By Robert L. Reid

As civil engineering firms grow and expand their businesses, they need to keep developing new generations of managers and senior leaders. It is challenging work, but here is a look at how several successful firms make it happen.

Tom Caldwell, P.E., M.ASCE, the senior partner and founder of Atlas Engineering Inc., in Raleigh, North Carolina, is planning to retire within the next year or so — partially retire, at least, and do consulting work. But when he leaves Atlas, he will also hand over the 12-person firm he started in 1996 to a new management team. It is a goal he has been planning and working toward for more than 20 years. Likewise, Erleen Hatfield, P.E., F.ASCE, the founder of New York City-based Hatfield Group Engineering, would like to retire in about a decade, which is why she is starting now to carefully plan how to relinquish control of her 28-person firm to new leadership as well.

This is the natural cycle of many civil engineering companies and their owners or top leaders: An engineer or team of engineers starts the business, works over the years to grow the firm and expand its operations, but ultimately must give way to new blood. When this sort of transition is planned well and implemented effectively, the firm remains strong and viable. But if the firm’s leaders have not carefully thought out what should happen after they depart, the result can undo decades of effort.

“I know of companies where all the partners wanted to retire at the same time,” says Caldwell. “And although they had built up something that had value, it was very hard to find a buyer when all the partners were leaving.”

That is why Caldwell established a long-range succession plan early on in Atlas’ history, a plan that over the past decades has been gradually transferring ownership of the firm to younger partners. From his original 100% stake in the company, Caldwell is now down to just a 20% ownership — a level that he feels means “my retirement will not disrupt the firm’s operations or finances.”

Hatfield is considering a similar approach. Currently, she and four partners own the Hatfield Group, but over the next several years she wants to formalize a plan to sell her shares to the firm’s employees because they helped build the company and made it successful, she says. And as she gets closer to retirement, she hopes to put in place a process for identifying and preparing the firm’s future leaders to take over. Who exactly those new leaders will eventually be is unknown. Instead, Hatfield and the firm’s current leadership are identifying the company’s most critical positions, what skills are needed to fill those positions, and who among the current employee base might be interested in filling those leadership roles.

Evolving ownership

At the international engineering and applied science firm Thornton Tomasetti, most senior leaders are also owners of the company throughout their careers, says Wayne Stocks, P.E., M.ASCE, Thornton Tomasetti’s president, who works out of the Washington, D.C., office. By the time they turn 65, these senior leaders are required to sell their equity back to the firm — even though many of them continue to work for years afterward. “This allows for a continuous transition of ownership to younger leaders,” Stocks explains.

As a result, the firm does not face a situation in which the largest owners all try to sell their equity at the same time. “Our model allows a continuous evolution of firm ownership,” Stocks says.

Thornton Tomasetti leaders can become owners when they reach the title of vice president, explains co-CEO Peter DiMaggio, P.E., who is based in the New York City office. “The stock committee decides who to offer shares to, and at that point you are eligible to make an investment in the firm,” DiMaggio says.

Future developments

Although a civil engineering firm’s succession plan focuses on preparing for the next generation of senior leaders, the effort is highly dependent on the continual development of managers at all levels of the company, notes Anthony Fasano, P.E., F.ASCE, the founder of the Engineering Management Institute in Ridgewood, New Jersey. Fasano’s company works with engineering clients to attract, develop, and retain the best possible engineering team.

For Fasano, succession planning “isn’t just about the CEO. It’s about managers across your firm. You need to develop them into leaders who can interact with people — because in the world we live in today and the size and complexity of our projects, you need to be able to interact with people” just as effectively as you handle the technical details of a project.

When he first entered the civil engineering field in 2000, “there wasn’t much emphasis on nontechnical skills for civil engineers,” Fasano says. But over the last 10-15 years there has been “a major shift ... in the civil engineering world about the importance of management and leadership skills for engineers,” he notes.

