Courtesy of DEEP

Courtesy of DEEP  Courtesy of DEEP

Courtesy of DEEP Living and working for extended periods in underwater habitats is not by itself anything new. The French aquanaut and oceanographer Jacques Cousteau did it first in 1962 with his Conshelf habitat, which was placed off the coast of Marseille, France, at a depth of 33 feet underwater.

Cousteau experimented with larger habitats at greater depths throughout the 1960s, as did the U.S. Navy with its SEALAB program. Since then, other underwater habitats have been constructed at or proposed for various sites and varying depths around the world.

The earliest habitats featured fixed designs that could not be changed over the life of the structure. More recently, though, several projects have been proposed with modular designs that can be reconfigured to meet changing needs and changing locations, including Proteus, led by Fabien Cousteau, a grandson of Jacques Cousteau.

Further reading:

- Underwater engineering offers the chance to harness ocean resources

- Swiftwater rescue training facility coming to Houston

- Subsea telecom cables could detect earthquakes, tsunamis

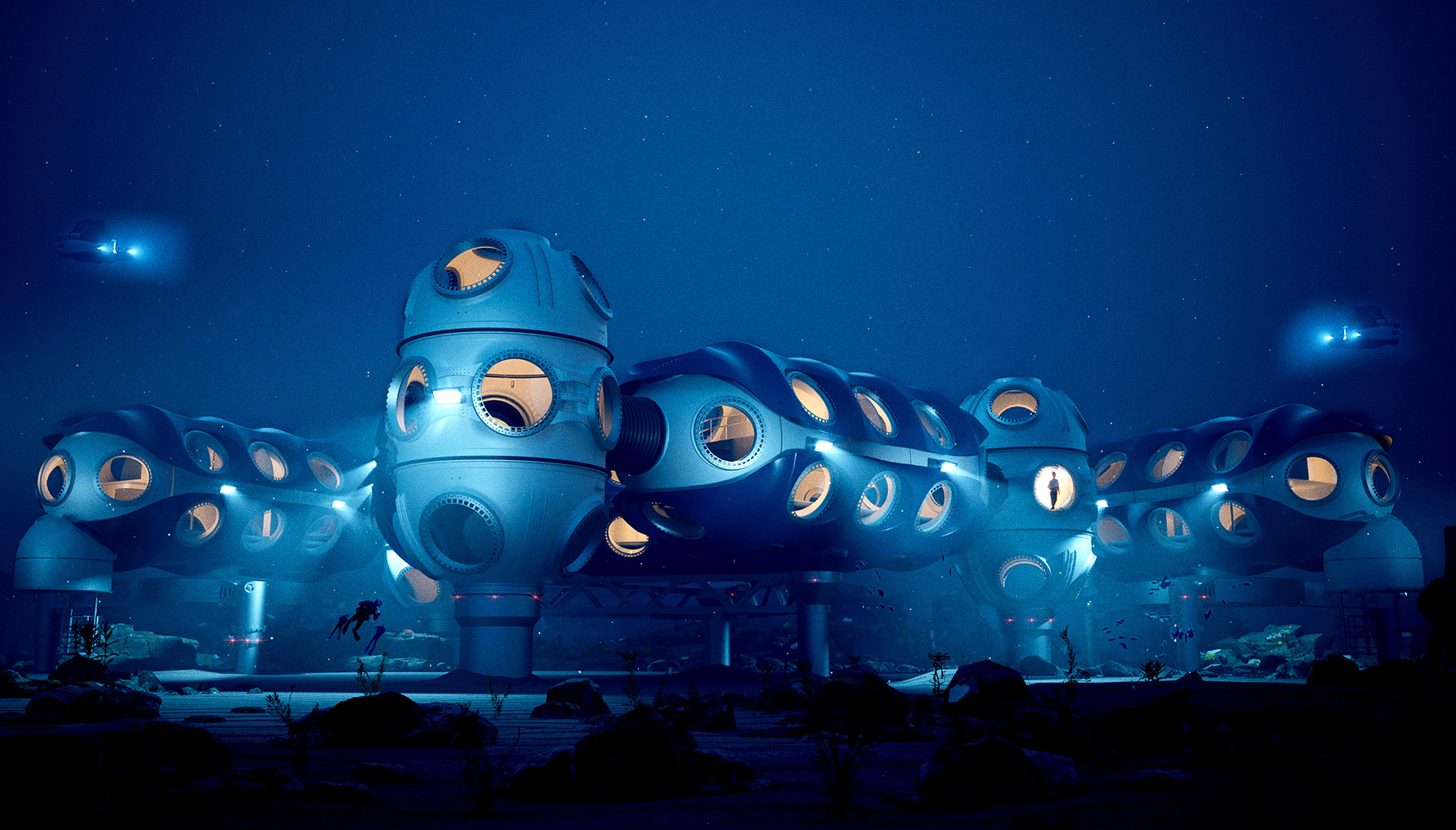

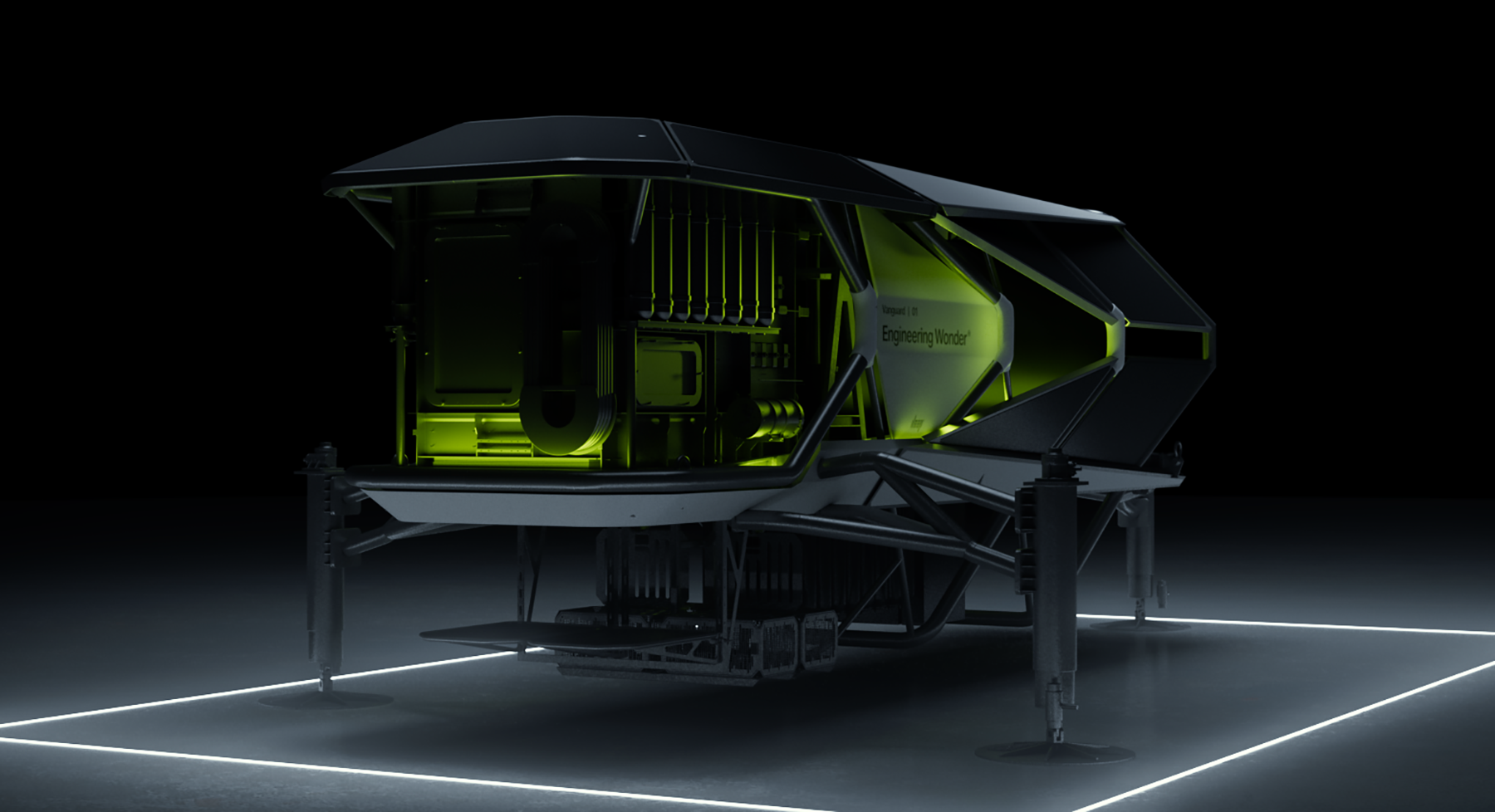

Another such project for a reconfigurable, relocatable habitat is called DEEP, an enterprise based in the United Kingdom that hopes to put a small, prototype module called Vanguard in the water this year, followed by the larger, fully modular system known as Sentinel in 2027.

