By Jonathan E. Jones, P.E., P.H., BC.WRE, F.ASCE, Natalie M. Collar, Ph.D., CFM, HIT, Brett Stewart, Esq., Maanav Jhatakia, and Ava Spangler

Because climate conditions are becoming more variable, water infrastructure engineers face multiple challenges regarding long-term weather projections. The authors recommend that designs for future water resources management systems account for such climate dynamism.

To gauge the extent to which our engineering and scientific colleagues in the United States are addressing the challenges of climate dynamism in their water-related projects, the authors conducted a literature review and a survey asking the following questions:

- Are you accounting for increasingly variable climate patterns and more extreme weather events in your water-related engineering or scientific practice?

- If so, can you provide examples of design modifications or updates you or your staff have made?

- Do you believe the standard of practice for water engineers now requires accounting for current or anticipated future changes in climate and weather?

Changing methods

Thirty-seven people — representing private engineering firms, academia, and municipalities, among others — responded to the survey and indicated that they are indeed modifying their historical planning and design practices to account for more extreme climate conditions.

For example, hydrologic models help engineers quantify how much rainfall will transform into runoff at a particular location. Because most of these models include variables such as precipitation and temperature, the modeling phase of an engineering project is a good point at which to address changing climate conditions. To that end, some survey respondents couple their hydrologic models with climate models to capture changes in meteorologic variables over time.

When these models are used to support infrastructure development, the primary motivation can be to protect the project from larger or more frequent flood events. Many respondents recommended adjusting precipitation rates and volumes or directly adjusting design flood events to account for the range of potential climate conditions. Other specific recommendations included increasing precipitation intensity in design storms, widening confidence limits, and bumping up the magnitude of design floods. The use of analytical methods for quantifying uncertainty of key variables was also suggested, as was the importance of updating design guidelines to require precipitation trend analysis and mandating that design storms and floods be reevaluated regularly.

Design rainfall and floods were also discussed in the literature reviewed for this paper, with varying recommendations, such as increasing the 10-year design storm by 50% by 2100. Another suggestion was to reevaluate design rainfalls annually and introduce uncertainty parameters for the design criteria most vulnerable to change under future climate scenarios. This aligned with one of our more common survey responses, which was to update water infrastructure design guidelines with the most recent precipitation data when the data become available.

Other recommendations included developing flood estimates that reflect “high” and “low” runoff scenarios and using partial duration instead of annual peak series when calculating rainfall recurrence intervals.

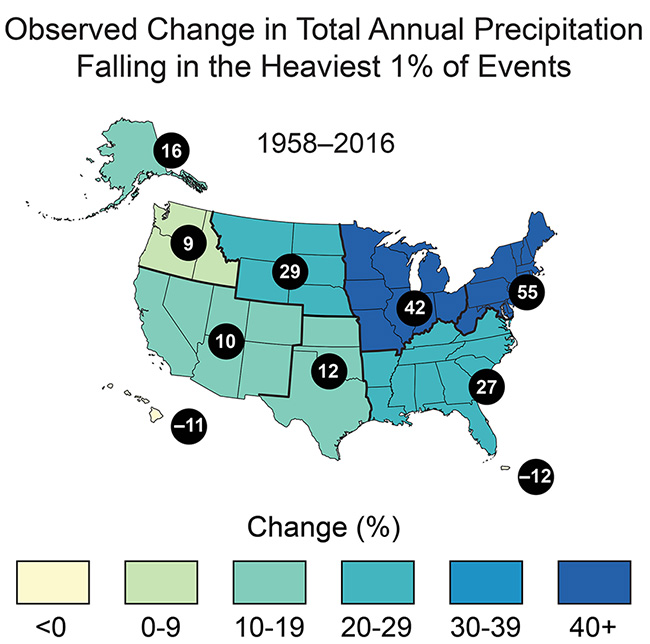

Regardless of how practitioners choose to address hydrologic variables in modeling, the authors urge them to analyze data specific to their project area and not to generalize. Figure 1, created by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, provides a compelling example of regional differences in the total annual precipitation amounts produced by the heaviest 1% of storms.

