By Adam R. Phillips, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE, and Homero Murzi Ph.D.

The best engineers seek out learning opportunities and challenge their skills throughout their careers. This study explores the concept of lifelong learning and skills development in the civil engineering workforce.

Civil engineering is rapidly evolving as research discoveries, technology, and regulations revolutionize the state of practice. In general, advances in materials and analysis fuel code and technology changes. One example of this is ASCE/SEI 7-22 Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures, released in December 2021, compared with ASCE 7-10, which was released in 2013. The latest updates have significantly changed how site class is defined, how seismic design response spectra are generated, and what is allowed for site-specific, nonlinear response history analysis.

Additionally, research surrounding mass timber structures has focused on new materials that civil engineers need to analyze and design for. These and other examples demonstrate why professional engineers need the ability to adapt to industry changes by acquiring new skills and updating existing ones — a process academics call lifelong learning.

While numerous studies have analyzed the development of lifelong learning skills among undergraduate students, only some have examined the lifelong learning skills of civil engineering practitioners with a range of professional experience. Past studies showed that the most common themes upon entering the workforce were communication, teamwork, and discipline-specific technical skills (Mazzurco et al., 2020). Since communication and teamwork have been studied by others across a range of disciplines, we set out to focus our study on the discipline-specific technical and professional skills that are learned in civil engineering practice.

The study sought to determine what skills and knowledge were required, learned, and improved upon throughout a civil engineering career and how practitioners acquired that knowledge. We also wanted to know if civil engineering professionals’ skills, knowledge, and learning modes varied across career paths or experiences. We conducted our study using a qualitative method of semistructured interviews.

Methods

We conducted 19 interviews with civil engineering practitioners at five Pacific Northwest firms. Data from the interviews were analyzed using a methodology called thematic analysis, which is a qualitative research methodology that systematically identifies and organizes patterns across interview data (Clarke et al., 2015; Froehle et al., 2022).

Participants had a range of work experience: five with less than five years of experience, seven with 5-20 years of experience, and seven with more than 20 years of experience.

Additionally, there was a range of primary job responsibilities: five entry-level engineers, three senior engineers, six project managers, one mid-career non-managing technical expert, and four vice presidents.

All participants had at least a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering, 11 had master’s degrees, and one had a doctorate. The five company profiles ranged from 200 to 10,000 or more employees.

The interviews followed a semistructured format: Interviewees answered a core set of questions, but follow-up questions differed among interviewees and provided context for participant responses.

The first two main questions encouraged participants to think about the daily tasks they performed and their career progression. These questions primed participants to think about knowledge they used on a frequent basis and skills they used for their current and past job roles.

For question 3, the interviewer inquired about knowledge or specific skills that were challenging to learn on the job. Their answers determined which skills were readily used during the engineers’ workdays, where they learned those skills, what they felt well prepared for, and what skills they learned after graduation. Question 3 and its follow-up sub-questions constituted most of the interview.

Question 4 identified participants’ perceptions of lifelong learning in professional practice in relation to mandatory professional development hours that are required in some states for P.E. licensure. A typical follow-up question was whether participants thought PDHs should be required.

The final two questions sought to determine whether participants identified additional skills or knowledge that they would need in the future to meet their professional goals. We wanted to know if they had made plans for that learning or felt confident in their abilities to acquire those skills.

A thorough explanation of the study methods and a full description of the study findings can be found in “Understanding lifelong learning and skills development: Lessons learned from practicing civil engineers” (Froehle).

