As the backlog of bridges needing inspection or repair across the U.S. reaches a critical point, technological improvements have never been more important.

ASCE’s 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure found that 42% of the country’s 617,000 bridges are at least 50 years old – with an average age of 44 – and more than 46,000 are structurally deficient. According to the report card, “a recent estimate for the nation’s backlog of bridge repair needs is $125 billion.” (The 2025 report card will be released this month.)

Further reading:

- Comparing bridge inspection policies to assess data quality

- How engineers saved Washington, DC’s, iconic Arlington Memorial Bridge

- In Seattle, cracks strike side-by-side bridges simultaneously

Inspections usually focus on the steel beams that support the bridge deck. Bridge inspectors “use ultrasound to measure the thickness of the beam,” said Sergey Sukhovey, co-founder of Artec 3D, a developer of advanced 3D scanning hardware and software. “And by making an analysis of these measurements, they calculate the residual load capacity of the beam itself and then the overall load capacity of the bridge.”

But ultrasound may be too slow and imprecise to tackle the backlog of bridge inspections. “If you hold the mic at the wrong angle or slightly off, or you have too much ultrasonic gel on it or not enough, you can get different readings,” said Matt Weidele, P.E., a bridge load rating and overload engineer at the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. “The same inspector could put that mic up to the beam web and get three different readings on three consecutive touches to the beam based on how he’s holding the probe.”

Ultrasound sensors also must touch the bridge beams, meaning inspectors find themselves in all sorts of challenging positions, often hanging from a bucket.

Meanwhile, countless steel bridges are slowly deteriorating, due in large part to corrosion, which weakens a bridge’s load capacity over time. Corrosion is a “very nonuniform phenomenon,” says Simos Gerasimidis, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a visiting associate professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“So the first line of attack of the problem was to take out some of the real bridges from the field and bring them to our lab for testing,” Gerasimidis said. His research team at UMass obtained beams – courtesy of MassDOT – from bridges slated for demolition. “We tested the bridges mechanically to find their remaining capacity, but in the process we also documented corrosion using ultrasound sensors (conventional method) and laser scanning (the new method).

“This comparison led to finding that laser scanning can be a game changer.”

The research team developed new guidelines to better predict load capacities but realized that it was “challenging for inspectors to be able to document this problem adequately,” Gerasimidis added.

The team needed technology more precise than ultrasound.

The speed and convenience of 3D scanning

So Gerasimidis turned to colleague Chengbo Ai, also an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at UMass, who is an expert on scanning technologies. The Gerasimidis research lab at UMass Amherst worked with a wireless 3D scanner from Artec 3D, the Artec Leo, which promised 0.1-millimeter accuracy and capture speeds of up to 35 million points per second.

Artec got its start building 3D scanners for biometric recognition in the late 2000s, then expanded to other fields, including architecture, engineering, archaeology, computer graphic animation, and health care. Its devices allow users to walk around an object of interest and create a 3D representation from multiple vantage points.

The current flagship scanner, Artec Leo, which is about the size of two or three digital single-lens reflex cameras, creates a wire mesh representation of the object it is scanning. 3D scanning can calculate a point cloud consisting of hundreds of thousands of data points across three dimensions. This is far more information than ultrasounds can provide.

AI is a core component of the firm’s 3D scanning software, Artec Studio. By activating HD Mode, Leo owners can sharpen the resolution of scans and boost detail capture with AI. In data processing, the AI-powered autopilot also helps automate tidy up. Artec’s latest release even includes AI Photogrammetry for creating textured models from any photo or video set.

The real work, though, is not using a 3D scanner but properly processing the information it collects. The data points a scanner generates do not on their own equal “structured meaning,” Ai said. “Without processing the data, each point doesn’t necessarily know how to link with the other points” to create meaningful information, such as the severity of the corrosion or the residual thickness of the beam.