Confronting vulnerabilities

Ensuring adequate water supplies and managing demand, particularly in urban areas with dense populations, were key concerns for the respondents. One of the top concerns for water providers is to generate water supply and demand projections that will identify future potential demand gaps and shape protocols that will help reduce those gaps, including through water conservation and drought preparedness.

Analyzing the vulnerability of urban water supply sources to changing hydrologic conditions will also be necessary for long-term water management. In this vein, several survey responses mentioned how forested source water areas and collection systems in the arid southwestern United States can be degraded following wildfire disturbance.

Improving climate and weather forecasting methods, such as by increasing their accuracy and lead times, will help water managers foresee when and where severe storm activity may develop — and thus help them take cost-saving preventative measures.

Design storms should be updated periodically, especially in regions where climate conditions are changing rapidly. For coastal regions, the risks from flooding and sea-level rise should be analyzed to understand how water infrastructure can be fortified, from both structural and water quality perspectives. Survey respondents also recommended expanding the capacity of water and wastewater treatment facilities to meet future demands in areas with growing populations.

Implementing innovations

Many innovative water supply strategies are already in use in the western U.S. to address extreme hydrologic fluctuations. For example, farmers and ranchers in Colorado with senior irrigation water rights have established flexible agreements with municipal water suppliers to provide their irrigation water for municipal purposes in dry periods in exchange for financial compensation. Treated municipal and industrial effluent is often leased by the discharger to other water users, and highly treated effluent is increasingly being used for aquifer recharge for indirect potable reuse as well as other beneficial uses in Arizona, Florida, Texas, California, and other states.

Regulators in California have recognized that flow storage restrictions during wet periods should be relaxed to ensure supplies for drier periods. Water conservation strategies are becoming more restrictive yet effective. There is increasing discussion — among project proponents, regulators, and the public — of interstate, long-distance pipelines to convey flows from water-rich to arid regions, such as from Wyoming to Colorado. Local and state elected officials are making difficult decisions on proposed developments and other land uses based on water supply limitations in Wyoming and Colorado, among other states.

Controlling flooding

Drainage and flood control recommendations from survey respondents and in the literature generally revolved around strengthening current infrastructure, updating design standards based on more extreme climate scenarios, and employing nature-based solutions and practices due to their effectiveness and resilience to extreme weather.

Enlarging culverts and other stormwater and flood control infrastructure to accommodate projected flow rises and increasing vertical freeboard on flood-prevention structures, were two such responses. Similar actions are recommended for structures inside and out of mapped floodplains. These measures include building to or above the 500-year flood elevation and lateral extent (versus the 100-year regulatory floodplain) because the 500-year event captures the risk of more severe floods.

Respondents recognize that some floodplain maps prepared cooperatively with the Federal Emergency Management Agency under the National Flood Insurance Program under-estimate the magnitude and extent of inundation during 100-year flood events. They also acknowledge that, in some areas, the magnitude, frequency, and duration of design rainfall amounts are too low and must be increased.

Similarly, the survey responses, published literature, and the authors’ professional experience indicate that drainage and flood control design criteria have become more conservative in many jurisdictions. This is demonstrated by freeboard requirements for channels, storage facilities, and levees; finished-floor elevations; design storms and flows; setbacks and buffer zones; and floodplain development restrictions. For example in Houston, the lowest habitable floor in new developments was increased to 2 ft above the 500-year flood elevation following Hurricane Harvey.

Respondents also indicated that recommendations and requirements regarding freeboard at levees should be increased. Dam design criteria are also expected to be more conservative where merited, such as in wildfire-prone watersheds, potentially resulting in larger and more expensive structures.

Under some circumstances, raising levee heights can be a cost- effective approach for mitigating flood risk. Some survey respondents recommended designing levees to historical maximum flood levels and using flood damage reduction analysis models to analyze uncertainties of levee height and strength. Of course, the hazards associated with levees must be accounted for as well.

Survey respondents frequently discussed the need to update design standards for flood control infrastructure, including the use of a linear relationship between return periods and time as a simplified criteria point for climate variation-centered design. They also cited the impact of identified changes in relative sea level on the flood protection capabilities of, and loading stresses applied to, infrastructure.

