"I grew up in a South Asian household, and I think a lot of cultures will be able to relate to this, especially as an immigrant," Ahmed said.

"When you’re an immigrant and you come from certain countries or regions of the world, at least for me, you’re not just representing you or your family anymore, right? You’re representing every person who would love to be in the position you’re in with the opportunities you have.

"Because of that, there’s an expectation of excellence that’s inherently built into whatever you do. And that can be a lot. It can be a lot to navigate for a lot of people, including me.

"But I look at it as a responsibility. I want to maximize anything I can achieve out of this opportunity I was given by my parents when they emigrated from Bangladesh."

Ahmed is the middle child of three. His parents – father Sabur and mother Fatima – encouraged the kids to focus on academics from a young age.

"My mom played a massively important role the whole time, believing in me when I didn’t even necessarily believe in myself," Ahmed said, "So a lot of credit can be attributed to my mom as well for anything I’ve achieved."

Sabur was particularly keen that maybe one of his children might be an engineer someday. It was a career path he liked but wasn’t able to pursue when the family left Bangladesh.

"He’s had some tough times, like when we first moved to New Zealand, he worked at a gas station for a couple of years, making effectively minimum wage and trying to raise a family of five," Ahmed said. "So you can imagine some of the conditions we were living in. It wasn’t a terrible life. We had food on the table. But it wasn’t an affluent life when we emigrated.

"He had to work hard and didn’t want his kids to struggle. And he thought civil engineering would be a good route."

The middle kid made good on the idea, and Ahmed excelled as a geotechnical engineer in Vancouver, rising to chair of the Vancouver Geotechnial Society. He also helped start a national mentorship program and a webinar series for the Canadian Geotechnical Society Young Professionals Committee.

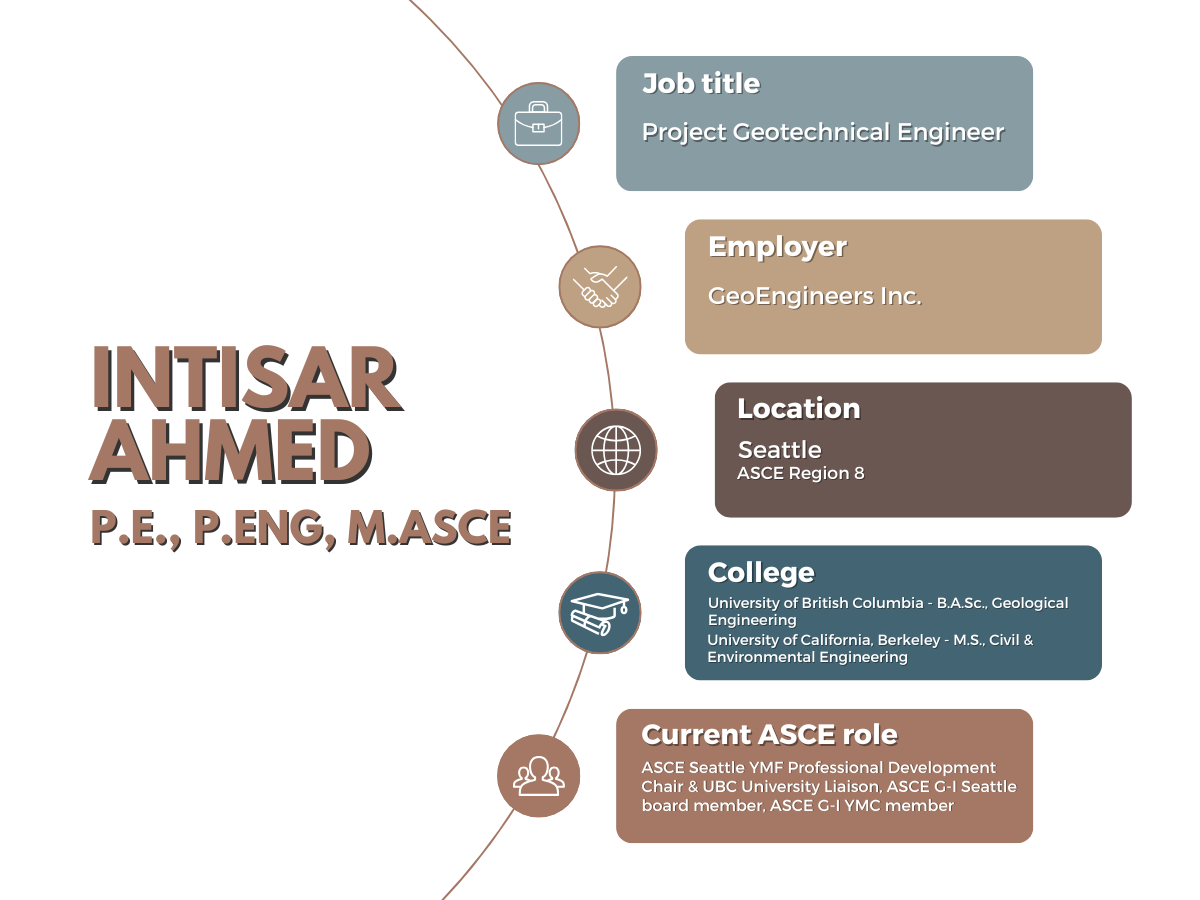

Last summer, he took a new job and moved to Seattle, where he already has made major contributions to ASCE, organizing technical and professional tours for the Seattle Section Younger Members Forum and bringing his CGS volunteering experience to the recently formed ASCE Geotechnical Institute Younger Members Committee.

