Edited by Robert L. Reid

Question: When is a beach not a beach?

Answer: When, like the Pioneer Square Habitat Beach project in Seattle, the beach is designed more as a waterfront marine life habitat than as a spot for sandcastles and sunbathers. In fact, the site has no sand for visitors to play in or lie on. But don’t worry. Pioneer Square Habitat Beach is definitely a place for the public. It’s just that a visit there won’t be your average day at the ... well, you know!

Civil Engineering discussed the Habitat Beach project with Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront & Civic Projects, which provided the written answers detailed below. The answers have been edited for length and clarity.

CE: Please discuss an overview of the project, including how it fits in with other efforts in the works.

OW&CP: The Pioneer Square Habitat Beach is part of a larger redevelopment of the Seattle waterfront that began with the closure and demolition of the Alaskan Way Viaduct in 2019. The goal was to reconnect the city to its waterfront, which will be accomplished through 20 acres of new parks and public spaces. These include a park promenade, a protected bike lane, and gathering spaces along Elliott Bay. In addition, Pier 62 and Pier 58 will feature community events and active recreation. A new elevated park will connect the historic Pike Place Market with the waterfront, providing expansive views of Elliott Bay, and other new amenities are also planned.

When Seattle’s existing waterfront was developed in the early 20th century, Elliott Bay lost many of its natural habitat features for fish, including sloping beaches, crevices, and vegetated hiding places for salmon. So the goals of the project were to increase opportunities for the public to be close to the water and to support a robust marine habitat by restoring the function of a natural shoreline and improving ecosystem productivity.

Further reading:

- NASA beach project requires the right stuff – even for Florida sand

- $40 million aquatic habitat restoration in Seattle provides a home for salmon

- Fine-tuning a model to better predict erosion of steep beaches

CE: How is the Habitat Beach project connected to the replacement of the Elliott Bay Seawall?

