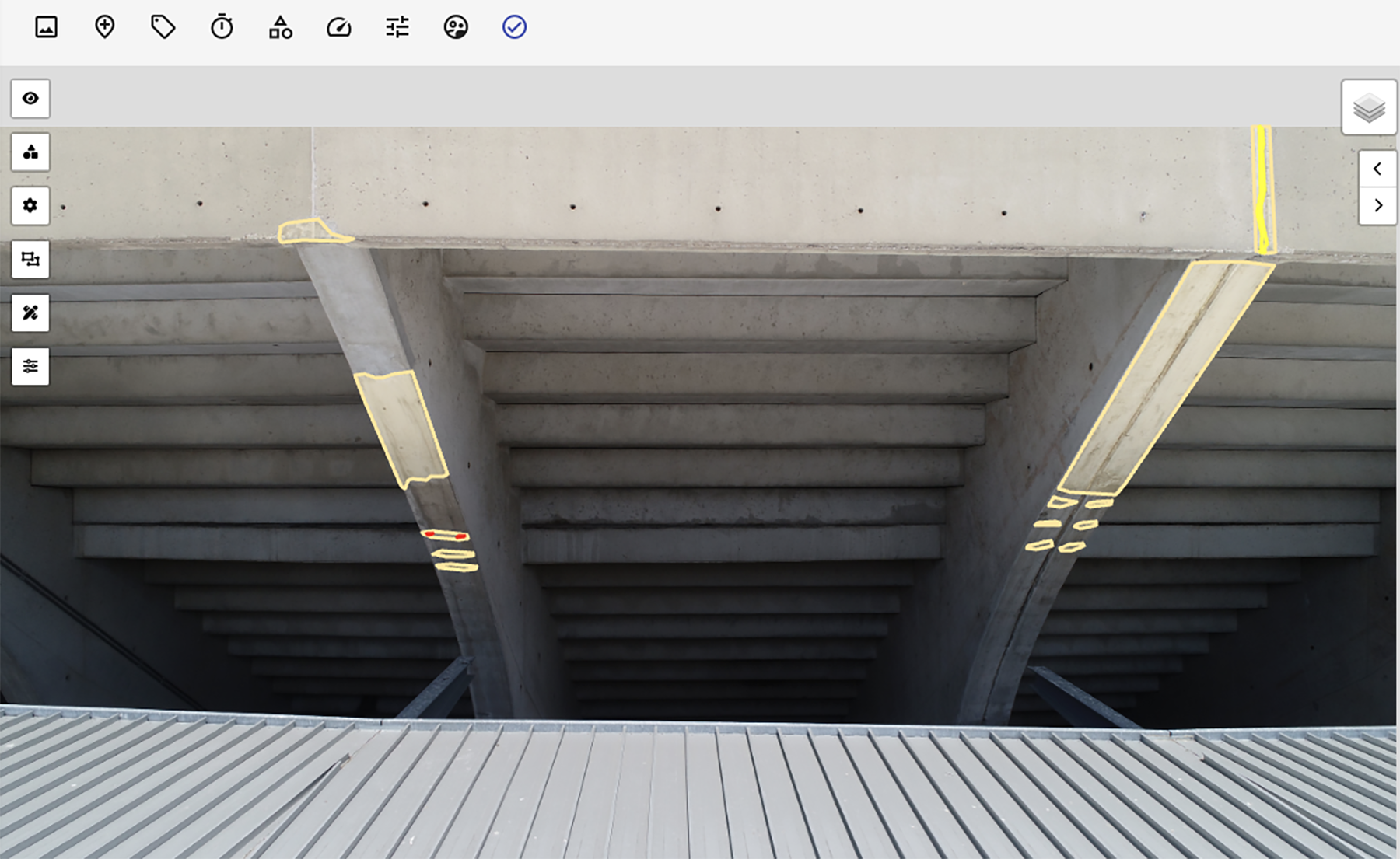

Thornton Tomasetti’s T2D2 app uses artificial intelligence to quickly detect defects such as cracks or exposed rebar in photos and videos. (Image courtesy of Thornton Tomasetti)

Successful adopters of artificial intelligence need to recognize a shift in how we view computer results, according to experts in the architecture, engineering, and construction industries. Users must expect fallible outputs from AI systems instead of taking at face value the calculations of traditional software. In return, the speed improvements offered by AI will render a competitive advantage that cannot be ignored.

Globally, 84% of AEC companies plan to increase their AI investment over the next five years, with 48% of firms already using AI in design and 42% in planning, according to a report released by Bluebeam in October.

Robert Otani, P.E., LEED AP BD+C, M.ASCE, chief technology officer at Thornton Tomasetti, a global engineering consulting firm, says that his company uses an AI app that can produce in seconds building designs that would take a team of engineers weeks to compile. The speed not only allows for more iterations in a project’s early design phases but also provides more information at the right time.

“Many times, in a traditional project, if the answer comes back too late, you're not adding value,” Otani said. “Also, you're not getting the information in time for all the appropriate decisions to be made.”

