National Transportation Safety Board

National Transportation Safety Board

In March 2024, Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapsed after being struck by the Dali, a 984-foot cargo ship that lost power on its way out of the Seagirt Marine Terminal. Thanks to a nearby camera livestreaming the comings and goings of ships in the area, millions watched this mainstay of Baltimore’s skyline quickly disintegrate into the Patapsco River. Tragically, the collapse resulted in six casualties.

It wasn’t the first time a U.S. bridge suffered this fate. And, unfortunately, new research warns, without decisive action it might not be the last.

Further reading:

- Shock, heartbreak fill civil engineering community as tragedy strikes iconic Baltimore bridge

- New model helps ships recognize, avoid potential port accidents

- 5 things you didn’t know about the Tacoma Narrows Bridge

Matthew Yarnold, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE, is the director of the Advanced Structural Engineering Laboratory at Auburn University, whose research focuses on bridge engineering. He said the Baltimore catastrophe was reminiscent of Florida’s Sunshine Skyway Bridge disaster in 1980, when high winds caused a large freighter, the Summit Venture, to veer off course and hit the bridge. About 1,200 feet of the bridge collapsed into Tampa Bay after the hit, resulting in 35 deaths.

“Unfortunately, this is very much a case of history repeating itself,” Yarnold said. “Since the 1980s, we’ve seen an ever-growing increase in ship traffic and ship sizes across the globe. This significantly changes the potential impact forces and potential consequences of a collision.”

To understand the risk of a ship strike occurring, Michael Shields, Ph.D., M.ASCE, an associate professor in Johns Hopkins University’s department of civil and systems engineering, and colleagues last month published a report quantifying the potential risk of ship collisions at major bridges across the U.S.

“My research is in risk, reliability, and probabilistic modeling. When the Key Bridge collapsed, it was only natural for my group, as well as the community at large, to ask: What were the chances of (this collision) happening?” he explained. “How likely is it that something like this will happen to another bridge somewhere else in the United States?”

Developing a risk model

Shields and colleagues created a risk assessment model based on three distinct components: the amount of large vessel traffic that goes under each bridge, the probability that a vessel will aberrantly go off course, and the risk – if the vessel does aberrate – of it colliding with the bridge. Shields said that traffic data is abundant, as the Coast Guard automatically collects identification system data from ships in U.S. waters.

“Every ship in American waters is communicating its status, its location, and its heading to the Coast Guard every minute,” he said. “When you compile that over a decade and a half, you are talking about hundreds and hundreds of millions of data points. We cross-referenced that data with information from the (Federal Highway Administration’s) National Bridge Inventory so we could see every time one of these large ships passed under a bridge over the past 16 years.”

With that data in place, the research team then tried to mine the Coast Guard’s list of recorded aberrancy events, when large vessels deviated from course. One challenge, however, is that many events, if they do not result in collisions or other issues, are not recorded.

“There are so many reasons why a ship could aberrate,” Shields said. “It could be pilot error, it could be weather, it could be the currents, or any of a number of other factors. … In the absence of (complete data), we used the base aberrancy rate from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.”

Using that data, the researchers were then able to estimate the probability of collision for dozens of bridges across the U.S.

Shields said the group hypothesized the probability of collision would be “higher than we would want it to be.” Even so, he added, he was surprised that it ended up being as high as it was for so many bridges.