It's a busy and accomplished life – much to the joy of his proud parents.

"It’s not often that we with Asian parents always hear that 'I’m proud of you,'" Ahmed said. “But I heard that from my father when I became licensed as a professional engineer. I know that meant a lot to him.

"He and my mom are both cheering me on."

ASCE has honored Ahmed as a 2025 New Face of Civil Engineering. He recently spoke with Civil Engineering Source about his career.

Civil Engineering Source: What is the one accomplishment or aspect of your career you’re most proud of?

Intisar Ahmed: I think the most rewarding aspect, when I look back on the last five years or so, has been the projects and the impact that I know my projects have had on the community. That’s the overarching thing.

It’s not even necessarily the big headline projects that are worth a billion dollars or anything like that. Some of the most rewarding projects I’ve worked on have been schools, where it’s just portable building additions to existing schools to help bolster their capacity.

Everything from schools to flood protection systems to a church building to major highway projects. I feel a real sense of accomplishment and pride.

And it helps a lot when it’s in the area you grew up in. So for me, I grew up in Greater Vancouver, Canada, and the first five years of my career, I worked on projects there. I’m starting to see some of the projects that I’ve worked on being constructed.

When I look back, that’s what I’m going to remember, I think, more than any other personal or individual accomplishment – the real, tangible projects that are benefiting people.

Source: How did you get started doing so many volunteer activities?

Ahmed: I learned early on that your network is your key throughout your whole career.

It’s not necessarily only what you know and what you can do, but there’s an aspect of who you know. That’s something I’ve put a lot of emphasis on in my career.

I’m a first-generation engineer. My parents are not engineers. I don’t believe there’s any engineering background in my family prior to myself. So, I was really starting from scratch. I did everything I could to look up these opportunities and organizations.

For instance, in Canada, at my very first internship I was given advice to attend the VGS’ local events. And initially, I thought, "Oh, I won’t understand anything. They’re talking about technical topics with professionals who know what they’re doing, and I’m just some 19-year-old second-year student who has barely been in the field."

But I thought, "Hey, why not? I’ve got to build my network somehow." So, I went, and I kept going, and I started putting my hand up for opportunities.

And the group kept encouraging me to stay involved, kept giving me more and more responsibility.

Last year, I ended up becoming the chair of the Society. So it was a long progression in my short career. That’s how I got started with, let’s call it, professional volunteerism.

Source: But is there something about you, a certain trait or experience, that has made you a leader in these organizations? Not everyone would do that. A lot of people need that structure to already exist for them to find their way in. It seems like you’re somebody who can create new things that aren’t there.

Ahmed: Right, there’s a bit of both. I mean, I totally empathize with those who need the structure and need something to build off of.

And I wouldn’t call myself a trailblazer or anything like that. But someone’s got to do it, right? And if you’re talking about a trait specific to me, I’d like to see myself as someone who really likes to take ownership of everything that I do. I think that’s probably my greatest asset.

If there is a task to be done, like starting a mentorship program or setting up in-person networking events or whatever it is, that’s something I own. It needs to be done to a standard that I’m happy with. I don’t ask anyone to do things that I wouldn’t do myself. So, it’s that willingness to put my hand up, take ownership of whatever task it is, and run with it.

And as far as the initiative goes, I think I’ve always naturally had these crazy ambitions or ideas. I don’t initiate or lead every idea that comes into my head, but some of them aren’t half bad. [laughs]

So I do try to make the effort when there’s a good idea that I think will work. We just build it from there, and it’s not always a success. Sometimes you learn some lessons and just move on. But the key is to really take ownership and care about whatever it is you want to do, and trust that if you do that, then usually it will work out.

Source: What kind of impact would you like to make on the profession?

Ahmed: I think there are two things.

One is how many people I can help with the work that I’ve done; like directly as far as end users of projects I’ve worked on.

That’s an impact that civil engineers have constantly. That’s not unique to me. We’re privileged to be in a profession that has a positive impact on society.

But if you go beyond that, there’s the aspect of mentorship. If I’m able to impact somebody else’s career – at least one person – then I will have done some good in some way to pay it forward. Then they’ll impact somebody else, and it goes on and on and on.

I’m a result of a lot of mentors, and hopefully I can be someone like that for somebody else.