As with other categories, adaptive planning and policy strategies are considered crucial, including the use of nature-based solutions and policies to restore wetlands, riparian areas, and other infrastructure that can naturally help to regulate drainage and flooding. Adaptive assessments are also recommended to help design engineers evaluate infrastructure performance during extreme weather and identify sources of uncertainty.

Reducing hazards

Survey respondents observed that water resource practitioners should account for the impacts of changing climate conditions on natural hazard frequency and severity, including from atmospheric processes such as pluvial and riverine flooding, landslides and debris flow, sea-level rise, and storm surge.

Specific design responses to protect existing water infrastructure from larger floods include adding structural protection measures to coastal infrastructure to combat sea-level rise. In addition to using stress tests to identify and remedy weaknesses in infrastructure systems, this approach can also include adaptive management plans for buildings to accommodate operations based on present conditions.

Respondents suggested elevating critical buildings in flood-prone areas to accommodate historical maximum flood levels and updating floodplain and groundwater elevation maps to protect such assets. Moreover, recent meteorologic and hydrologic data and distributions that capture extremes can be used to update design storms.

Turning to nature

Survey respondents highlighted a need for river or streambank protection and the greater use of nature-based solutions for bank protection. These measures — which rely on natural dunes, oyster reefs, and bio-engineered bank protection, among other approaches — have become more prevalent for addressing stormwater management, ecosystem protection, the mitigation of urban heat-island effects on local water, and coastal protection. One respondent, a geomorphologist, recommended using landscape information and data reflecting historical climate extremes to help design water-related infrastructure, such as structural hazard mitigation projects.

Other respondents recommended more traditional “hard” engineering measures such as modifying hydraulic barrier walls, while our literature review indicated that anchorage bars and concrete shear tabs can help mitigate losses from scour, coastal erosion, and wind damage. New materials, such as ultra high-performance concrete, and the use of sustainable construction techniques could also boost the resilience of the built environment while simultaneously reducing a project’s environmental footprint.

Another issue cited by respondents involved the need for more accurate post-fire hydrogeomorphic hazard prediction models, especially in the fire-prone western U.S. This topic is driven by recent increases in wildfire-related damage resulting from more severe fire activity and more opportunities for losses as human development expands into flammable landscapes, such as the catastrophic fires in the Los Angeles metropolitan area in January 2025. Survey respondents made several recommendations, including:

- Pre-fire hazard planning. For example, developing forest management programs that reduce the likelihood of severe fire behavior, analyzing asset susceptibility to post-fire hazards, and designing wide floodplain corridors in and downstream of fire-prone watersheds.

- Post-fire emergency mitigation, such as removing or hardening culverts located above high-value assets and resources, and rapid application of hillslope erosion mitigation measures such as hydromulch.

- Watershed rehabilitation programs, such as hillslope seeding, to increase the pace of hydrologic recovery.

Maintaining water quality

Survey responses indicated that engineers who work with water supply and wastewater treatment systems increasingly agree that more extreme weather must be accounted for in the design process. For example, infrastructure needs to be capable of withstanding higher flows and concentrations of some pollutants following high-intensity rainfall in disturbed source water areas; additional wastewater treatment capability must be provided where baseflows are projected to decrease; and water intake structures may need to be modified.

Changes in water quality policy and regulation may be required to accommodate water quality changes. For example, increased pollutant concentrations caused by extreme weather can make it more difficult to attain discharge permit limits from the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. In response, more low-impact development and green infrastructure measures can help urban stormwater systems reduce runoff rates and volumes. Greater investment in methods to address separate and combined sewer overflows can also help reduce the magnitude and frequency of overflow events.

Overcoming obstacles

While survey respondents identified the need to incorporate climate variability and uncertainty into the design and management of water projects, they also recognized several key obstacles to accomplishing that goal:

- County and municipal governments responsible for implementing capital improvements on water resources infrastructure are already struggling financially to keep up with current permit requirements that do not explicitly account for climate variability.

- Non-stationarity and non-uniform distributions make it challenging to account for potential climate conditions.