Further reading:

- What do civil engineers need to know about artificial intelligence?

- The AI revolution is here

- Artificial intelligence detects fires early, protecting people and infrastructure

AI technology is arriving after several decades of declining productivity in the AEC industry, said Stephanie Slocum, P.E., M.ASCE, founder and CEO of Engineers Rising LLC.

Historically, architects served as sort of “master builders” familiar with all aspects of projects, she said. “As things have gone on, we’ve gone more niche, niche, niche with specialties. So, instead of having generalists in our field, we now have moved to this place where we have a lot of specialists who are in their very narrow degree of focus, and that is the thing they know. Our business models are often set up to prioritize that (and) encourage folks to stay in their lane.”

A constant risk of litigation has also meant “everyone is very interested in documenting everything,” continued Slocum. “Mesh those together, you have created this environment where the productivity of an individual firm (or) organization is prioritized over the productivity of a full project.”

Slocum believes that using generative AI to facilitate communication between silos or with clients is one area where the technology is ready to make a big impact.

“This productivity drain is so ripe for disruption,” she said.

New jobs for an old idea

Machine learning – the ability of computers to produce results without explicit instructions for those results – traces its roots to the mid-20th century.

In 1943, neurophysiologist Warren McCulloch and mathematician Walter Pitts wrote a paper describing how models of human neurons, such as those using electrical circuits, could alter their outputs based on their inputs and the states of their internal nodes. While the excitement of a neural network’s computational powers has waxed and waned over the ensuing decades, machine learning has since found applications in areas ranging from spam detection to medical diagnosis to social media curation.

On top of steady gains in computer-processing speed, recent large language models, which allow conversational interfaces such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, or Meta’s Llama, have made machine learning more accessible than ever.

“It's not a technologist sitting in a room playing with Python and figuring something out,” Otani said. “It's widespread across the world.”

The need for checks and sandboxes

That accessibility has led to ethical concerns specific to the AEC industry.

Slocum likened an AI program to “a very intelligent assistant that is not trained on any subject matter knowledge. So, I have no business asking the AI to do anything that I cannot personally vet that I do not have the subject matter expertise.”

When engineers fail to disclose their use of AI, the issues extend beyond passing off others’ work as their own. Such slights also sidestep validation steps necessary when accepting the work of someone – or something – without a professional engineering license.

Otani added, “Our industry is based around life-safety issues, so the stakes are significantly higher than, say, Instagram, Facebook,” or other companies focused primarily on advertising.

Compounding risks, the data on which AIs are trained remain a black box to users. Slocum referred to a 2019 preprint by Georgia Institute of Technology researchers that showed how self-driving cars performed better at detecting pedestrians with lighter skin tones than darker ones, likely as a result of the datasets used for training.

And AI programs’ current terms of use also present privacy risks to client data if not handled correctly.

“For instance, if you upload a document into ChatGPT, that document is now essentially given to OpenAI,” Otani said. “And that will be likely to show up in the next training model that comes out.”

Thornton Tomasetti has therefore established policies that require sandboxed systems – those confined to the firm’s internal network – when feeding in certain client data. The policies also define clear steps for verifying anything an AI produces. Otani says the value of AI currently lies in the earlier design phases, where rapid iteration can help establish a starting point from which engineers can continue.

Engineering, planning, and design consultant Kimley-Horn has taken a fast-follower approach, monitoring AI trends and advancements and comparing the potential benefits and risks against the firm’s operational goals, according to J. Nick Otto, the company’s chief information officer.

“In the AEC industry, quality control and assurance are crucial, especially when using generative AI in work production,” Otto said. “The design of critical infrastructure demands rigorous standards, and as AI influences design decisions and becomes a tool in the process, we must fully understand and carefully manage its influence on design decisions.”

The firm has established a dedicated AI support team and a central knowledge hub where staff can learn and share guidance on the use of AI.

“Kimley-Horn established guidelines to ensure safe, responsible, and productive AI implementation, including recommended tools, best practices, training, and tailored education,” Otto said. “To encourage safe innovation and exploration, staff are provided with AI sandboxes – controlled environments where they can explore emerging AI tools without risk to client data.”

About 28% of respondents in the Bluebeam report said they allocated more than 25% of their information technology budget to AI.

Looking ahead

Otto says that training transparency will be crucial to future AI use in the industry.

“Understanding datasets, decision-making processes, and integrity measures helps in selecting the best solutions,” he said. “Trustworthy AI technology providers with AEC industry expertise are essential and will help foster confidence in the role AI will play in the industry in the future.”

Following the technology’s adoption period, Otani believes that the role of human engineers will shift more toward “solving really hard problems” as computers take on more and more of the mundane tasks. He compared the current situation to the adoption of personal computers in the 1990s.

Engineers entering the field, although not required to be data scientists, should at least have a basic understanding of how machine learning models work, he continued. “Then you can find both the opportunities and the risks associated with utilizing the technology.”