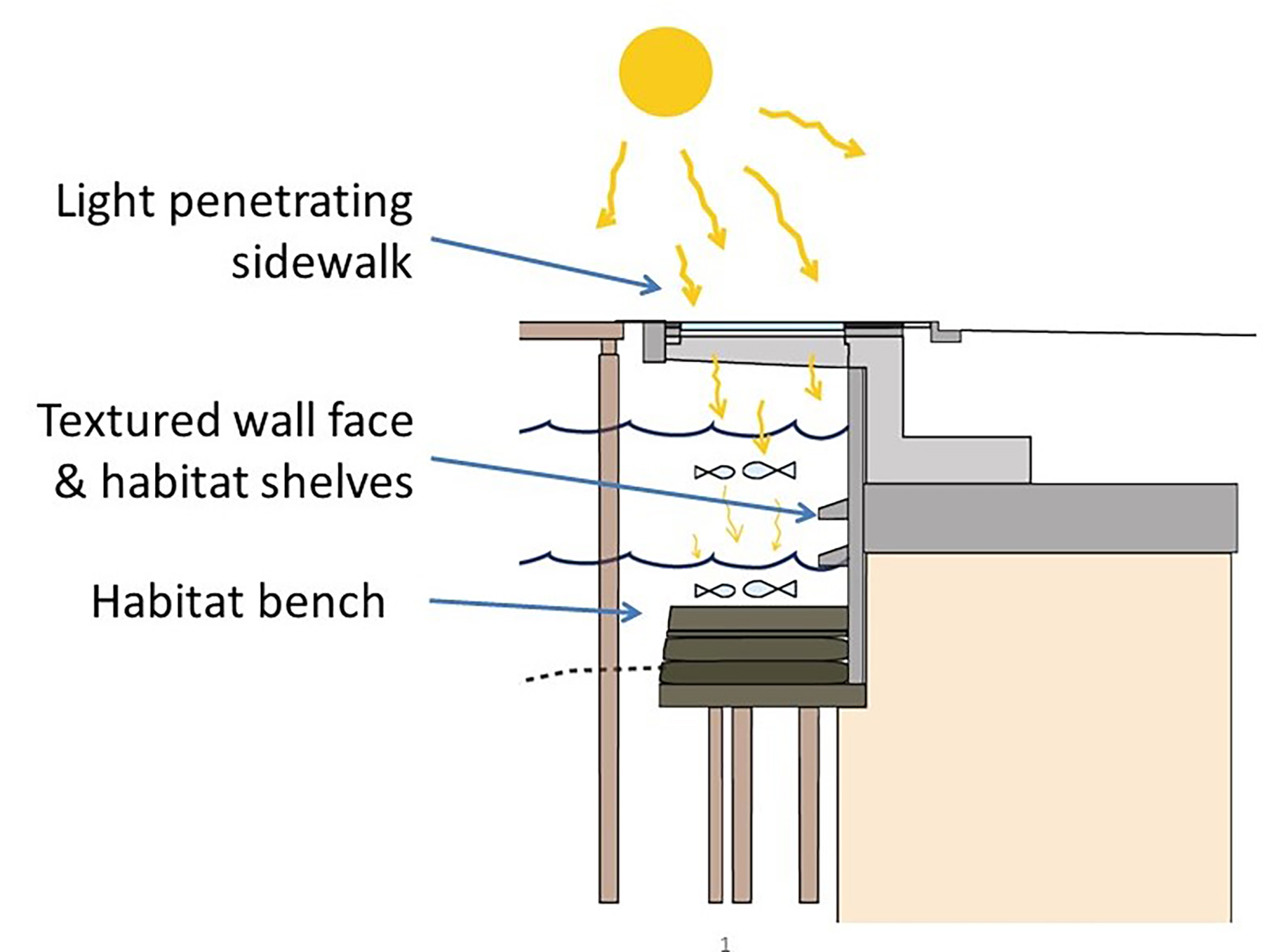

OW&CP: Habitat Beach is the gateway to the suite of continuous marine habitat improvements implemented in conjunction with the Elliott Bay Seawall Replacement Project, completed in 2017. The face of the new seawall includes grooves and nooks to promote algae growth, shallow water rock beds in the bay floor for fish to hide and forage in, and a light-penetrating surface in the sidewalk above to provide light for young salmon during their migration and to support plant life.

Habitat Beach helps reestablish some of the characteristics of natural shorelines, including shallow water, light, favorable seafloor substrates, and riparian vegetation. The intertidal beach is positioned at a critical location on the migration pathway of juvenile salmon that brings them into a shallow water corridor close to the seawall’s edge where they have opportunity to forage and rest safe from predation.

CE: What engineering firms, designers, or other consultants were involved in these efforts?

OW&CP: The city of Seattle led the Elliott Bay Seawall Project and construction of Habitat Beach. The beach design was developed by Parsons, Exeltech, Hart Crowser, Moffatt & Nichol, and Shannon & Wilson. Hart Crowser was the primary designer for Habitat Beach along with Moffatt & Nichol for coastal engineering. Shannon & Wilson did the existing condition geotechnical as well as the jet-grout design upland, while Exeltech did the seawall structural design adjacent to the beach. This team was led by prime consultant Parsons and worked in close collaboration with multidisciplinary partners due to the unique location. The city also worked closely with local Native American tribes during the design process; the Suquamish Tribe kindly donated shells for the beach.

CE: What were the major challenges in designing and constructing the project?

OW&CP: Bringing Habitat Beach from vision to reality faced many challenges. First, the location of the site was sandwiched between one of the largest ferry terminals in the country, in terms of passenger volume, and the National Historic Landmark pergola of the Washington Street Boat Landing. Moreover, in-water work was not allowed during critical periods of the year between spring and summer, so construction was restricted to just certain periods to reduce the risk of impacts to fish life at sensitive life stages.

