site’s west bank (Wrightsville), linking the ferry route with roads that led to York, Pennsylvania, and to Maryland. “This network of roads crossing the Susquehanna at Columbia and Wrightsville formed part of the system that would become the Lincoln Highway in 1913, the first coast-to-coast automobile route.”

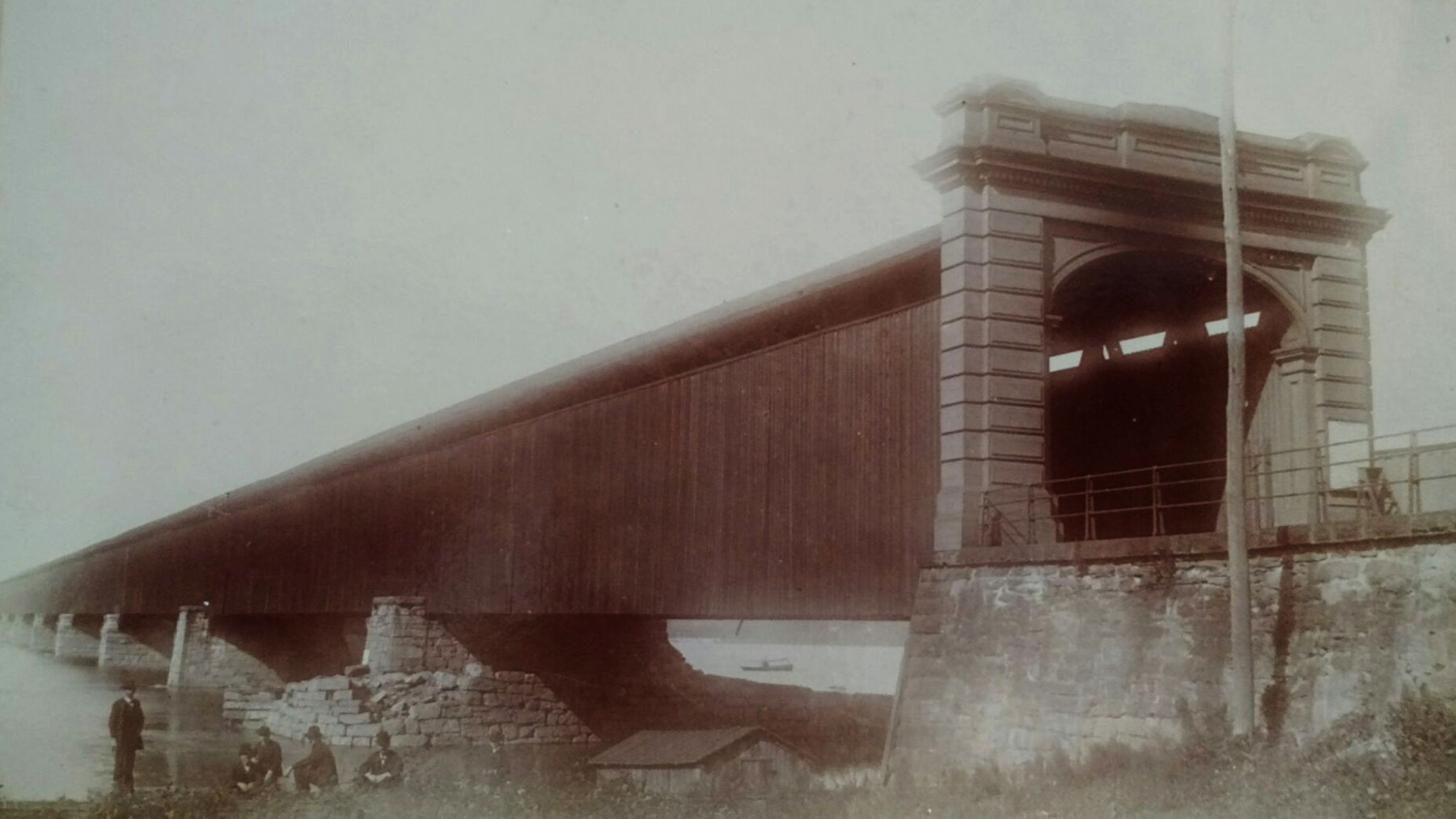

But back to the bridge: In 1809, the Pennsylvania General Assembly authorized the state’s governor to form a company to build the first of what would become a series of ill-fated bridges at the ferry-crossing site. The original 27-span covered bridge stood until 1832, when a flood of melted ice damaged the structure that spring. The replacement wooden structure went up in smoke in 1863, when Union soldiers lit the bridge on fire to keep Confederate troops from marching toward their goal: Philadelphia.