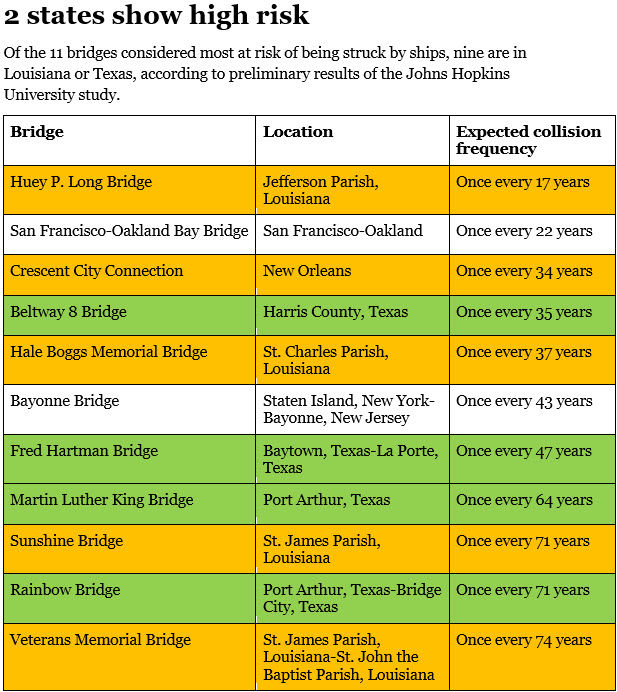

For example, the model notes that the Huey P. Long Bridge in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, has a probability of a collision every 17 years; the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge has a probability of a collision every 22 years; and the Beltway 8 Bridge in Harris County, Texas, has a risk of a collision every 35 years.

“We only looked at the probability of collision, not collapse,” Shields said. “But it’s important to recognize that these are not exceedingly rare events. This is something we need to be designing for.”

Assessing for strike risk

Abieyuwa Aghayere, Ph.D., P.Eng, F.ASCE, a professor of civil, architectural, and environmental engineering at Drexel University who focuses on bridge design, said the results of the Johns Hopkins study did not surprise him.

“I had a student do some research not long ago, and he found out from the Coast Guard data that there have been more than 2,000 ship engine failures in the past 14 years within 1 mile of the U.S.,” he said. “When the engine fails, the water is going to take the ship where it wants to go – and we need to protect the bridge piers.”

Yet, Yarnold said, there is only so much that bridge designers can do without proper funding. He said many of the bridges listed in the Johns Hopkins report are older and already require retrofitting for other needs, like protection against earthquakes or hurricane storm surge.

Federal funding for infrastructure was a major theme of ASCE’s 2025 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, which assigned a grade of C to U.S. bridges and cited a $373 billion funding gap over 10 years to bring them to a state of good repair.

“If we had infinite resources, we could upgrade all these bridges. But without the right funding and resources, it becomes a bit of a balancing act,” Yarnold said. “The risk of vessel collision needs to be weighed against all the other risks. Given that there’s no ribbon cutting for a retrofit, typically, we need more bridge owners to take a risk-based approach to figure out where it makes the most sense to put their resources to do an upgrade.”

With a recent National Transportation Safety Board report noting that the Key Bridge was almost 30 times more vulnerable than what bridge design standards currently allow for, Aghayere added that there’s no time to lose – and risk assessments may identify investments that are far less expensive to cities and communities in the long run.

“You can’t put a cost on the loss of life from a bridge collapse,” he said. “But the cost of rebuilding the Key Bridge, which will be about $2 billion, and the associated costs of disruption in the area while it is being rebuilt, is very expensive. In comparison, protecting the two major piers would have only cost them maybe $100 million. The cost of retrofitting is much smaller.”

For example, Shields’ model projects that the Delaware Memorial Bridge, which spans the Delaware River, has a probability of a collision every 129 years. But given the larger sizes and faster speeds of today’s vessels, the Delaware River and Bay Authority announced it would invest in preemptive protection measures in 2023, more than a year before the Key Bridge collision.

“They are building protective dolphins around the bridge piers in navigable waterways,” Aghayere said. “It’s costing them more than $90 million. But they looked at it, they assessed it, and believe, with this investment, they can protect the piers, and the bridge can still serve for many years.”

Ultimately, Shields hopes more bridge stakeholders will undertake risk-based assessments to better prioritize maintenance and upgrades. He reminds bridge engineers that in the aftermath of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge collapse, it was highly recommended that older bridges be assessed in such a manner. But because it was a recommendation, not a mandate, few organizations did so.

“If there’s any lessons learned, I think these kinds of risk-based assessments are essential, and they should be mandated,” he said. “And I hope that some agency at the federal level will not only say, ‘This needs to happen,’ but will provide the resources to make sure it does happen.

“If the risks aren’t assessed and mitigation measures aren’t put in place, we will see another collision. It’s just a matter of time.”