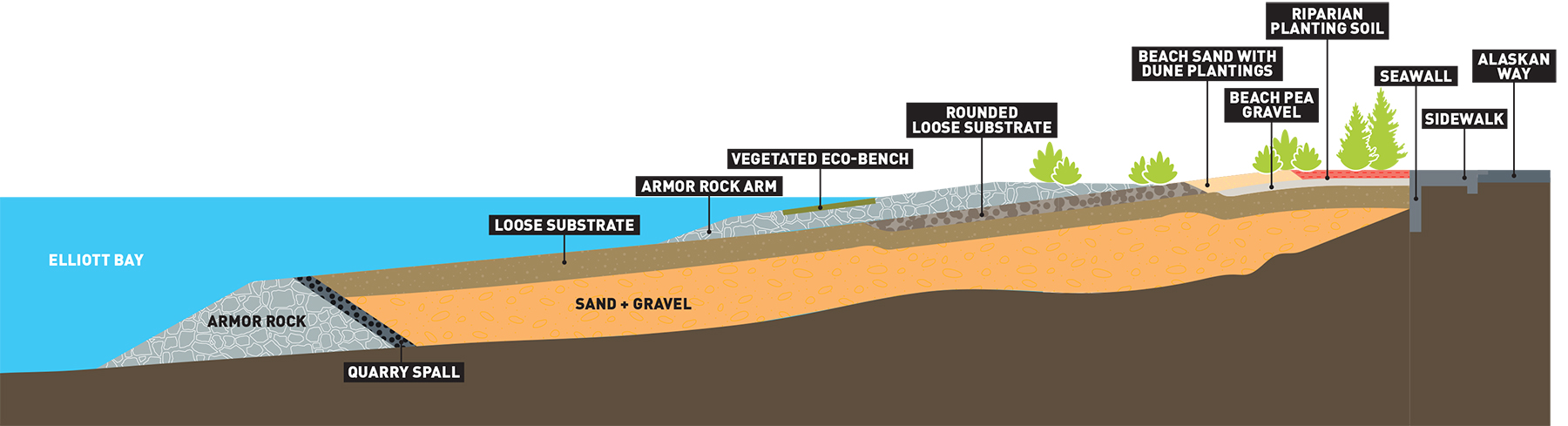

In addition, the proposed use of rock fill in the water was a concern for some regulatory agencies, primarily federal. Other groups, however, favored the habitat improvement goals of the project, including the local tribes with fishing rights in Elliott Bay. On the engineering side, it was challenging to design a small beach that filled the available space – measuring approximately 200 feet by 200 feet – but that would not get washed away, given the soft underlying soils and harsh marine environment, which features a strong tidal flux and the potential for wave action from coastal storms. Construction posed added challenges because of the need to bring in barges and marine equipment that had to accommodate the active ferry terminal and the seasonal fish migration seasons. Another example of the beach design complexity was the requirement to maintain a navigational waterway to the Washington Street Boat Landing on the southern border and not encroach on the Colman Dock ferry terminal to the north. This required the use of large, heavy boulders on the north and south sides called “rock arms” supporting a smaller substrate gradation typical of Puget Sound beaches in between.

CE: How exactly do you restore the function of a natural shoreline?

OW&CP: To make this artificial intertidal shoreline, the design team studied natural shorelines in the Puget Sound region, especially the material sizes and slopes, and then engineered the beach to mimic those. Consequently, the routes of access for visitors are narrow and meander between the plantings before opening up to a rocky beach. At each edge of the site, armoring rock arms protect smaller angular rock. In total, the new beach features more than 45,000 tons of sand (used beneath the loose substrate and armoring rock), gravel, shells, soil, and rocks in varying sizes. There are also more than 1,400 native plants, including shore pines, Oregon grapes, Nootka roses, Douglas asters, sea plantains, and other native plants.

CE: How was Habitat Beach constructed?

OW&CP: Construction began in 2018 and was completed in 2020, although the beach did not open to the public until July 2023 to allow time for the new vegetation to get established. The beach construction work included the installation of geotextile fabrics that serve as the marine habitat’s foundation system and the placement of various sizes of rock via a rock slinger and clamshell bucket.

CE: What comes next?

OW&CP: Pioneer Square Habitat Beach is one part of the overall new waterfront park system that will open in phases between now and 2025. Now that the beach is open to the public, we have received overwhelmingly positive feedback. The most frequent comment we’ve heard is that the site provides an unexpected and quiet place of respite close to the downtown bustle.

This article is published by Civil Engineering Online.