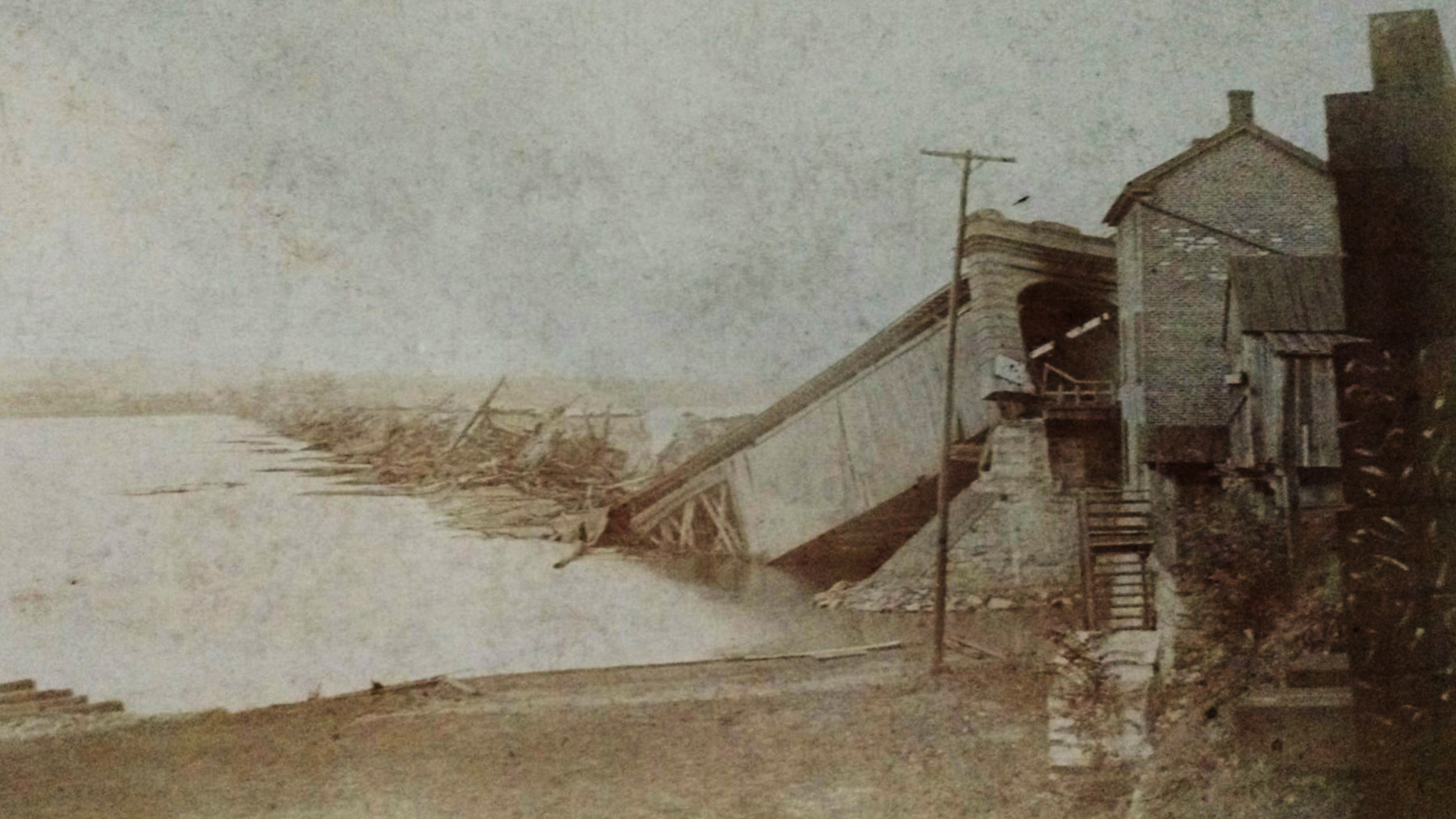

The third bridge, a covered wooden Howe truss with 29 spans, opened in January 1869. This structure met changing travel demands by carrying railroad tracks, but it too met an early end after a windstorm in 1896. It took only 21 days of construction for the Pennsylvania Railroad Co., the owner of the destroyed structure, to build a 27-span steel truss bridge. Dual construction teams worked at both ends of the bridge simultaneously, foreshadowing future building practices.