Each module of the Sentinel system is designed to accommodate a six-person crew of divers, researchers and scientists, and even visitors. These modules, which can be combined to create an underwater complex, will measure slightly more than 3 meters square in cross section and vary in length.

Renderings of a Sentinel interior show relatively spacious accommodations with different levels, accessed via stairs, on which inhabitants can live and work or just watch the undersea world through panoramic acrylic viewports up to 2 meters in diameter. The complete system will feature ambient-pressure areas – matching the pressure of the surrounding water – and full-pressure areas, which are kept at levels of one atmosphere, essentially the same pressure at the surface of the water.

The ambient sections will accommodate those who will remain underwater for extended periods – known as saturated diving – while the pressure sections are designed for people making short visits to Sentinel via submarines, such as academics, members of the media, or others without diving qualifications, the DEEP website notes. Hatches will separate the pressure spheres from the ambient sections, which will feature moon pools for easy entry or exit by divers.

Extra steel where needed

Sentinel is intended for use in any ocean along the continental shelf, at depths of up to 200 meters underwater, says Norman Smith, the chief technology officer at DEEP. The movable systems will be secured to the seafloor at each site via a combination of steel frames and undersea anchors, adds Smith, a mechanical engineer whose background includes working for NASA and deep-sea equipment enterprises.