Summary of Findings

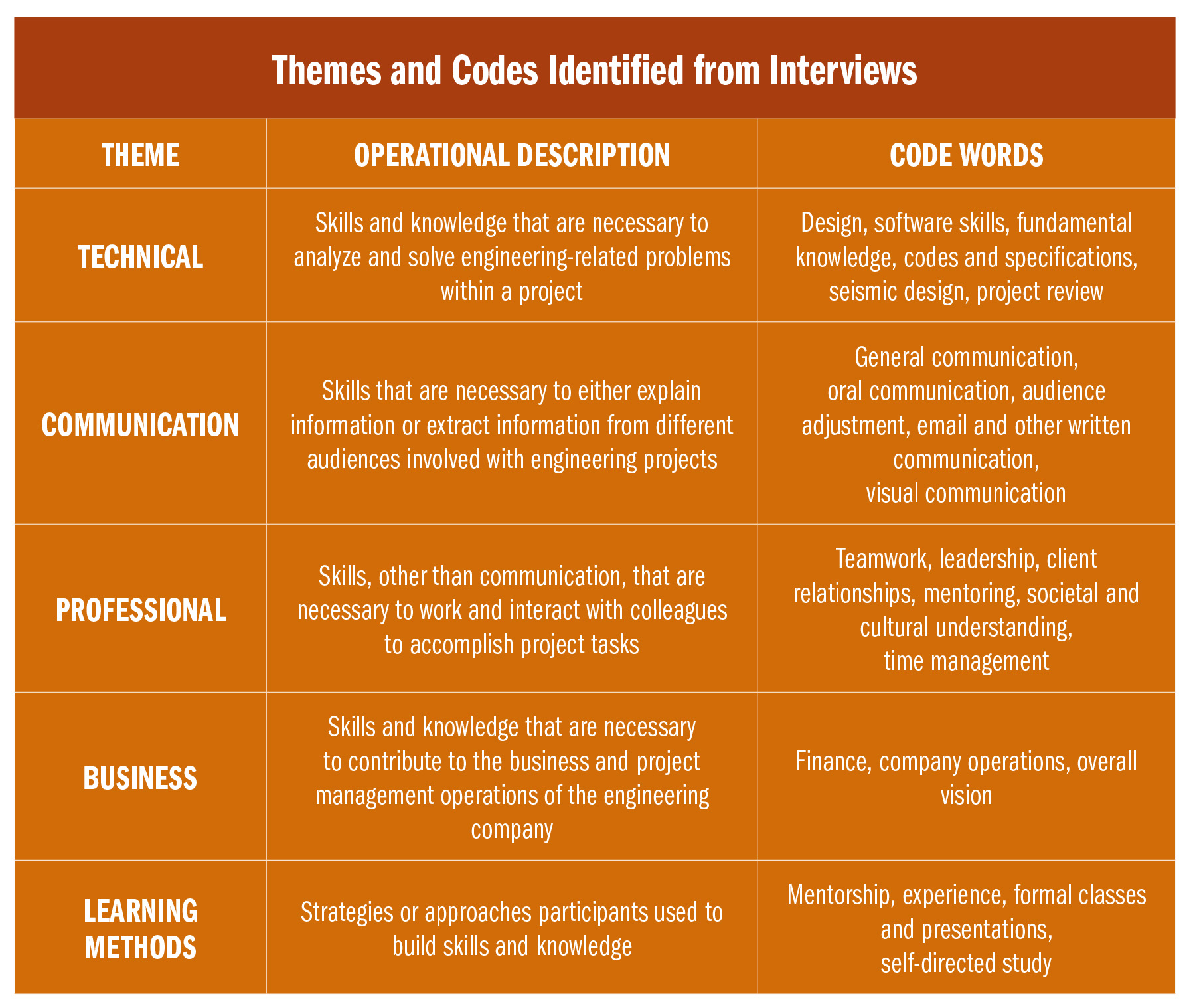

One finding in this study was the complex array of knowledge and skills required for successful civil engineering careers. In school, the focus of engineer training is on a relatively small set of skills mostly focused on math, engineering analysis, and engineering design. However, in practice, the skills that were described as required for a civil engineering career were much broader than that. We classified this knowledge and these skills into larger generalized themes, which we described by a set of detailed code words. This provided a taxonomy of the civil-engineering-specific knowledge and skills needed for lifelong learning, which are presented in the table below.

The most civil-engineering-specific theme was technical skills. All participants discussed the necessity of technical skills, especially entry-level engineers performing the majority of day-to-day design and analysis tasks. The most frequently discussed technical skills were general design (17/19) and software skills (11/19). Interestingly, general software skills in programs such as email and word processors were discussed as much if not slightly more than software skills in civil-engineering-specific programs, such as SAP2000 or Civil3D. Senior engineers stressed fundamental concepts of design, while entry-level and mid-career engineers stated the need to know how to use software, codes, and design standards.

While senior engineers (including vice presidents and presidents) did not often complete design tasks in their daily work, interview responses showed that overall, they were some of the most highly respected, technically knowledgeable, competent individuals in their firms. This was an interesting finding because it suggests that on the way up the leadership ladder at professional firms, even the most business-focused roles require a solid understanding of technical materials.

While other studies have identified communication skills as being important in professional practice, some of the civil-engineering-specific detail provided that related to communication was the need for audience adjustment. Project managers and vice presidents mentioned this as a required skill for civil engineers. Because of their more outward-facing roles in their companies, they often explain to potential clients or collaborators, such as architects, the role of their engineering firm in broad terms, focusing on big-picture goals and outcomes versus diving into analyses or design components.