As a result, the most successful firms today recognize that “you have to develop your engineers into well-rounded professionals if you want them to be future leaders in your firm,” Fasano explains. “You have to think about their technical skills, their people leadership skills, their project management skills, and their business development skills — they have to be able to do all of that well.”

To help achieve such results, the firm’s leadership development efforts should be clear and flexible, Fasano says. For example, “a glaring mishap” that Fasano sees in many companies “is that there’s no clear path” for employees to advance to managerial positions. Instead, “it just kind of happens,” Fasano explains. “But if there isn’t a clear path to do something, it becomes very hard for someone to do it! Or to be aware of it or get better at it.”

However, “if you can paint a clearer picture for people (about how to advance) in your organization, they might actually get excited about becoming future leaders and seeing that pathway,” Fasano says. “Then they’ll be able to take the steps they need to take to prepare.”

Flexibility is also critical because the civil engineering industry “is changing so rapidly that the ‘right person’ today might not be the right person tomorrow,” Fasano says. That is why he recommends that companies develop “a pool of strong leaders” from across the organization.

Replacing yourself

Thornton Tomasetti sees a pool of potential leaders as an essential part of the firm’s growth plan. Existing leaders are expected to identify and develop their successors — preferably multiple people, each of whom could step into their roles, notes Stocks. In fact, Stocks jokes that he’s spent most of his career at Thornton Tomasetti “planning to work myself out of a job!”

These future leaders are created through formal and informal development programs aimed at building competencies in four key skill sets: technical knowledge, winning projects, management, and leadership, says DiMaggio. Everyone at Thornton Tomasetti operates at varying levels of expertise in these areas, DiMaggio adds, and leaders are expected to identify the areas in which employees need improvement and provide whatever support their teams need to continuously grow.

“This is critical,” DiMaggio explains, “because it creates opportunities for our next generation of leaders to take on more challenging roles. Indeed, we take this so seriously that leaders need to develop successors in order to take on new roles.”

Making managers

Over the coming years, Hatfield Group Engineering hopes to develop a formal management training program on topics such as leadership, strategic planning, risk analysis, and other managerial issues, Hatfield says. Although the firm currently conducts some general, in-house sessions on similar themes, Hatfield wants to formalize those sessions. What she envisions is a focused management training effort that might send a small group of attendees out of the office to a retreatlike setting. There, a professional trainer can coach potential leaders on a one-on-one basis, working with them on the specific areas in which they need to strengthen their skills.

These formal management training events, combined with classroom sessions on management theory and other topics, will likely be held over a long period, Hatfield says. “You don’t just become a good manager after training for six months or so,” she notes. “You need reminders, and things change ... so this type of training is helpful throughout your career.”

Comparable efforts are underway at Atlas, where Army Reserve Lt. Col. Mike Riccitiello, P.E., PMP, the firm’s president, has established a new program to train aspiring project managers. When Riccitiello joined Atlas about four years ago, the company launched a concerted effort to hire more young engineers right out of college before they even had their P.E. licenses. “But what we realized when we brought them on was that we had no formal way to train them” to become project managers, Riccitiello says.

Based on his experiences at other firms, Riccitiello combined a mentorship program involving the firm’s senior engineers with a comprehensive development program that teaches young engineers what they need to know about work at Atlas. The program begins with roughly 18 months to two years of training focused just on the technical aspects of the work — Atlas specializes in examining and repairing damaged structures — then transitions to the requirements of project management.

So far, the program has been conducted entirely in-house, but Riccitiello is considering whether to also start sending employees to formal, project-management-focused training events outside the company.

Strategic effort

For the nationwide engineering firm Dewberry, a somewhat localized succession policy — in which managers were expected to designate their own replacements — has been upgraded to be part of the firm’s five-year strategic plan, explains Erica Nelles, LEED AP, a senior principal and director of operations for Dewberry’s architectural division at the company’s Fairfax, Virginia, headquarters. The inclusion of succession planning “in the strategic plan has really elevated it and made it something that we’re now seeing more formally addressed at the organizational level,” Nelles says.