Courtesy of DEEP

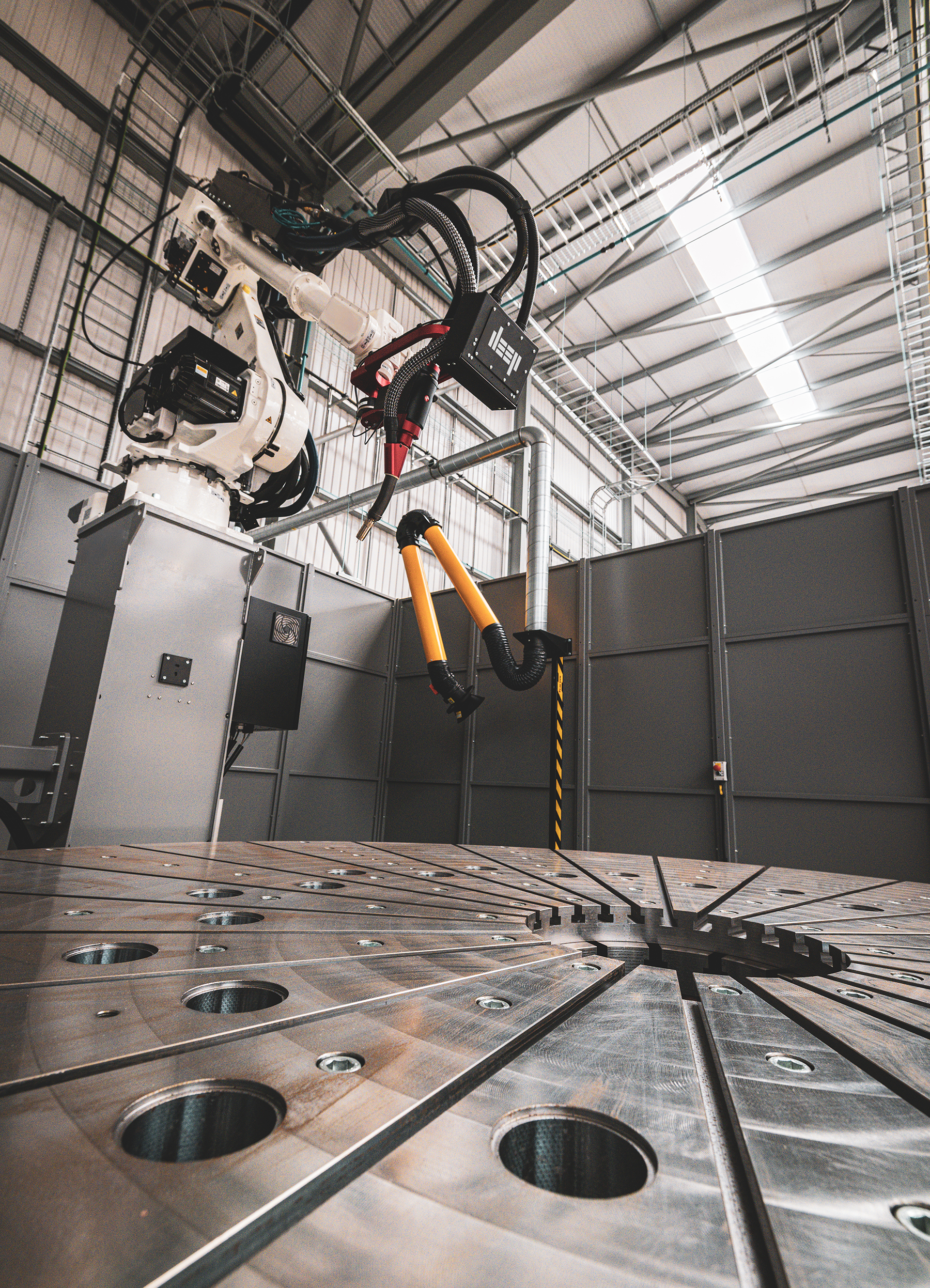

Courtesy of DEEP The different modules will be created using wire arc additive manufacturing technology that can “put more material specifically in areas that will experience the most force when underwater,” the website explains. For example, a Sentinel system at its maximum depth will require steel walls roughly 20 centimeters thick for parts of the pressure spheres while the ambient sections can be much thinner, says Smith.

Studying and submerging

To design the undersea space, DEEP’s team studied the designs of earlier habitats and created computer-aided models as well as full-scale mock-ups of Sentinel. “It amazes me the ability a mock-up has to grab your attention and communicate with engineers, nonengineers, people of all types,” Smith said. “Once you have a mock-up, you get insights and feedback you’d never get through just the (computer-aided design) world.”

Courtesy of DEEP

Courtesy of DEEP DEEP’s team also spoke with recognized experts such as Ian Koblick, the founder and chair of the Marine Resources Development Foundation, which maintains an undersea lodge in Key Largo, Florida. Some of the team also visited and studied the Aquarius Reef Base, a 40-foot-long habitat that was originally constructed for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and stationed in the U.S. Virgin Islands but has since been relocated to the Florida Keys where it is now owned by Florida International University.