The final design of this fourth bridge had one major flaw: It could carry trains or cars, but not both simultaneously. The original design called for a two-deck bridge: the upper for vehicular traffic and the lower for railroad traffic. However, according to the HAER report, the upper deck was never built, so the lower roadway was shared by cars and railroads. While parts of the country with fewer cars might have had drivers who tolerated the long waits, the Lincoln Highway incorporated the bridge as part of its route when it opened.

By 1921, 6,000 cars relied on the river crossing daily. Toward the end of the decade, drivers often waited half an hour until a train had passed, according to Robert S. Mayo, P.E., M.ASCE, in his history of the bridge titled “The Fifth Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge,” which appeared in the Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society (1969, Vol. 73, 26-33). Incidentally, this fourth iteration remained in use by the Pennsylvania Railroad until 1958. It was then dismantled. The piers can still be seen north of the current bridge, acting “as icebreakers protecting the concrete bridge downstream. They also serve as a reminder of the other spans that stood at this crossing,” per the HAER report.

Meetings and suggestions about a new, car-only bridge cropped up on either side of the river through the early 1920s. Lancaster County, home to the city of Columbia, and York County, where Wrightsville sits, had chambers of commerce and residential automobile clubs interested in the possibility. The ultimate motivation to build the structure came through a bill proposed in Congress by U.S. Rep. W.W. Greist of Lancaster on Feb. 3, 1925, asking that the Susquehanna Bridge Corp. be allowed to build a privately owned toll bridge.

“From this point, and until the matter was finally decided two and one-half years later, the Chambers of Commerce and the Automobile Clubs of Lancaster and York counties accepted the burden of leadership,” wrote L.W. Newcomer in “A Prologue to the Construction of the Fifth Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge,” which was published in the Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society (1971, Vol. 75, 119-124).

Only 10 days after the first bill proposal, Congressman S.F. Glatfelter introduced another — this one asking consent for Lancaster and York counties to build a “publicly owned toll bridge,” according to Newcomer. County residents supported this second option in a ballot measure that November, in part thanks to campaigning from the Lancaster Automobile Club and the Chamber of Commerce.

Greist introduced a new bill in 1926, this time asking for a publicly owned bridge, and it was signed into law. A lawsuit from the Susquehanna Bridge Corp., which claimed that the construction of a publicly owned bridge was unconstitutional, delayed construction long enough that the federal legislation authorizing the public work in 1926 had to be re-signed in January 1928, but the new Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge was finally in progress.

Also in 1928, the Joint Board of Toll Bridge Commissioners formed to work on the structure — dubbed the Lancaster-York Intercounty Bridge — chose James B. Long as its engineer. Of the two designs (concrete or steel) that Long offered, the commission preferred the concrete version, and on April 26, 1929, it chose the Wiley-Maxon Construction Co. and its $2.484 million bid for the job. Its task was to build a reinforced-concrete bridge with 29 piers and 28 185 ft long spans carrying a 38 ft wide roadway and a 6 ft sidewalk, according to Mayo.

G.W. Maxon, a former civil engineer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Glen Wiley were based in Dayton, Ohio. Wiley was the inventor of the Wiley Whirley, a steam-operated gantry crane with an 85 ft long boom. A number of them made their way into the construction process because Wiley and Maxon opted to build the bridge with two teams operating from either side of the river. The contract was signed on May 9, 1929, according to the January 1930 Construction Methods article “Huge, Steel Arch Centers Moved as Units in Rapid Construction of 48-Span Intercounty Concrete Highway Bridge Across the Susquehanna River.”