Aaron Nelson, P.E., a vice president and business unit manager in Dewberry’s Denver office, has been working on the new formalized succession planning effort with Nelles and others for several years. One concern Nelson had about the previous, localized approach to succession planning was that “some people are good at it, some people are not so good, and some people don’t believe in it.”

The old system was also highly siloed. “It might involve the people you interact with within your own group,” says Nelles, so while a manager might delegate responsibilities and leverage the resources to build up certain employees, this would happen only for those employees within that manager’s silo. But the new program represents the “next evolution” in the firm’s approach to training, development, and promoting and advancing employees, Nelles says.

Under this new effort, “we’ve become a much more collaborative organization where people are now working across offices, across disciplines,” Nelles says. “You can’t just look at the plan through the lens of just whom you interact with — you have to think about the wider organization.” So when a manager works with an employee who has incredible potential but simply doesn’t report to that manager, “as a leader, you need to advocate for that person through this framework.”

Although certain positions at Dewberry have designated successors — what Nelles calls a one-to-one strategy — in most cases the succession planning involves a process of identifying multiple candidates on the basis of their aptitudes, interests, and other factors designed to develop them as leaders. This “one-to-many” approach opens up the pool of potential leaders, says Nelles, who explains: “If you say Person X will replace Person Y, you’ve got 24 other letters in the alphabet (representing employees who) may have incredible talent but are excluded from being able to advance their career” under a one-to-one strategy.

Perhaps the greatest change in how Dewberry develops and promotes employees involves how the firm communicates career opportunities with its workforce. The new process has become much more deliberate and transparent, especially for the firm’s younger employees who are shown multiple career pathways, including newly created ones, Nelson says.