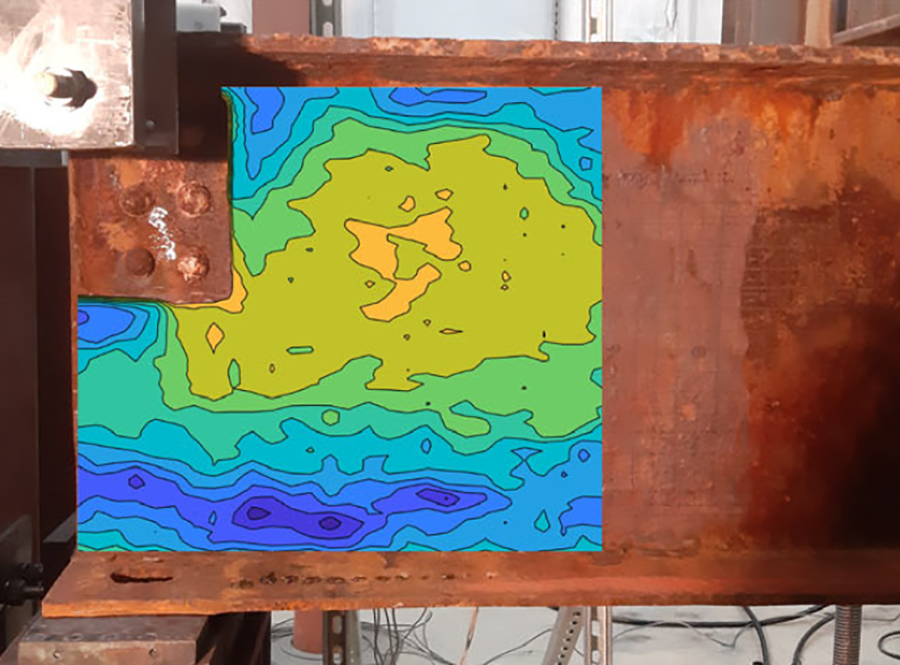

The lab fed data from the Artec scanner – as well as from other sources such as lidar – into its own data processing algorithm and then into a Dassault Systems’ Abaqus finite element analysis software for structural analysis. Taking scans from several beams along with their experimental capacities found in the lab, the research group developed computational models that could predict which beams were likeliest to lead to a bridge failure.

Testing in the real world

3D scanning offers potential advantages over inspecting bridges with ultrasound. Measurements can be made faster, and the user experience is simpler and more reliable. “Rather than painstakingly capturing one data point at a time, 3D scanning allows you to capture thousands in minutes,” Sukhovey said. “You can also work under direct sunlight.” Time saved during inspection can mean less time bridges are shut down for inspection.

Gerasimidis adds that 3D scanning allows inspectors to work from up to a meter away, saving time and effort for inspectors getting into and out of buckets to inspect beams.

Documentation is also better with 3D scanners than with ultrasound.

“The beauty of this methodology is, compared to ultrasound, we document it,” Ai said. “If you imagine one sample point for that bridge, nobody can know in two years where the sample point’s coming from. However, with this kind of scan, you would have a more comprehensive one to go together with the inspector’s pictures and everything, and then they have a direct linkage with their old image pictures with a three-dimensional scan.”

Ai believes this will become the norm for bridge inspection in the coming years.

3D scanners have been deployed in a few bridge inspections already. Artec notes that rusting panels on San Francisco’s Richmond-San Rafael Bridge needed to be replaced. But up until a few years ago, there were no drawings or measurements available, so the existing panels had to be accurately scanned – including the precise location of 250 rivets per panel – to design new panels.

To make matters worse, the panels were part of a busy bridge spanning 185 feet over the windy San Francisco Bay. Artec’s handheld scanners enabled crews to scan the panels over several months during tight windows when they were allowed onto the bridge. New panels were then fabricated and installed within eight months. Artec estimates the work was 75%-90% faster than if traditional inspection tools had been used.

In 2023, bridge inspectors working in Springfield, Massachusetts, found beams on a bridge carrying a section of Interstate 91 had pitting along the base of the web. MassDOT asked UMass researchers – the department has provided support to the lab for years – to take scans along multiple beams in an attempt to improve data quality. UMass then used computers to filter through millions of data points to create a model of areas’ average section loss.

“We simplified it down to a measurement that our load raters could then take and plug into our beam end equations,” Weidele said. This produced a more accurate result than simply assuming the maximum pit depth was uniform along the whole beam. It was the difference between getting back a potential “close the bridge” calculation to a more precise figure. “It made a drastic improvement,” he said.

Gerasimidis doesn’t expect this technology to be applied to every bridge. Many bridges can be easily inspected by eye. But for borderline cases, where a subtle analysis may determine whether a bridge is still safe to use or needs to be repaired or closed, he says the technology could be useful. “That’s where we see this being very useful,” he said.

Weidele also notes that this technology may not be needed on routine inspections and that its success still depends on inspection teams having the back-end data analysis support to “correctly interpret the scans and not have massive errors in the data.” Still, he noted that “what it does is (it) saves time from the inspection personnel needing to set up grids and measure every 1 inch on center to get detailed measurements when there’s a concern with an area of deterioration.”

According to Artec, overall, lidar systems like the Artec Ray II are highly popular in the infrastructure space. But Leo is bringing next-level maneuverability to inspection. The UMass Amherst project marks the third U.S. initiative of its kind that Artec 3D has facilitated. Moving forward, other local authorities in Massachusetts are also considering its technology for further predictive repair initiatives.

Massachusetts has not yet committed to 3D systems. Other states are exploring the technology. Last year, the Connecticut Department of Transportation used scanners on a damaged portion of a bridge to collect information to assist with analysis and repair details.

“We have not purchased any 3D scanners to date, but we are still considering,” said Keith Gaulin, P.E., deputy chief engineer for bridge engineering for the Rhode Island Department of Transportation. RIDOT inspects about 400 bridges a year. “The technology does seem to be very useful and promising but seems to have some limitations for field applications and postprocessing of the data,” Gaulin added.

Gerasimidis notes that 3D scanners are not intended to replace bridge inspectors or load capacity engineers – only to provide relief to a backlog that he describes as massive. (Massachusetts alone has thousands of bridges.) “Whenever I talk about this, I encourage the person I’m talking to: ‘When you go home, try to look at the bridges that you go under. I bet half of these have corrosion. They’re everywhere,’” he said.