- It is difficult to calibrate “future conditions” model scenarios.

- Published data often have a multiyear lag time.

- There can be a disconnect between engineering and climate resilience staff at water utilities.

- Standard-of-care concerns can deter the implementation of novel practices because codes and standards are generally static and backward-looking, and they evolve unevenly.

- The public often opposes rising costs and disruptions to their daily lives posed by climate-conservative efforts, and they remain skeptical of projected benefits.

Ignoring climate variability and uncertainty is ill-advised and may result in projects that do not appropriately protect public health, safety, and welfare, which is the paramount responsibility of all licensed professional engineers.

Water resources engineers and scientists should also consider the potential legal and professional liability implications if they do not account for climate variability and uncertainty in their projects. A 2021 study presented in the Nature Climate Change article “Filling the evidentiary gap in climate litigation” evaluates the difficulties of litigating climate-related claims. The authors posit that climate litigation — in which the plaintiffs seek financial remedy from greenhouse gas emitters for alleged climate change-related losses — is becoming more common.

Although few of these claims have been successful so far, that could change as legal teams and experts grow more skilled at compiling and presenting robust climate science, according to the article.

In this same vein, the insurance industry routinely defends engineers against claims that a more robust design would have better accounted for the impact of a severe weather event. It is an argument that may gain traction with juries whose members have little to no design or construction experience but who are open to expansive views of climate science.

That possibility coincides with a trend in stronger standard-of-care provisions and contractual indemnities in agreements with project owners. These provisions and agreements create greater risk for engineers by contractually obligating them to guarantee higher levels of project performance and to assume higher degrees of liability for unfavorable outcomes. For public projects, engineering consultants may face additional legal exposure, as public agencies enjoy a level of governmental immunity not available to private entities.

At the same time, the cost to engineers of procuring professional liability insurance has gone up, and deductibles and self-insured retentions are also higher. Such costs are not easily passed on to public agencies with limited budgets. Moreover, in locations where natural catastrophe losses are on the upswing, property insurance carriers may charge higher premiums for lower coverage, or they may exit certain geographical markets altogether. With less property insurance available to cover damage from severe weather events, engineers may bear more of the cost when their projects fail.

So, what can be done about all this? We see the solution as a multifaceted approach, where design professionals continue educating their clients about the increased risks posed by climate variability and uncertainty and apply as much location-specific data as feasible (rather than generalizing).

Design professionals should also stress the benefit of considering project life-cycle costs over short-term funding, acknowledge the potential unintended consequences of any actions or designs that do not directly address climate variability and uncertainty on themselves and other parties, and work to establish a more equitable contracting environment that better allocates risk.

Additionally, for public- and private-sector project owners, program requirements that include the assessment of climate variability and uncertainty are encouraged and will help provide needed direction and certainty for project designs that exceed the traditional standard of care. The path toward designing for a more resilient future lies in fostering robust communication and collaboration among all project stakeholders.

Jonathan E. Jones, P.E., P.H., BC.WRE, F.ASCE, is CEO and Natalie M. Collar, Ph.D., CFM, HIT, is senior hydrologist at Wright Water Engineers. Maanav Jhatakia is an analyst at Adamantine Energy. Ava Spangler is a graduate student at Pennsylvania State University. Brett Stewart, ESQ., is manager of loss prevention and education at AXA XL.

References

Kunkel, K. E., Ballinger, A., Biard, J. C., & Sun, L. (2017). Observed and projected change in heavy precipitation. Our Changing Climate. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: The Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II.

https://data.globalchange.gov/report/nca4/chapter/our-changing-climate/figure/heavy-precip

Stuart-Smith, R. F., Otto, F. E. L., Saad, A. I., Lisi, G., Minnerop, P., Lauta, K. C., Van Zwieten, K., & Wetzer, T. (2021). Filling the evidentiary gap in climate litigation. Nature Climate Change, 11(8), 651-655. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01086-7

*For a complete list, please contact Natalie Collar, Ph.D., CFM, HIT: [email protected]

This article first appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “Dealing with Water and a Dynamic Climate.”