First, to keep costs down and manage traversing a river that was more than a mile wide, construction began with a “wood pile construction trestle” extending 5,600 ft across the water, according to the Construction Methods article. The trestle carried three sets of rail tracks — one for carrying gantry cranes, and beneath it, two for hauling materials via gasoline-powered “dinkies.” The trestle wood, shipped in from Oregon, added up to a million board feet of lumber.

Next came the assembly of two identical construction sites on either side of the river, each with its own concrete mixing plant, trio of Wiley Whirleys, carpenter shop, and more.

Maxon and Wiley wanted to make enough progress on the permanent structure so that the trestle could be dismantled before the river froze during the winter of 1929. For their goal to be met, workers had to complete construction of all the piers in the Susquehanna and at least 18 of the 28 triple-arch spans over the water. Construction continued 24 hours a day in two 11.5-hour shifts to make this happen.

Each of the 29 river piers required an Ohio River-type cofferdam. Introduced around the start of the 20th century, this type of cofferdam was thought by the Corps to be more affordable than other designs. For this project, once the water was pumped out of the cofferdam, workers dug 2 ft into the bedrock for the pier foundation. According to HAER, “The Susquehanna’s shallow waters made this process easier, as the piers could be anchored in the bedrock that lay just a few feet under the river’s surface.” The first concrete was placed June 12, and the last river pier was finished September 14.

With some of the piers in place, workers could move on to the trio of parallel arch ribs making up each span. The construction tactic relied on 10 steel “centers,” a term Mayo, who was the field engineer for the Blau Knox Steel Co. that produced the equipment, used to describe the structures. The centers were pairs “of steel arch truss ribs with their footings tied together by a pair of horizontal steel tension members.

Wood lagging serving as the bottom of the arch form is blocked up from the top members of the steel ribs at the panel points. Side forms are placed as built-up units,” per the Construction Methods article. These centers were used “for concreting the three-rib arches spanning the 185 ft distances between pairs of river piers.”

The steel centers were supported by “vertical steel suspender bolts, 3.5 in. in diameter, threaded at their ends and hung from steel channel yokes seated on the tops of the concrete stubs of the arch ribs. Each steel center, with forms, weighs 100 tons,” according to the Construction Methods article.

“ ... After the concrete had been poured and achieved sufficient strength (7 days), (the steel centers) were slid sideways 16 feet and spotted to catch the second rib of that span,” wrote Mayo in his bridge history. Once all three arches for a span were completed, the steel centers traveled toward the center of the bridge on special train cars traveling the trestle tracks.

Maxon and Wiley met their cold-weather deadline: With nine spans concreted on each side of the river and the steel centers in place for 10 more, the trestle could be removed. The centering for the remaining spans could be installed by the Wiley Whirleys operating on tracks laid on the previously erected bridge.

Some of the speed at which this mile-long bridge came together was due to the steel centers, according to the HAER report. But there were a couple other motivating factors at play. The teams working from either bank were “in friendly competition,” according to Mayo. Potentially more important, the contract between Wiley-Maxon and the commissioners included a $400 bonus for each day the project was completed early. When accepted as complete on Sept. 28, 1930, the bridge was 140 days ahead of schedule.

Drivers were quick to pay the 25-cent toll to cruise across the train-free bridge, leading the counties to collect approximately $1,200 per day, according to Mayo. On Jan. 31, 1943, the bridge, having been paid off, became toll-free.

The Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge and all its components, including 101,000 cu yd of concrete and 7,991,000 lbs of reinforcing steel, have needed mostly minor repairs over the decades. However, in June 2023, a routine inspection by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation showed more advanced structural issues, namely in the “multiple primary load-bearing members across the bridge,” according to a report from PennDOT. The agency determined that the bridge will need to be closed to vehicles for about three years of a five-year repair plan that will kick off in 2027. When completed, the bridge will also be safer for pedestrians and bicyclists, the department said.

If the repairs can at least double the lifespan of the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge, then they will help preserve the structure that turned around the luck of the Susquehanna River communities. As Newcomer stated, funding and construction began before the stock market crash of 1929 that started the Great Depression. “Had it not been so — who can tell? — the old, narrow, inconvenient railroad bridge may have remained the only Columbia-Wrightsville crossing for another seven years — or more.”

In 1984, the bridge was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

Leslie Nemo is a journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, who writes about science, culture, and the environment.

This article first appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “The Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge That Endured.”