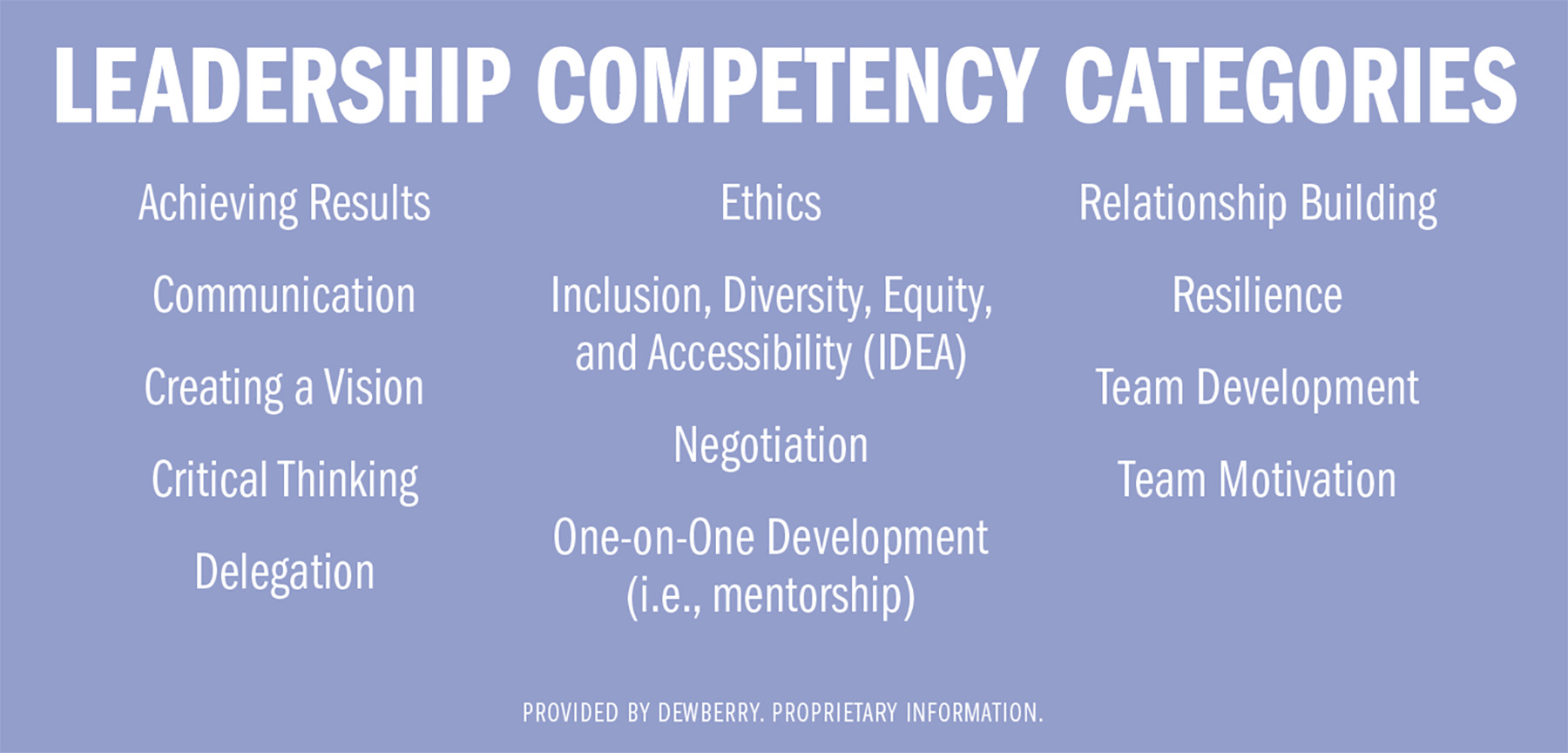

A key component of Dewberry’s approach is a leadership competency model that features 13 main categories plus an extended list of behaviors tied to those competencies. The model identifies areas in which an employee might need help to strengthen his or her abilities in certain competencies — such as someone who is very skilled technically, works well with clients, but cannot communicate well with his or her team, says Nelson. Using the model helps determine “how we work with that person ... to get the tools and resources they need to further develop that skill” in which they need support, Nelson explains.

Opting in

When civil engineering firms want to develop potential new leaders, what should they look for?

First, they need to recognize that not every engineer wants to be a manager. Some engineers prefer spending their entire careers doing technical work. For them, firms need to make it clear that there are ways to provide excellent work for clients, develop new business for their firms, and be valuable employees overall without being managers, notes Stocks.

“We won’t force someone who really just wants to be a technical person to become a manager,” adds Riccitiello. “They’re very different roles, so they have to show a propensity for management. They have to want to do it.”

At Dewberry, there are numerous opportunities that people can opt into if they’re interested in moving into management, such as monthly leadership development seminars, that they can choose to attend, notes Nelles.

To identify potential managers, Hatfield says she looks for people, even among the most junior employees, “who are self-starters, who are proactive, (and who) have a willingness to learn, to help their colleagues. These are the go-getters who want to get their projects done on time or ahead of schedule, the ones always out there helping their colleagues!”

At Thornton Tomasetti, the leadership development program includes personal skills evaluation, group sessions, in-person coaching, and detailed work plans over the course of a year, notes DiMaggio. It is a major time commitment that must be balanced with other responsibilities such as workload and personal obligations.

To help employees succeed, the goals they set during this program align with their individual areas of growth. “We’re trying to be sensitive to the fact that people are very busy, so we use their real goals!” explains Stocks. “And then these goals are fine-tuned through this process.”

Not everyone is ready to participate in the training, Stocks adds, because “we’re asking them to take a hard look at themselves and talk about their strengths and weaknesses in front of a group of colleagues. This requires a decent amount of trust and confidence. We strive to create a safe environment for our leaders. You have to decide you want to improve!”

Robert L. Reid is the senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the May/June 2024 issue of Civil Engineering as “Managing Leadership Development.”