DEEP’s mission involves operating its own habitats and designing facilities for others to perform undersea work and research. To further these efforts, the privately funded DEEP has established a 20-hectare campus at a protected body of water – a freshwater lake in a former quarry in the Wye Valley, near the border between England and Wales. With areas of the lake as deep as 80 meters, the site is “ideal for testing equipment, training divers, and preparing for missions,” according to the DEEP website.

In addition to the lake itself, the DEEP campus features various marine-related facilities including:

- A 17-meter-long wave and current tank for testing scale models and small full-sized elements. The tank will be able to generate waves up to 0.3 meters and currents up to 1 meter per second.

- Pressure testing facilities to simulate extreme ocean pressures of up to 30 bar, which represents a depth of roughly 300 meters underwater at varying temperatures, humidity, and diving gas mixes.

- A materials testing lab intended to ensure that materials used in the construction of the habitats do not emit toxic substances under extreme pressures.

- A 15,000-liter dive tank to test subsea technology and diving equipment, including oceanographic sensors and remotely operated vehicles.

- A stainless steel pressure vessel used to test high-current and high-voltage devices – including circuit breakers, fuses, and protective devices – under extreme subsea conditions.

“Enabling science is incredibly motivating,” added Smith, especially for engineers who often love trying to solve intractable problems such as those presented by ocean engineering.