Additionally, audience-adjusted communication was mentioned as crucial for explaining to clients and building owners the purpose of their companies’ services and what they deliver. One vice president stated that the ability to communicate effectively is the primary skill needed for career success.

Another common discussion topic was email as the dominant form of written communication in comparison to memos or reports.

Professional skills (skills other than communication) were discussed mostly by vice presidents, project managers, and senior engineers, especially those with leadership and management roles. However, one exception was client relationships, which was mentioned by 15 of 19 participants. In addition, 15 participants recognized the need to develop interpersonal and networking skills further after graduation. One vice president described civil engineering as a service industry, meaning client relationships are paramount to a firm’s overall stability.

Practitioners in the study employed a wide variety of learning methods. All practitioners discussed lifelong learning as an essential component of professional practice. Mentorship was one of the most discussed methods of learning, mentioned by 17 of the 19 participants. Some participants referenced their companies’ formal mentorship programs, while others reported relying solely on informal mentors.

Being able to ask mentors well-thought-out and specific questions was one of the most emphasized skills by participants. Sixteen of 19 participants also discussed learning new skills while working on projects. They emphasized learning on the job through experience in industry as a good way to pick up new skills.

All 19 participants discussed using formal short courses or presentations as a preferred method of learning. In particular, short presentations, often termed lunch-and-learns, were mentioned by many participants as an accessible resource for learning new skills or knowledge.

One of the main findings of the study was identifying the importance of being able to learn through individual interactions and on-the-job design experience. This is important because while some learning modes, such as formal short courses or presentations, may parallel the school environment, most of the learning at work depends heavily on interpersonal relationships, asking questions, and developing effective mentorship relationships with experienced, superior civil engineers. This transition from school to work means entry-level engineers need to be prepared to move from structured, classroom-based learning to informal, networking learning environments (Paretti et al., 2020).

Implications

The skills and knowledge acquired during a civil engineering career are widely varied. There is a heavy focus on technical knowledge and skills, including fundamental concepts, design skills, and knowledge of codes and software, as it should be in a highly technical field like civil engineering. There are also location-specific skills, such as seismic design, that suggest new engineers will have to build significant regional-based technical skills relative to their firm’s project profile. Employers may want to consider learning opportunities, such as lunch-and-learns, that address their firms’ specific technical needs.

Additionally, most participants mentioned learning through mentors and peer interactions, so firms may want to consider establishing mentorship programs or technical “advisers” who specialize in teaching newer engineers technical skills.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, communication remains a critical skill for engineering practice. Most notably, this study echoed findings from outside engineering practice that email is the most frequent form of written communication, internally and externally, in business environments. Therefore, educators and professional mentors should consider incorporating more training on the efficient use of this communication mode.

Our participants made clear that learning is lifelong in professional practice and encompasses a wide range of technical and professional topics. Those topics shift as a career progresses, from being more technically focused to being more leadership and business focused. As undergraduate and graduate civil engineering programs and employers seek to effectively integrate new engineers into the workforce, providing support for lifelong learning and skills development will be essential.

References

Clarke, V., Braun, V., & Hayfield, N. (2015). Thematic analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 222–248). Sage Publications.

Froehle, K., Dickman, L., Phillips, A. R., Murzi, H., & Paretti, M. (2022). Understanding lifelong learning and skills development: Lessons learned from practicing civil engineers. Journal of Civil Engineering Education, 148(4): 04022007. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.2643-9115.0000068

Mazzurco, A., Crossin, E., Chandrasekaran, S., Daniel, S., & Sadewo, G. R. P. (2020). Empirical research studies of practicing engineers: A mapping review of journal articles 2000–2018. European Journal of Engineering Education, pp. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2020.1818693

Paretti, M., Kotys-Schwartz, D., Ford, J. Howe, S., & Ott, R. (2020). Leveraging the capstone design experience to build self-directed learning. International Journal of Engineering Education, 36(2), pp. 1-11.

This article is adapted from the 2022 paper “Understanding lifelong learning and skills development: Lessons learned from practicing civil engineers” by Kamryn Froehle, Logan Dickman, Adam R. Phillips, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE, Homero Murzi, Ph.D., and Marie Paretti, Ph.D., in the Journal of Civil Engineering Education.

Adam R. Phillips, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE, and Homero Murzi, Ph.D., are associate professors in the department of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech.

This article first appeared in the May/June 2024 issue of Civil Engineering as “Lifelong Learning for the Civil Engineer.”